Kicking and Screaming: Leaks, Day 1 patches, and No Man's Sky

Are Hello Games' pre-launch woes evidence of a console industry struggling to come to terms with its digital future?

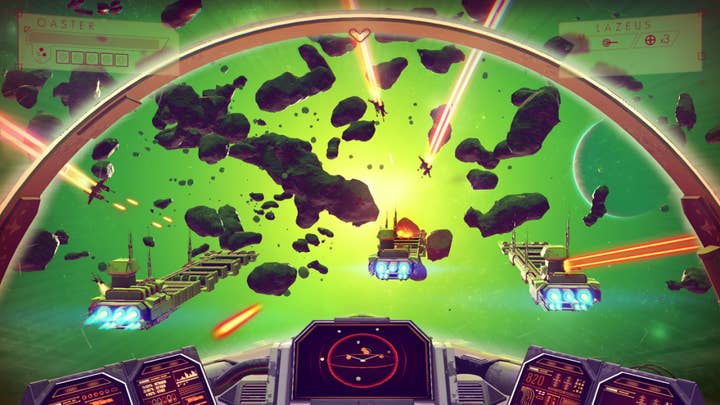

When Sean Murray thought ahead to the days and weeks leading up to the launch of No Man's Sky, he may well have imagined a very different scenario to the one that exists today. Hello Games' third project as a studio went from relative obscurity to become one of the most anticipated games of recent years, largely down to a handful of knockout showings at major public events and the sheer ambition of what this small British studio was daring to attempt. A truly ugly response to a change to No Man's Sky's release date was one of the first blemishes on the game's otherwise spotless record. And if one were inclined to find a silver lining in that darkest of clouds, it could be argued that the vitriolic disappointment at least spoke of an intense desire for the the wait to finally be over.

As July drew to a close, the team at Hello Games had every reason to feel confident. Then, the leak.

Just over a week ago, with No Man's Sky just ten days away from its official launch, a copy of what seemed to be the full game appeared online. Numerous playthrough videos followed, more copies surfaced, and stories analysing the game's (supposedly too short) length were published. Before long, various outlets in the consumer press had obtained a copy, too, and a game designed to simulate the inscrutable majesty of the universe was having its closely guarded secrets laid bare. For a developer nearing the end of three years of hard work, it is as close to a nightmare scenario as one can imagine.

"When you make a game for console - no matter which one - you have to realise the systems developers and platform holders are dealing with weren't built for 2016"

Following the publication of No Man's Sky's Day 1 patch notes, it seems increasingly clear that "spoil" really is the appropriate term. If Murray's descriptions of the changes are accurate, whatever version of the game leaked will be very different to the one that those patient enough to ignore the many videos, streams and click-hungry articles will experience. There are new paths through the game, entire storylines have been rewritten, key gameplay systems have been given more depth and detail, while seemingly everything that exists in its universe has increased in density and variety by orders of magnitude.

Within those patch notes, under the heading "Exploits," Murray makes a telling remark. "People using these cheats were ruining the game for themselves," he said, "but people are weird and can't stop themselves."

The question, then, is could the industry do more to safeguard players against that tendency? Even if you didn't watch the playthrough videos, and even if you didn't actually click through to the articles criticising No Man's Sky for the speed with which it could be completed, if you're engaged with the discussion around games at all it is near impossible to avoid this material altogether. The ripple effect of this minority of impatient gamers travels so much further than just their own experience. It alters perception and expectations, and mostly in negative ways.

Speaking to Game Informer at QuakeCon this weekend, Bethesda's Pete Hines articulated the frustration of seeing a game leak so close to the point at which people could experience it as intended. "I don't think people realise how upsetting this is. And how much it bothers and hurts the devs, and all of us," he said. "You put years of your life and energy into something and somebody goes and gets it early and, regardless of whether there's a day one patch or not, it sucks.

"As for the No Man's Sky folks, I feel for them, and for any dev that has to go through it," he said. "It really sucks. It's not the fans fault that the store decided to sell it. If I walked into a store and they said, 'Here's Dishonored 2,' yeah, I would want to play that."

This is the bitter contradiction that developers have to reckon with in these moments: understanding what it is to be so enthusiastic for a game, and yet also knowing better than anyone the degree to which the experience through that indulgence. In the case of Hello Games, the degree to which the Day 1 patch will change and improve the game is more pronounced, and so the damage done is also intensified. According to Hines, the industry offered gamers a solution to this issue only a few years ago: the Xbox One's original strategy of being "always online," which was both poorly communicated and roundly and vehemently rejected by early console adopters.

"Remember that conversation a few years ago about always online? Guess what that stops?" Hines said. "It stops people from getting the game early and playing it before they are supposed to. There are plenty of reasons to be unhappy about that, but one of the things that it actually did was prevent people from playing it early."

Hines also praised Blizzard's decision to sell boxed copies of Overwatch early because, as an online multiplayer game, the disc is effectively a paperweight until the servers are turned on. However, "you can't do that with single player games like Dishonored 2. I can't force you to connect to activate the game. That really screws over people without internet connections. That's the rub." And that'sm a rub that Microsoft would have attempted to eradicate with its original vision for the Xbox One.

"Anybody arguing that a game should be done when it goes 'gold' is living in the 90s"

However, Blizzard's strategy does provide some perspective that is useful here, specifically around the way in which both the players and the industry fail to recognise (and often embrace) obstacles to their own progress. After all, Overwatch is far from the first online multiplayer game to be sold in a box, and yet Blizzard ignoring its own midnight launch seemed like a radical idea. As we noted at the time, the midnight launch is a relic from a period when blockbuster games like Overwatch didn't exist; a time that has all but disappeared, and yet companies are still conflicted about abandoning its remnants.

Vlambeer's Rami Ismail made a similar point in relation to No Man's Sky's problems, though specifically aimed at the archaic systems by which games are certified on console. In his article, which is well worth reading in its entirety, Ismail makes it clear that his argument is not about any specific console or any specific product, but rather the entire cert process and how it leaves console developers (even those making digital games) open to the kind of issues that Hello Games has encountered.

"When you make a game for console - no matter which one - you have to realise the systems developers and platform holders are dealing with weren't built for 2016," Ismail said. "These systems are legacy systems, built upon legacy systems, built upon legacy systems. As such, many of these systems are unwieldy, complicated, intricate and really built for teams that can afford to hire more people to read the manual and figure out the systems. These systems come from an age before indie, and some of the manual pages still refer to mailing copies by postal mail. Despite that, the console creators and their teams all work super hard to ensure developers have a smooth process, improving their systems where possible without touching the legacy foundation, and ensuring players get a functional game."

Much of the article will be familiar to readers of a site like GamesIndustry.biz - if not to the average consumer - but Ismail effectively communicates both the virtue of the "Seal of Quality mindset" that gave rise to the complexities of the certification process, and its myriad deficiencies when compared to the freedom and lack of friction offered by digital marketplaces like Steam, Humble and GOG.com. "No matter what developer you ask, you'll find most developers understand why it exists, and we all really appreciate all the people working super hard to ensure our games are working right," he said, "but we tend to all hate 'cert'."

Within the "giant book of checkboxes" that certification entails there are any number of ways a developer can "lose a week" in the process of reaching a satisfactory build, meaning that the process can, in some cases, take several months to complete. However, in an age of Day 1 patches and the diminishing importance of physical sales, the version of a game that passes certification doesn't need to be final - only stable. "Certification is technical," Ismail continued. "It doesn't bother with what the game is, it just concerns itself with whether it works technically." With "one to three months" between passing cert and the launch of the game, there is ample time to add content, refine systems, and things generally of the type that Hello Games intended to add to the non-leaked, launch version of No Man's Sky.

"Remember that conversation a few years ago about always online? Guess what that stops?"

"So in the hypothetical example of No Man's Sky, when No Man's Sky launches, for most people, it'll launch into the intended experience thanks to the Day 1 Patch. That build is as close to what the developers envisioned as they worked, learned and improved upon that vision. That's No Man's Sky. The version that is on the disc, however, is months old. The only way to avoid that kind of thing is to not launch on disc.

"One could argue that developers then, should make certain that a game is perfect when they submit it to disc, which is not an invalid stance. It's just an impractical stance... Anybody arguing that a game should be done when it goes 'gold' is living in the 90s."

"Developers care about the games they make, and we're trying to make the best game we can for our players. We'll take every opportunity we can get for that. If consoles operated like Steam did, No Man's Sky wouldn't have a Day 1 Patch, because the build you'd download and play when it comes out would've been submitted comfortably a few days before launch. Day 1 Patches aren't necessarily a failure on the developers or the platforms side, they are the result of people that care about what they make, trying to deliver the game the audience expects by the date they expect it, while everybody involved is struggling with outdated systems on cutting-edge technology."