The ESA's SOPA Opera | 10 Years Ago This Month

The industry was divided on a contentious piece of US legislation, clones got bemoaned, and consoles were (as usual) completely doomed

The games industry moves pretty fast, and there's a tendency for all involved to look constantly to what's next without so much worrying about what came before. That said, even an industry so entrenched in the now can learn from its past.

So to refresh our collective memory and perhaps offer some perspective on our field's history, GamesIndustry.biz runs this monthly feature highlighting happenings in gaming from exactly a decade ago.

The Stop Online Piracy Act

From 2005 to 2011, the industry was largely unified in its lobbying efforts in the US because it was facing a serious threat from legislation aimed at curbing violent games, particular a case over a California law which went to the Supreme Court before being struck down in a decision spelling out that games qualified for free speech protections.

The victory in court was a high point for US trade body the Entertainment Software Association as far as its lobbying efforts and popularity across the industry go. After all, it wasn't like players, publishers, platform holders or any other segment of the industry wanted government restrictions on violent games. But the good vibes from that victory wouldn't last terribly long, as the ESA went from fighting government overreach to championing it in about six months. The Supreme Court ruling came in June of 2011, but by January of 2012, the ESA was publicly stumping for another piece of legislation that the various stakeholders in the industry were less unanimously enamored about.

The ESA went from fighting government overreach to championing it in about six months

The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and its counterpart Protect IP Act (PIPA) were bills in the US House of Representatives and Senate respectively that would have required service providers and search engines to block US users' access to sites (and for payment processors to not do business with them) if IP owners complain about them being used for copyright infringement, including piracy.

"Our industry needs effective remedies to address this specific problem, and we support the House and Senate proposals to achieve this objective," the ESA said at the time. "We are mindful of concerns raised about a negative impact on innovation. We look forward to working with the House and Senate, and all interested parties, to find the right balance and define useful remedies to combat wilful wrongdoers that do not impede lawful product and business model innovation."

Critics of SOPA pointed out the legislation was ripe for abuse, that rights holders could shut down sites "dedicated to theft of US property" even without a court ruling that the site is infringing on anyone's rights, and that it would compromise the DNS system. Google joined fellow tech outfits like Yahoo and Facebook in coming out against SOPA, warning that its passage would essentially mean the end of YouTube.

There were other SOPA critics as well, with hacker group Anonymous threatening Sony that it would "destroy your network" and "dismantle your phantom from the internet" when the company backed the bill. (Anonymous had also warned Sony of imminent attacks a year earlier, just weeks before a hack took the PlayStation Network offline entirely for almost a month.)

Even companies within gaming -- and members of the ESA itself -- were taking stances against the trade group and the law. After the Anonymous threat, Sony reversed course on its support; you can draw your own conclusion about correlation versus causation there. Nintendo had also initially backed the bill but recanted after criticism. EA publicly stated it never supported the bill, and Riot Games, Epic Games, Nvidia, Bungie, Trion Worlds, Runic, Jagex, and 38 Studios also came out against SOPA.

The Nvidia statement about SOPA was particularly notable as it specified that the company was not consulted by the ESA before the trade group publicly supported the bill. On the one hand, SOPA was sold as an anti-piracy bill and clearly that's always been one of the key policy positions the ESA has lobbied on, so it should have been a slam dunk to support anti-piracy efforts.

There had been enough criticism of the greater implications of the bills that the ESA should have understood its constituents might have differing takes

On the other hand, SOPA and PIPA were introduced months earlier, and there had been enough criticism of the greater implications of the bills that the ESA should have understood its constituents might have differing takes on the matter. Instead, the trade group took unilateral action on the issue and used its voice to speak against the interests of a portion of its membership.

The SOPA debate ended unceremoniously in mid-January when an official White House memo made it clear that President Barack Obama objected to the bill on grounds it would introduce cybersecurity risks without actually preventing the piracy it was intended to. While original sponsor Representative Lamar Smith said he would amend the bill in response, some of the original co-sponsors of the bill withdrew their support and the bill never actually came up for a vote.

No sooner was the bill dead than the US government reminded everyone it wasn't completely helpless in the fight against websites facilitating copyright infringement, as the FBI shut down file sharing site Megaupload, raiding ten locations and arresting Megaupload founder Kim Dotcom and a number of other executives in New Zealand. Megaupload is gone and Dotcom has spent the last decade fighting extradition from New Zealand to face charges (though a decision last month suggests he might be on the verge of losing that fight). He's also planning to start streaming on Twitch.

The ESA had shown cracks before, notably with the bizarre 2007 downsizing and relocation of E3 to Santa Monica, radically escalating membership fees to make up the lost revenue and ensuing departures of member companies.

But SOPA was the first time I recall dissent on an actual lobbying issue. Prior to this, the industry -- when it talked about legislative issues, at least -- was always on the same page. And I think that's largely because the industry was smaller, and everyone was more or less in the same boat. But with all the growth and upheaval in gaming around 2012 -- tablets, the mobile transition to free-to-play, Minecraft showing a new path to outrageous success, digital distribution clearly reshaping the console market, the rise of influencers on YouTube -- the various interests of different companies in gaming diverged like never before.

We talk a lot about the ESA's challenge in juggling the differing views from member companies on how it should handle E3, but I suspect we're going to see more friction on the lobbying side in the future as we see possible regulation around areas of the business that member companies may have different interests in -- like fights over platform holders' control over their walled gardens -- and areas that some member companies are heavily invested in while others have no interest in, like blockchain or loot boxes.

Even if the ESA can't find consensus on all those issues, let's hope it actually polls its members on what to do before publicly picking a side in those fights.

Send in the clones

Clone video games have been around almost as long as games. Computer Space took heavy inspiration from Spacewar. Pong was cribbed from the Magnavox Odyssey's Table Tennis. KC Munchkin was to Pac-Man what Fighter's History was to Street Fighter 2. More recently, PUBG is taking aim at Garena Free Fire, everyone got angry at the ersatz Wordle app, and Fortnite has been a pioneer in the fast following space, relentlessly innovating when it come to incorporating other people's innovations.

One thing many of these clone controversies have in common is that the games being copied are forerunners in exciting and often durable new genres. Pac-Man was one of the first maze chase games to hit the market. Street Fighter 2 sparked the fighting game genre, PUBG brought the battle royale concept from the modding community to the industry's main stage.

A decade ago, the simultaneous explosions of social, free-to-play, and mobile games were churning out foundational success stories with modest development budgets that reached new audiences, which turns out to be something of a perfect storm for would-be copycats, offering huge potential rewards with minimal effort and initial outlay.

For example, in January of 2012, Yeti Town developer 6waves Lolapps was accused of copying Spry Fox's successful Facebook title Triple Town and bringing it to iOS, which led to Spry Fox filing a suit over the matter. (Like many such lawsuits, it would be settled.)

Also, future PUBG maker Bluehole was neck deep in a plagiarism claim, as NCsoft sued the company that same month, claiming that former NCsoft employees had taken confidential information and artwork with them on the way out the door and were using it in the creation of the MMO Tera. (They settled that August.)

One company that was in a lot of these controversies a decade ago was Zynga. The Farmville maker was called out in January of 2012 by NimbleBit, which took exception to how closely Zynga's new mobile title Dream Heights resembled its own iOS hit Tiny Tower.

"We wanted to thank all you guys for being such big fans of our iPhone game of the year Tiny Tower," NimbleBit co-founder Ian Marsh said in a letter to Zynga dripping with sarcasm. "Good luck with your game, we are looking forward to inspiring you with our future games."

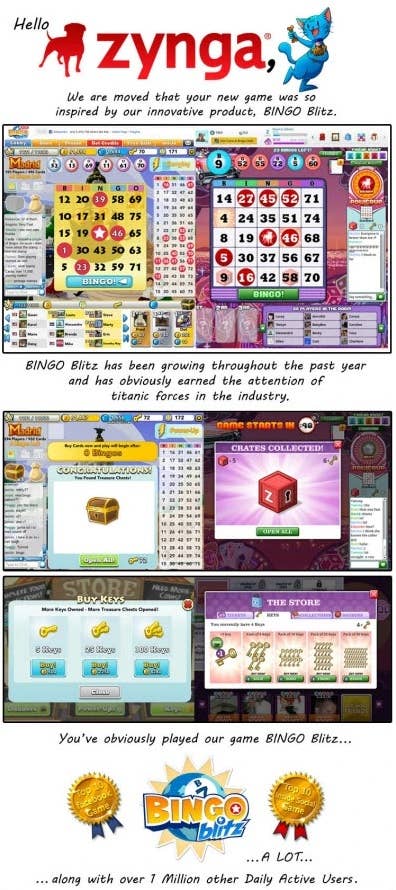

Similarly inspired by NimbleBit, Buffalo Studios then went public to address the "striking similarities" between Bingo Blitz and Zynga Bingo, which... I mean... they're both free-to-play bingo games. They're not even particularly interesting takes on bingo, nor were they revolutionary takes on monetization or presentation: as Zynga CEO Mark Pincus pointed out, both games seemed to build on conventions previously used in Zynga's own Poker Blitz.

Neither of those Zynga plagiarism disputes would end in a lawsuit, which was actually something of a rarity for the time. For example, despite Mark Pincus' apparent endorsement of fast following and iterating on what is proven to work, it had sued Playdom claiming four ex-Zynga employees it hired had taken internal documents breaking down the "secret sauce" behind successful games. (They settled.)

Zynga was aggressive about its trademarks at the time, suing the makers of PyramidVille for the use of "Ville" in the game's name, then suing the eponymous maker of casual sex app Bang With Friends over the use of "With Friends." (Zynga dropped the PyramidVille suit, and settled with Bang With Friends.)

As one might expect from a company with a reputation for cloning at the time, Zynga wasn't always on the plaintiff side of those lawsuits. The company was sued by Digital Chocolate for copying the name of its Mafia Wars mobile game and then trying to trademark it, despite assurances to the contrary. (They settled.) Zynga was also sued by The Learning Company over a FrontierVille Update called Oregon Trail. (They settled.)

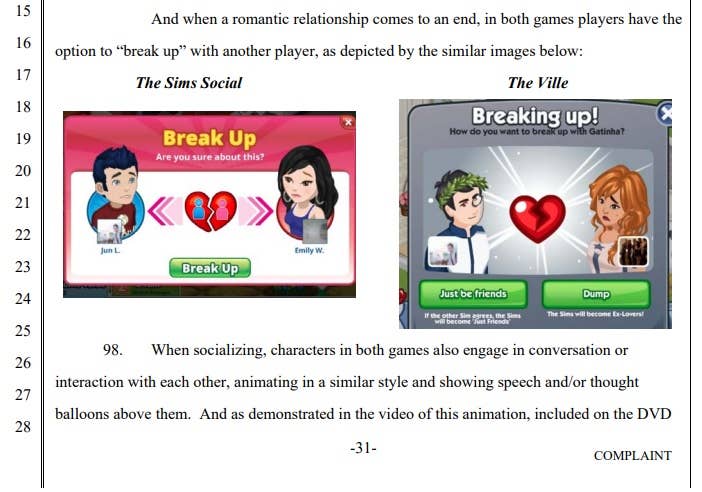

Later in 2012, Zynga would also be sued by EA, which claimed that The Ville had cloned its own recently launched Sims Social. And in one of the sloppiest or sneakily brilliant pieces of supporting evidence I've yet seen in a court filing, it even mislabelled which game was which in one of the lawsuit's screenshot comparisons.

Oh, and of course, they settled.

Good Call, Bad Call: Consoles are Doomed Edition

BAD CALL: This month's obligatory "Consoles are doomed" bad call belongs to Paradox's Fredrik Wester, who said the PS4/Xbox One/Wii U console hardware generation "will probably be the last."

HOLD MY BEER BAD CALL: Gaikai's Nanea Reeves one-upped Wester's pessimism, predicting that one of the console makers would not only drop out of the console business, but they would do so before E3 2012.

BETTER CALL: Wedbush analyst Michael Pachter served as the voice of reason, saying, "There will be another generation of consoles. There probably will be others after that. We will see migration to the cloud, but it's a migration. You're never gonna have a step function, where every game developer, every publisher says, 'Screw it. We're putting everything in the cloud, on OnLive.'"

HYPERBOLIC, BUT STILL GOOD CALL: Pachter added, "Nintendo doesn't even know there's an Internet yet so trust me, they're going to be making consoles until someone explains it to them."

BAD CALL: No hat trick for Pachter this time, as he quickly broke the streak in definitive fashion, saying "I do think OnLive thrives." Two out of three ain't bad.

GOOD-ISH CALL: "I believe the console manufacturers will stop calling them consoles on the next cycle and they'll be media devices... It's going to become confusing to a consumer." - The retiring of the "console" moniker aside, Gaikai's David Perry was right in the slightly bigger picture. Nintendo and Microsoft tried to integrate TV directly into the Wii U and "the all-in-one entertainment experience" Xbox One, respectively, and all three platform holders loaded up their systems with multimedia options and apps.

Interestingly, consumers balked at Microsoft and Nintendo's TV efforts and both companies scaled back the TV push in their follow-up consoles. For Xbox Series X|S, Microsoft ditched the HDMI-in port that let people pass their cable through the Xbox One, while the Switch is nearing its fifth anniversary and still doesn't even have a Netflix app.

I would say consumer confusion has also increased tremendously as companies roll out multiple subscription services and we see a huge array of business models, many of which are completely obfuscated until the player is immersed in them completely. (For example, People Make Games did an excellent investigative piece into the many ways Roblox can be accused of exploiting its young audience, and then had to do a follow-up when it was brought to their attention that they had missed additional questionable practices that were basically hiding in plain sight for users.)

Good Call, Bad Call

GOOD CALLS: Microsoft and Nintendo finally got around to changing some platform holder policies that seemed restrictive at the time and were downright archaic in hindsight.

Microsoft increased the Xbox Live Arcade game size limit from 150MB to 500MB and allowed games selling at the minimum 80 Microsoft Point level to be as big as 150MB rather than the previous 50MB limit. (I would mock Microsoft for thinking consumers cared about the ratio of cost-to-downloaded-file-size, but in their defense, it was common at the time for people to be furious about games shipping with DLC on the disc and being charged for a 108Kb unlock key.)

Also, Microsoft said it would phase out the awful Microsoft Points system entirely by 2013 in favor of using actual currency.

Meanwhile, Nintendo provided some helpful context for the Pachter shade above when it confirmed it was toying with the idea of maybe at some point allowing developers to sell full retail games digitally as well.

BAD CALL: The entire industry, and PopCap specifically in this instance, deciding that it's totally OK to sunset a live service game by pulling the plug and walking away from thousands and thousands of still-dedicated players who invested obscene amounts of time and money into the game. Or worse, shutting down their game and then offering them some freebies to get them into another of your live service games that will be sunset a few years down the road.

CREEPY GOOD CALL: Gamigo co-CEO Patrick Streppel wasn't worried about optics when discussing traditional developers having problems with free-to-play, saying, "They are focused on making a fun game -- of course fun is important for free-to-play -- but they are not focused on how to design the game so it gets challenging enough to get 5% of users spending money, and how to design the game so that it is possible, in theory, to spend an unlimited amount of money. Most games are really designed so people can spend $100. I say, 'No, no, no, people should be able to spend $10,000, $100,000 into this game.'"

WELL-REASONED (BUT ULTIMATELY BAD) CALL: Sterne Agee analyst Arvind Bhatia crunched the numbers on Zynga's user growth, the marketing money spent to gain those users and their expected lifetime value, and concluded that Zynga was losing $150 on every new paying customer it acquires, adding, "That math won't work for very long."

Turns out that math might be able to work for at least a decade. Zynga spent $710 million in sales and marketing over the first nine months of 2021 and increased its mobile monthly active users by 49 million. Last year Zynga said roughly 3.4% of monthly active users actually paid, so we can assume that addition of 49 million monthly active users yielded 1.67 million people who actually paid money, or about $426 per paying user.

Zynga doesn't seem to report average lifetime value of a user anywhere, but Bhatia put the figure at about $150 per paying user a decade ago. There are a few places Bhatia's back-of-the-napkin math is debatable -- NaturalMotion CEO (and future Zynga employee) Torsten Reil's own estimates put Zynga as gaining $30 per paying user rather than losing $150 -- but it also might help explain why Zynga has lost a lot of money in the past decade.

Losses aside, Zynga also kept the lights on and revenues growing long enough to attract a massive acquisition deal from Take-Two, so the math seems to have worked out for as long as Zynga needed it to. It will certainly be interesting to see where it goes from here, though.

CALL PENDING: Sometimes a decade just isn't a long enough time frame to conclusively determine whether someone was right or wrong about something. For example, in January of 2012, GSC Game World was "hopeful" that things would turn out well and it could finish Stalker 2. Since then, the company collapsed, returned almost three years later, and finally announced an April 2022 release date for the long-awaited game.

Earlier this month, GSC Game World delayed Stalker 2 to December 8, 2022, saying, "We are convinced development should take as long as necessary," as if anyone was worried this thing announced a dozen years ago was in danger of being rushed out the door.