Worlds-as-a-service: Charting the future of location-based games

Mantle CEO Dean Gifford on why his team can finally build the tech that will take geo-location game design from Pokémon Go to GTA Worldwide

Prior to 2016 location-based games were, to say the least, very niche. Beyond Ingress, Shadow Cities and a handful of other ambitious but largely overlooked titles, there were few companies trying to combine real-world data with mobile gaming. Then Pokémon Go happened.

There's little point in discussing the wider impact of Niantic's second outing - the monster-catching title has generated countless headlines and thinkpieces from both within the games industry and beyond since its launch this summer. But for one company the influence of Pokémon Go was invaluable, largely because it validated everything the team had been working on for the last four years.

London-based developer Preliminal and its newly-founded offshoot Mantle Technologies first emerged in 2012, entering various developer and innovation competitions to help raise funds and gather support for its dream project: Fractured Skyline, a turn-based strategy affair where the cyberpunk game world is generated from the real one.

The project is still in development, partly while Preliminal mastered the technology that could take street data and more to create the world around the user, but pitching this to interested parties has become much easier since the arrival of Pokémon Go.

"For the longest time, explaining to anyone why a geo-location game is interesting or useful took easily half the time that we were explaining what we were doing," CEO Dean Gifford tells GamesIndustry.biz. "Pokémon Go has given us a shorthand for the concept and exposed it to a much wider audience. It's become possible to be a market by itself - we don't have to explain that any more.

"Niantic has been able to make all the mistakes and deal with all the expensive fallout of people being silly with a new medium and working it all out - which we panicked about for the longest time. It has survived mums and dads, and everyone getting in and having a play with it."

Gifford commends Niantic for its accomplishments, but observes that for all the furore around Pokémon Go, the game is mechanically very simple and has set the bar low for future geo-location games. It's something his team plans to take further. A lot further.

"At the moment, people are just collecting things," he says. "What would that be like if you were fighting over actual terrain? It's been interesting to see them kind of plow a furrow, for us to watch what they've done and then capitalise on those mistakes. We've been able to look back at the design we had and make changes or know we were on the right track. It's all worked out quite well."

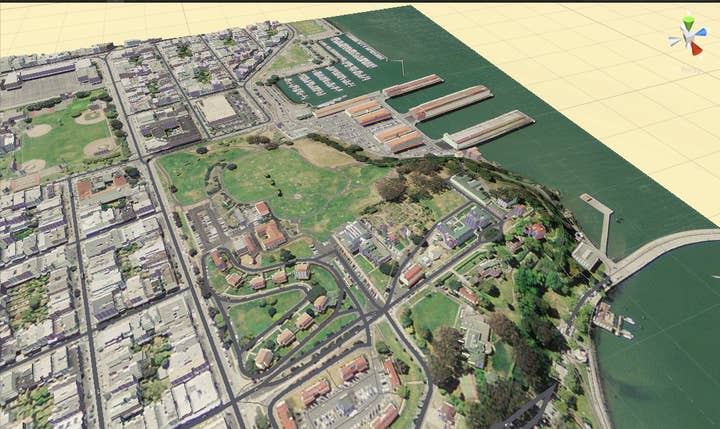

Fractured Skyline is essentially on hold, however, while Gifford's team not only perfect the technology but sell it to other developers as well. The Mantle engine generates a 3D game world based on location data from the user's position; not just the street layout, but other transport networks such as railways and even (if available) the height of nearby buildings.

Meeting Gifford in London, I saw a demonstration of the tech on his smartphone. Within less than a minute, a 3D game world had been created and populated with a steady flow of road traffic. The placeholder hero could be controlled similar to any third-person action game and I was able to explore the surrounding streets, instantly recognising the layout of the areas available as those around our meeting place.

"Niantic has been able to make all the mistakes and deal with all the expensive fallout of people being silly with a new medium and working it all out - which we panicked about for the longest time."

Dean Gifford, Mantle

When asked why Mantle Technologies, established earlier this year, would focus on sharing this technology rather than using it in its own titles, Gifford says the team always planned to make it available as a tool at some point in the future.

"We just didn't feel that we had the resources to do both at the same time, or that the game was going to make us enough money to continue building the engine afterwards," he explains. "We thought building the engine was going to be a bit more reliable as an income stream so we could then go back and build the game.

"We're still trying to get the engine out and stable, and looking at ways we can sponsor and fund Fractured Skyline until its finished. But the engine is really timely because people are trying to make Pokémon Go clones as fast as they possible can."

While the tech is impressive, Gifford stresses that it should only be used as the foundation for a game. As he mentioned earlier, Pokémon Go's mechanics were simple enough to capture mainstream interest and were, importantly, well designed - out of necessity, he argues, given that without them the game is just a colourful 2D map. Developers using Mantle need to think about their own mechanics if they want their location-based games to stand out.

"As we've seen with No Man's Sky, you can't just rely on an engine being all-singing, all-dancing and hope for the best - you have to have really good gameplay in there as well," says Gifford. "What I like is that with Mantle, we can give people the opportunity to have an engine that does a low-level of pretty awesome stuff right away and you start your development cycle by building mechanics. You can pour more effort into the more needed and interesting part of the game, which is the gameplay itself."

Long before Pokémon Go, developers have tried to build compelling location-based games, particularly since the widespread adoption of the smartphone and its position-tracking capabilities. It may have taken the recognisable IP of Pokémon to attract the masses, but Gifford is confident such games were always going to be popular as more people discovered them.

"People always have a really interesting reaction to location," he says. "When they see our demo, they're like 'oh, that's actually where I am', they start thinking about where they work, where they live, how they get there. They immediately want to explore.

"People now have the bug, I think they understand why this is an interesting thing, that there might be cool things for them to explore, easter eggs to pick up and new ways to enjoy the real world. And that's become a mainstream understanding, which is what we'd always hoped. It's just nice that we haven't had to break through that market by ourselves, which would have been fairly difficult."

"The vision for Mantle is worlds-as-a-service. [I want to see devs build] GTA Worldwide, where you can generate the environment and run around in it."

Dean Gifford, Mantle

Given the 3D nature of Mantle's game worlds, it's easy to imagine what sort of titles could be built with Gifford's technology: local versions of Grand Theft Auto, Watch Dogs or Driver, or perhaps Shenmue-style RPGs. While the demo I was shown transformed London into a cartoony metropolis, Fractured Skyline is using the tech to depict a cyberpunk vision of your location's future, and it wouldn't be difficult to render post-civilisation ruins in the style of The Last of Us.

All these projects unquestionably appeal to a core audience, albeit through a mainstream platform in the smartphone, but the team is confident Mantle could be used for a much wider spread of games.

The flexibility of Mantle means that you can style it however you want," says Gifford. "You can use it as for a 2D game, you can use it as a 2.5D system where everything's flat with very small buildings as indicative [of your location].

"This demo is what we refer to as a factual styling: we've taken the actual data and just reskinned it. We've also got the ability to use the underlying mapping content as a seed to generate procedural content. You could take a whole bunch of models and other content and use only the street information to place that content, which then gives you a different way to experience that. That could be a 2D experience as well, or an isometric one where it's less claustrophobic."

The idea of visually overhauling the world around the player will be particularly powerful in cities, which, Gifford observes, is where many consumers live or at least have access to: "We have a psychological understanding of how cities work, what they do, how they should look, what their different spaces mean. When you take that understanding and start to play around with it, you start to reflect on those things: what does a park look like in here? What does my park look like?"

Gifford even hopes to see the Mantle engine used in virtual reality titles, adding that his team have even built a version of the demo I was shown for Gear VR.

"I couldn't say exactly what a VR experience with Mantle would be," he says. "I'm hardly going to go to a park, put on my GearVR and then experience it. But the idea you could be at home, or somewhere comfortable with a GearVR and experience a geo-located area around you... There is totally scope for VR content. I really couldn't give you an exact use case but it's something we're going to be playing with."

Mantle Technologies is even speaking to HoloLens developers to see if there are mechanics of functionality they can stitch on top of the engine's real-world environments. It has also begun attracting attention from outside the games industry. One theme park has been speaking to Gifford and his team about creating something that would allow visitors to experience a new take on their environment, either while queuing for rides or looking around the park for places to go.

In the near future, the Mantle engine will be expanded with new forms of data that will help bring more detail into game worlds or create more varied environments. Planned additions include 3D terrain that takes hills and mountains into account, satellite overlays, and more. And while the tech is currently built on Unity, the team hopes to bring it to Unreal and other engines, as well as browser-based WebGL engines such as PlayCanvas.

"The vision for it is worlds-as-a-service," explains Gifford.

He finishes our discussion by hinting at a new use-case he has only recently envisaged, one that might be a good fit for Mantle and VR. The CEO was surprised to discover that some groups broadcast their Dungeons & Dragons sessions via Twitch, which got him thinking about people still playing more traditional forms of RPG but in new and modern ways.

"If you had networked VR linking players together," he says, "if you could have a world they inhabit where they're playing like a Neverwinter Nights game, but based on their area, and the DM places content down around you - how fantastic would that be?

"That's my new vision. My vision for the longest time had been GTA Worldwide, where you can generate the environment and run around in it. Those are the two things we're trying to do."