What's wrong with the games industry, and how to fix it

At Devcom, Kate Edwards highlighted the main issues affecting game creators, and what the industry can do to address them

Unexpected closures, layoffs even as companies report record profit, crunch, sexism, racism, online harassment: the games industry doesn't lack reasons for its members to experience mental health issues.

In the US, one out of five people are diagnosed with some mental health condition every year. And one in two people will be diagnosed with a mental health issue at some point in their life.

In its "State of the Industry 2019: Mental Health in the Game Industry" paper published in July 2019, non-profit organisation Take This examined the particular set of factors that make games industry employees particularly at risk of mental health issues. In a Devcom talk earlier this month, executive director of Global Game Jam and Geogrify CEO Kate Edwards explored these key factors in depth.

"One common theme that is concerning to [all developers] is the issue of mental health"

"In the time that I've been in the industry -- and I've spent a lot of time in this industry -- I've had the opportunity to travel all around the world, talk to developers of all kinds from solo indies in a garage, to large AAA companies with tons of developers," Edwards said. "And one thing that has constantly come through as a common theme that is concerning to them is the issue of mental health.

"It comes up time and time again. Issues of crunch, sexism, work-life balance. Even the stories [about these issues] cause a certain level of stress when we're working in an industry like this, which is under a lot of dynamic change. There is a cost to this. And that cost is the mental health of the people doing the work, which is all of us. And so that's why I want to talk about mental health and how it affects game creation."

Using the Take This report as a starting point, Edwards explored each of the key factors affecting the mental health of game creators and offered ways to address them:

Issue no.1: Lack of job stability and longevity

- The reality

The games industry is known for its constant shifts, with companies regularly changing hands for instance, which can be extremely disruptive. In the past couple of months only, Take-Two acquired mobile developer Playdots, TinyBuild purchased Hello Neighbor devs Dynamic Pixels, and Embracer Group bought multiple studios, including 4A Games.

But the games industry also suffers from regular, sudden studio closures. This year, DayZ creator Bohemia Interactive closed its development studio in Bratislava, Ultimatum Games shut down, HQ Trivia ended, and Nexon OC closed. And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

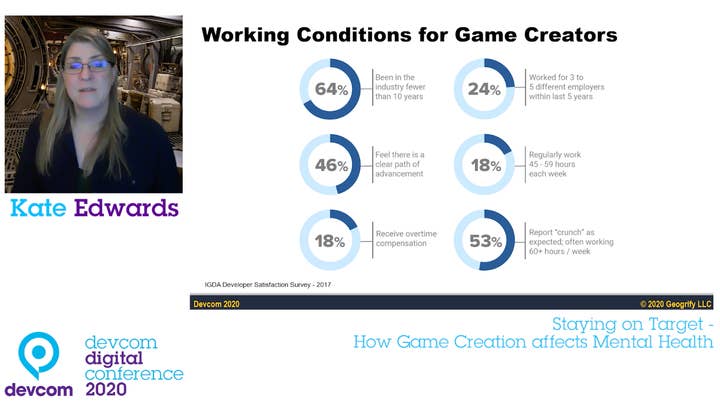

"24% of people in the industry reported that they've worked for three to five employers in the last five years"

The lack of job stability and longevity has been a known issue in the games industry for almost as long as it has existed. Interestingly though, in the IGDA's Developer Satisfaction Survey from 2014 that Edwards quoted in her talk, 61% of the respondents saw themselves staying in the industry "indefinitely," showing the dedication and passion of game creators despite working in a volatile environment.

"They want to be in that industry basically for the rest of their lives," Edwards commented. "And that's very consistent with other people in creative media. A creative spirit is not something that retires, it's something that continues on and on. So you have these people who are incredibly passionate and they want to be doing this forever.

"[But] 24% of people in the industry [in 2017] reported that they've worked for three to five different employers in the last five years. That's a lot of disruption, that's a lot of moving around, that's a lot of job changes, and so that can add a tremendous amount of stress."

Looking at the most recent IGDA Developer Satisfaction Survey from 2019, that number actually jumped to 28%. In addition, 42% of the respondents said that crunch time was expected at their workplace.

Edwards summed up the common stress points related to working conditions:

- Having to crunch, or suffering from time pressures even if your company doesn't crunch

- Uncertainty around job stability, which worsens if you're in a competitive workplace

- Frequent job location changes

Edwards dedicated an entire segment of her talk to crunch specifically, and how it fuels burnout, emotional exhaustion, feelings of hopelessness, and reduces personal accomplishment.

"The industry is slowly starting to mature, but there's still a lot of ways we can go to improve [crunch] very quickly," she said. "But it's not a surprise then that when we ask people reasons for wanting to leave the game industry, the number one answer is that people want a better quality of life."

To learn more about crunch specifically, and its impact, Edwards recommended reading "The Game Outcomes Project" (2014), as well as a white paper from Take This called "Crunch Hurts," published in 2016.

- The solutions

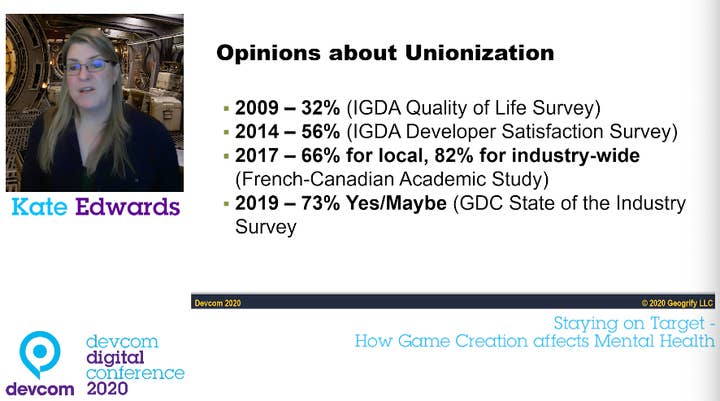

One of the ways developers can challenge job instability and over time is unionisation, Edwards pointed out.

"I realise this is a somewhat controversial topic, but we can see here [see below] from different survey results over the last few years that the support for the idea of unionisation has actually increased pretty significantly.

"Now does that mean a union is going to solve all these problems? Not necessarily. But what is being said here by a lot of developers is that they want some way of controlling these factors. They want a way to control their work-life balance and to make sure that they're not overworked, that they can control the certain levels of stress that they have to deal with -- and they see a union as being one of those mechanisms that might be able to help them do that.

"It's no surprise to me that the support has increased over the last decade or so, because we haven't seen a tremendous amount of change in some companies. There's been small incremental changes though, and there's been a much louder call to address the issues in the industry."

"[Developers] want a way to control their work-life balance -- and they see unions as mechanisms that might be able to help them do that"

In order to tackle working conditions in the games industry, Edwards believed that better training for managers is also essential.

"Leadership training for managers [to help] them understand the importance of mental health awareness, and the impact on the workers, [is important]," she said. "But also support for change management and studio upheaval, because it is something that a lot of us experience. Having to shift a job all the sudden, or a game project canceled or extended: there is a tendency to be a lot of churn in this industry and companies need to be better prepared for it."

The games industry also needs policies to support "portability," meaning the ability for staff to be more mobile in their jobs, Edwards said. However, this aspect is on a positive path due to remote working having been so prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Maybe the mobility issue won't be as much of a factor now that we're seeing more and more companies embrace remote working because they realise that, not only can it work, [but it also] minimises the amount of disruption going with having to move around."

Concerning crunch specifically, managers need to realise that the work-life balance of their employees is instrumental to the studio's success.

"Your talent is the number one resource you have, it's not the money that you have in the bank"

"Oftentimes [when] people complain about crunch of their workplace, they're told by a manager something like: 'You're lucky to work in the game industry, what are you complaining about?'," Edwards explained. "That's obviously an inappropriate response. If you're in a management role and you're hearing people complain about the amount of work [they have], you need to listen to that.

"Your talent is the number one resource you have, it's not the money that you have in the bank, and it's not the IP that you're sitting on. It's the talent who is working for you, they're the ones that you need to care for the most."

Issue no.2: Lack of diversity and inclusion

- The reality

The games industry is notoriously lacking diversity and inclusion, and there are stories every single day highlighting cases of racism or sexism. While things are improving, this process is painfully slow, and the recent UKIE census pointed to a UK industry that is still overwhelmingly young, white, and male.

"Some people might wonder: why would this affect people's mental health?," Edwards said. "[But] if you are in a company [and] you're not seeing people like you, that can cause stress. Or if you're not seeing games being created for a more diverse audience, that can also cause a certain amount of stress.

"So when we ask in the [2014 IGDA] survey, 'Do you feel there's equal opportunity and treatment for all in the game industry', the resounding answer [is] no. And that should be concerning to all of us."

"If you are in a company [and] you're not seeing people like you, that can cause stress"

Edwards pointed out that roughly 22% of people working in games worldwide are women. In terms of ethnic diversity, the 2019 IGDA survey showed that only 2% of the respondents identified as Black/African-American/African/Afro-Caribbean, and 7% as Hispanic/Latinx.

"What's interesting though is when we asked developers 'How important do you think diversity is', 75% of the respondents think it's very important or somewhat important.

"So there's obviously an interest in having more diversity, yet we're not at that state yet. In the United States, for example, 41% of game players are women according to the latest stats from the ESA, whereas only around 24% of game developers are women. So we basically need to do a better job of making games for everybody who plays games, not just who we think plays games."

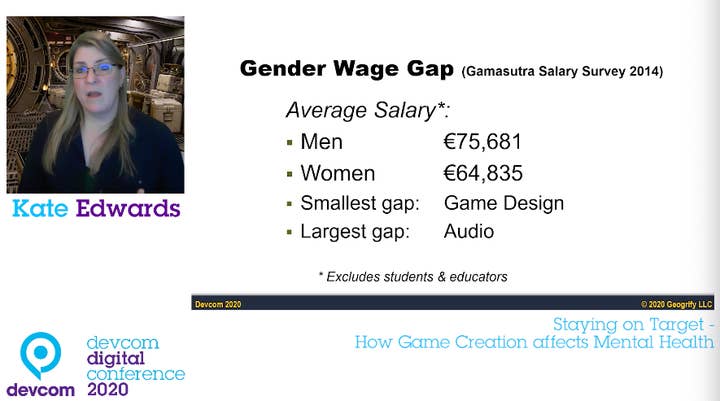

Edwards also presented some figures demonstrating the differences in salary depending on gender in the industry (see below).

"I grant you this data is old [2014], but there hasn't been a really good comprehensive salary survey since. But the wage gap between gender is pretty significant. That's a very concerning thing as well."

Unfortunately, the wage gap between men and women also still very much exists -- and it even widened in the UK in 2019.

Then looking at a report published in 2017 by Kapor Center and Harris Poll, called the Tech Leavers Study, Edwards highlighted that there's a general sense of unfairness perceived by people from underrepresented backgrounds.

"Unfairness costs a lot of money, because you're losing talent, you're having people who leave jobs and going elsewhere," she said. "Diversity and inclusion initiatives can really improve culture and reduce turnover, but only if they're done well."

- The solutions

There are many ways to improve the sense of inclusion in the games industry.

"Our goal with inclusion is we want those who create games to better represent those who play them," Edwards said. "We know that people who play games today are basically from every walk of life and every kind of demographic. A lot of people don't even realise that there are more 40-years-old women who play video games than teen males.

"We need to do a better job of making games for everybody who plays games, not just who we think plays games"

"So what we need to try and do is maximize the global reach of our games by considering the expectations of a much broader demographic. To better anticipate what those expectations are, we need to have companies that are more diverse and have people from different backgrounds."

She gave the example of US-based TV network FX, which found out during its 2014-2015 season that only 12% of its show directors were women or people from underrepresented backgrounds.

"And so the CEO made a very conscious decision that this needed to change," Edwards explained. "Two years later, 51% of their directors were women or underrepresented people.

"Basically [CEO John Landgraf] recognised that they were working in a system that was biased and that he wasn't taking responsibility. So he just decided as the CEO: we're going to change this. And he made that happen. And really that's all it takes. It's a matter of will, making a decision that this is going to be important to us, and we're going to make this a priority. And we need to see more of that in the games industry."

There are other ways to address and improve diversity and inclusion, she continued. For instance, inclusion needs to be implemented as a modus operandi at games companies.

"Bias that exists within the company has to be exposed, it has to be brought to the attention of leadership. There should be a whistleblowing or accountability mechanism.

"We also have to look at recruiting practices, how we reach out to people, what our job descriptions sound like. When we use language like 'we're looking for a hot shot' or a 'rock star' that tends to be gender-biased language that maybe guys respond to, but women tend to not respond to that as well. So even though they might be fully qualified for the job, they might see language like that and say: I'm not going to try and get this job."

"Bias that exists within the company has to be exposed, brought to the attention of leadership"

In terms of the games being created, developers need to ask themselves: who's our target audience? Are we making this game for who we think we're making it for? Are we trying to make this for the broadest possible, multicultural audience out there?

"The broader that you can think about who your audience might be, the more appeal this game might have," Edwards said. "Of course, you always need to stick to your creative vision, but it doesn't hurt to think about how that creative vision is gonna be perceived by different groups, cultures and demographics around the world."

Issue no.3: The public perception of games

- The reality

The final point Edwards addressed in her talk is the public perception of games. That includes common occurrences of games being linked to mass shootings and gun violence.

"We hear these stories all the time -- the current government in the US has been very open about complaining about video games. And when I see things like this, what I see is a failure of the industry to step up and do its job, which is basically to defend itself as a creative medium.

"Within another ten or 15 years, every single politician on earth will have grown up with video games, and so I do think there's going to be a perceptual shift that's going to be really healthy for the industry. Some punctuated events like the pandemic have actually been a factor in helping the broader public understand that games can play a really healthy role as a form of entertainment, and you don't have to fear them as a medium."

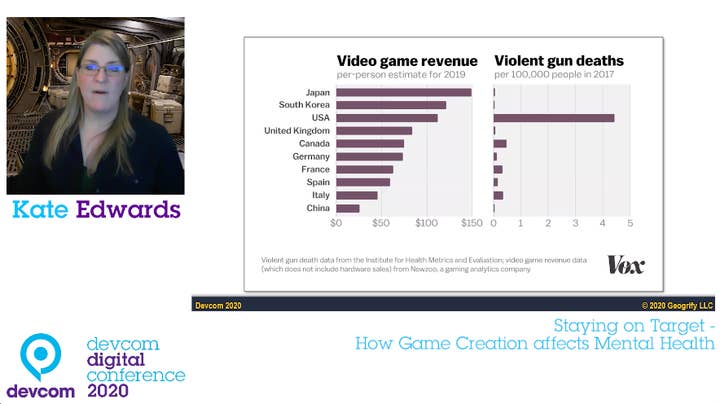

Edwards shared a chart putting violent gun deaths in perspective with video game revenue in several countries (see below), making it clear that the problem is not the games.

"But getting people to listen to a rational empirical argument is not easy," she added. "My point bringing all of this up is not necessarily to have a debate about violence in video games. The point is that as games creators, this adds stress to our lives, having our profession judged in this way on a constant basis."

The public perception of games can wear staff down, especially those in community-facing roles. And that also includes issues other than violence, such as the idea that games are played only by kids, that they're a waste of time, or that game developers are lazy or only motivated by money.

"These are misperceptions, but they are still persistent out there in the public, even though in the United States in 2011, we had the supreme court rule that there's no link between violent games and its effects on children.

"Just a few years later the Pew Research Center did a study and found that 40% of adults still believe that there's a relationship between games and violence. 26% think that games are a waste of time, 60% believe that games are played mostly by men, and that 23% think that games don't promote teamwork and communication. So that perception lingers and it's really stressful and troubling."

- The solutions

In order to improve the public perception of games, the industry needs to embrace the cultural significance of the medium, Edwards said.

"We need to embrace the fact we're not some small startup industry. We are a strong, powerful, cultural and economic force"

"Essentially, games represent the current evolution of human narrative. So we are defining how stories get passed from one generation to another. And our stories are on a platform that happens to be very interactive. Games have become an empathy engine in ways that film and other forms of creative media have not been able to achieve. And I think we need to embrace this. This is a really important task that we're doing."

Embracing the economic power of games is the second part of that equation, she continued.

"I think most of us understand this part already. Video games make more money than film, and music, and books, and a lot of other forms of entertainment out there. What's really crazy is that if you take all forms of live sports around the world, we still make more money than [that], which is a crazy staggering amount of money.

"I'm not saying we have to basically flaunt that and be proud of it, but we need to embrace the fact we're not some small startup industry. We are a real, strong, powerful, cultural and economic force on this planet right now. I think the pandemic has shown that people have embraced games as a way to cope and as a form of entertainment."

What sometimes sets games apart compared to other forms of entertainment is that most people do not understand how they're being made. Making that process more transparent could help improve the public opinion, Edwards believed.

"We can all strive to make some kind of difference by being more vocal about what we do"

"We need to open up the black box of game creation. This also would help give us that confidence, and boost [to] the mental space that we live in as game developers, to help people understand what we do.

"The non-playing public have been the most vocal against video games, even though they're in the minority in terms of the total population. And so I think we have a responsibility as game creators to do more to actually interface with the public and get them to help us with our message.

"We should not just sit back and expect it to happen. There's a lot that we can do as game creators. For example, you could open up your studio and have an open house, or invite politicians to come and actually show them exactly what you do. They'd found out that these are really cool people, and they also happen to be local taxpayers."

Speaking to the press or writing opinion pieces are also things studios should do more of, Edwards continued. And that means outside of the games press, where non-gaming people will actually see it.

"The fact is, as a game creator, your goal is not to really convince the entire world. All I'm encouraging people to do is try and change their small corner of it. We can all strive to make some kind of difference by being more vocal about what we do. And as we are vocal about our job we also find that confidence which I often have found has boosted people's sense of mental wellness, this sense of satisfaction in the work that they do rather than being judged for it.

"I think if we're all doing this together, we can actually make a lot of change happen on a global scale."

If you want to read more about these topics, head to the GamesIndustry.biz Academy, where you will find guides dedicated to approaching mental health issues in the workplace, identifying and avoiding unconscious bias, avoiding burnout, and more.