The Price of Fame

Superdata's Joost van Dreunen examines the impact YouTubers, Hollywood celebrities, and big-name developers are having on the industry

During a recent conference, I ended up holding the hotel elevator for what I thought was a couple on vacation. As they entered, they shouted to someone in the lobby: "No, we're YouTubers. We're kind of famous. You should check us out online." Later that week at a party organized by the community manager of a big Asian MMO company, I noticed a group of gamers asking one of the other attendees for an autograph. Not knowing the person, I asked someone and was told: "Yeah, he's a well-known German YouTuber."

Celebrity will kill the video game star.

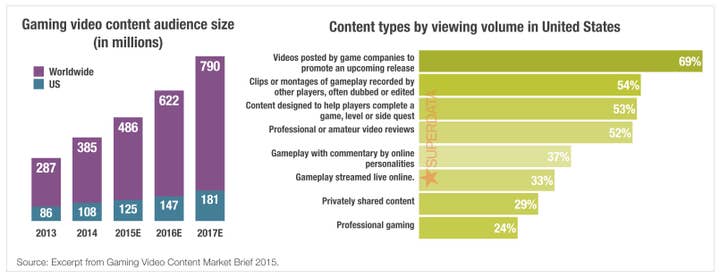

By now PewDiePie is a household name among many of us in the industry. Here's a guy with a knack for witty commentary and an ability to speak as an authentic human. He, above all others, managed to connect with a growing audience for gaming video content. As one of the most popular channels on YouTube and Twitch, gaming-related videos are on track to generate $3.8 billion this year alone, catering to an audience of 483 million people.

Think of it as a layer on top of the actual game play: Rather than playing the games, people will watch others play. According to some observers, "watching games will soon be more popular than playing them." And the data confirms it. But the growing abundance of YouTubers and other aspiring celebrities that seek to make a living by providing commentary and witty banter around game video is also a sign that the games industry is changing.

The question is whether it's a good thing.

Red carpet games event.

Years ago I had a guest speaker from Rockstar Games in my class who pointed out that, different from the film industry, there was no 'celebrity culture' in the games industry. He argued that most people don't buy a game because a particular developer worked on it. To paraphrase him, "There is no award ceremony for the guy who programmed the chopper in GTA." However, stars like Brad Pitt and Meryl Streep can bring a lot of people to the cinema on name recognition alone. Consequently, people like them are honored every year in a series of award shows that help both raise their profile and provide the film industry with a cultural gravitas. It serves to remind us of how important the film industry is.

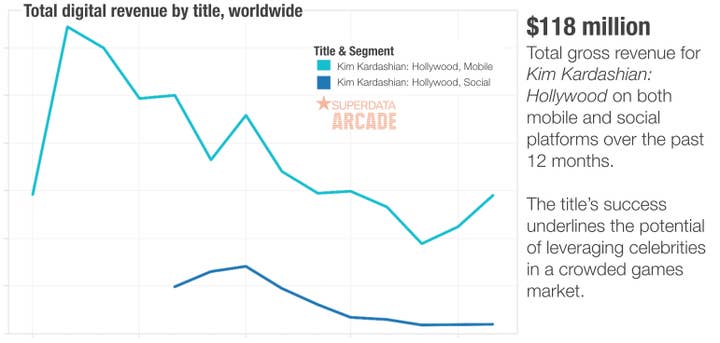

For a long time we've been telling people that games ($25B in 2015E, United States) are now bigger than movies ($11B at the box office). And now celebrities are answering the call. For someone like Kevin Spacey, who was a voice actor in Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare or Kate Upton, a model that starred in a TV commercial for Game of War, it is just another job. For others, it's more lucrative. During an earnings call, Glu Mobile's CEO was asked what it was like to work with an A-lister like Kim Kardashian. "Isn't she difficult to get a hold of?" asked a financial analyst. The CEO simply replied, "No. Because after her reality show, Kim Kardashian: Hollywood is her second biggest revenue stream."

It works both ways, of course. Electronic Arts knows this all too well and for years has featured famous NFL players on the cover of its boxes. In the increasingly crowded mobile games market, celebrity has proven to be a great way to reduce user acquisition costs and keep, especially free-to-play games, on the top of people's minds. Glu Mobile recently posted stellar figures, not in the least thanks to its persistent and successful use of well-known people, musicians, and Hollywood plumage. So while there still may not be a celebrity culture among programmers and developers on the same level as the film business, it looks like this is about to change.

More like "crowdedfunding."

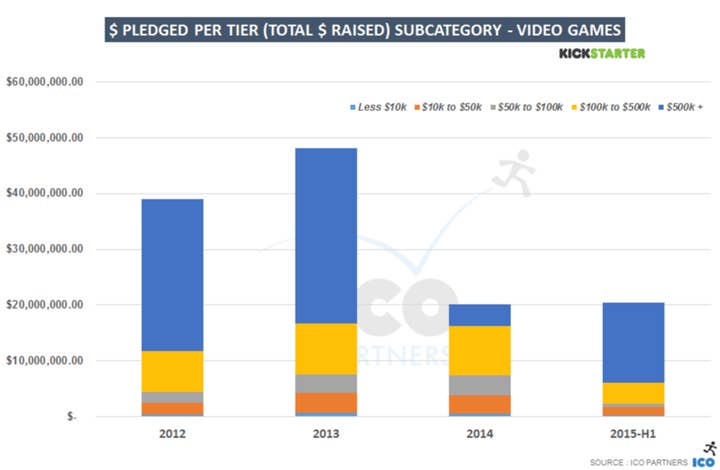

On the creative side, too, there's a noticeable move towards celebrity culture. It makes sense, of course, to invest in people who have a proven track record. Especially in a hit-driven industry, it is practically a no-brainer when trying to mitigate the risk that comes with the massive but necessary capital investment. It doesn't always work out well, it seems. To do well on Kickstarter and raise a bunch of money it really helps if you've worked on a game in the past that did well. It crowds out newcomers who, in the absence of notoriety, have a more difficult time seeing their projects materialize. According to Thomas Bidaux at ICO Partners, "The majority of the money raised by video games was through very large projects. If the current trend continues, projects that raised less than $500,000 are on track to garner less money than in 2014." In a follow-up email conversation, he added that it is in particular a combination of "celebrity designers with a wide public appeal...[and] the closer to their game of fame, the better."

High-flyers on Kickstarter can raise a lot of money, like Shroud of the Avatar by Richard Garriott ($1.9 million), Shenmue 3 by Yu Suzuki ($6.3 million) and Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night by Koji Igarashi ($5.5 million). As an increasingly top-heavy layer of celebrity talent monopolizes investment money, without providing a consistent output of new innovative experiences, it fundamentally undermines the model of crowdfunding and makes it even more difficult for small fry outfits to raise capital.

Collectively, all these aspiring YouTubers, cross-media celebrities and famous designers are adding a new content category to the games industry. I'm not advocating some utopian purist game industry, void from the very forces that inform every other cultural industry. Games are necessarily and irrevocably the product of a much more complex intercourse of ideas, beliefs, commercial principles, and market forces.

But now that games have entered the mainstream, they are bound to change. As fame and celebrity latch onto the games industry as it moves upward, it begs the question of if and how it will affect the industry. Will it help accelerate its creative effort and inspire new innovative experiences? Or will this drag it down to a base level form of entertainment? (Is that even possible?) And even if that happens, isn't that the price an art form must pay to reach mass adoption and allow designers to share their ideas with a larger audience?