Brenda Romero's guide to becoming a game designer

The Wizardry developer shared insight into this crucial role during last week's GamesIndustry.biz Career Fair

Veteran designer Brenda Romero urged aspiring game makers to build a portfolio with small projects -- and, more importantly, finish them -- if they hope to establish a career similar to hers.

Romero kicked off the second day of the GamesIndustry.biz Career Fair during EGX Rezzed in London last week with a talk entitled 'So you want to be a game designer?'. Before exploring what defines this coveted role, she launched into the session with vital survival advice.

"Be nice to programmers," she laughed. "Be very, very nice. Because at the end of the day, the programmer is going to be the one getting your feature in that you're really, really hoping will stay in. And they will remember all that currency you built up when you were irritated with them or anything else, so always treat programmers with the utmost respect.

"Game designers are ultimately experience planners. We're trying to figure out how to make your time in this world challenging, interesting and cool"

"That's not to say you should be mean to artists, fellow designers or your producer, but programmers... at the end of the day, a game lives or dies on its programmers."

Romero then revealed the three most common questions she's asked when revealing she's a game designer. The first is, 'Did you make Fortnite?' -- "No, I'd have a fleet of Lamborghinis parked outside if that were the case" -- and the second is, 'Do you spend all day playing games?', to which she answers, " Kinda, yes."

She said her is constantly coming up with new game or feature ideas at the most inopportune times, but that the way to explore these ideas is through play.

As an example, she called on members of the audience to come up with a year (1987), a setting (California), and a job (con artist), and began coming up with a game design around those ideas. Romero stressed that it's important to "think about the verbs", or what players will be doing. If you're a con artist, the goal will be to make money, which opens up the idea of robbing banks and so on.

The idea is that by combining different concepts and settings, game designers "create the virtual worlds in which you play."

With the 1987 con artist example, Romero was brainstorming alone but she said she'll often sit with her team and ask what actions they would expect to have in any given setting.

"It's free. Well, it's not free because you're paying people to be there, but it's a cheap way to figure out how people will want to interact with a space before the space even exists," she said.

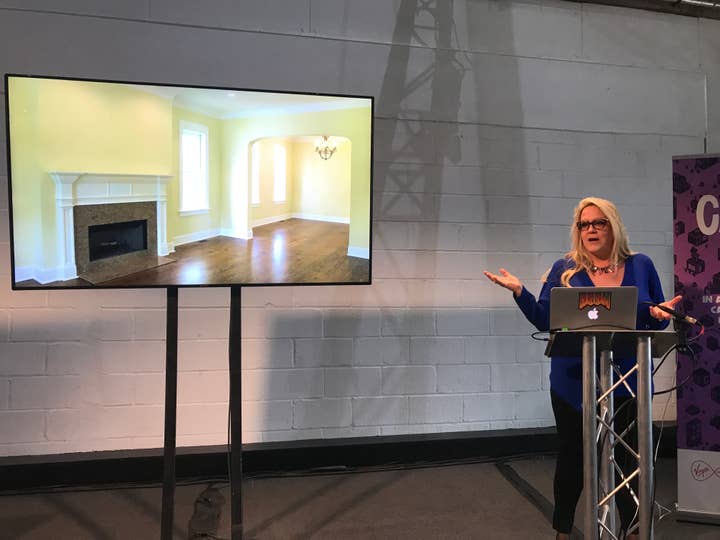

The final question she is often asked is: 'What does a game designer do?'. When asked by her family, Romero tends to refer to herself as an architect -- laying out plans for coders to build the world, and the artists to serve as interior decorators.

But even this doesn't quite convey what a game designer does, she admitted. On the screen, she brought up a picture of a beige, unspectacular lounge, and pointed out that an architect has designed it, a builder has built it and an interior designer has decorated it, but, "There's nothing interesting about it."

"This is an incredibly boring place," she continued. "Imagine if in the next room there's a million pounds on the floor and you just have to go in and get it, but there's also someone guarding it so you know it's not going to be as easy as, 'Oh, are you here for the money? Here you go.'

"It's important to recognise as a game designer that nobody wants to read your design document. Nobody. Especially if we can just play a game"

"Game designers are ultimately experience planners. We're trying to figure out how to make your time in this world challenging, interesting and cool. Consider Minecraft for a second -- someone had to think about these questions: What happens when you walk? What happens when you hit a tree? What happens at night? Basically, in a nutshell, game designers write the rules of play. You pass go, you collect $200."

Having said that, Romero stressed that game design is not about simply writing a rulebook about how to jump or carry out other actions. Instead, designers have to "teach people how to play through the process of play".

Romero moved on to give examples of design documents and noted she is often asked how important these can be when applying for a game designer role. Can you get a job simply with a good design doc?

"Yes, I'd say you can," she said. "I'd certainly hire someone who worked on D&D, and D&D is sort of a giant design document for a game that you can play at a tabletop. But the flip side is if one person has a game and another has a design document. If I can play a good game, I'm going to hire that person over the one with a 180-page design document any day.

"Ultimately, it's important to recognise as a game designer that nobody wants to read your design document. Nobody. Especially if we can just play a game. And if your design document starts with a whole load of story, I don't care. Wrong profession. If you want to be a narrative designer, absolutely, I care about your story. But otherwise, I need to know what the mechanics of the world are. The second-to-second play is the most important thing. If you can't hold me second to second, I don't care about your minute to minute, and I won't care about your grand cutscene in Act Five."

She summarised the role of a game designer as a job in which you, "create worlds, goals, challenges for the player, and an experience."

"We create and play games because we want to convey a particular experience, whether it's to survive a zombie apocalypse or rescue the prince from the castle," she said, adding, "I'm done rescuing princesses at this point, I'm only rescuing princes."

Romero detailed how designers can be both generalists and specialists, breaking down the differences between different disciplines. Among those she discussed were lead game designer, level designer, content designer, economic game designer, creative director and the deceptively generic position of game designer.

But looking at entry level priorities and talking to the many students and aspiring designers attending the career fair, she addressed how they can start improving their chances of securing such a position immediately.

"Don't wait to get to college, just start making games. It doesn't have to be a good game. In fact, it can be an abysmal failure"

"Start making games," she said. "Don't wait to get to college, just start making games. Now, notice there's no adjective there -- it doesn't have to be a good game. It could be a terrible game, in fact it can be an abysmal failure."

Romero pointed out that Doom, the iconic shooter by her husband John, was actually the 80th game he had developed, and that he has previously said his early, unreleased games are among the worst he's ever played.

"But you've got to start now, and start small," Romero continued. "Recreate a classic arcade game. The amount of students who get to their first year of college and go, 'Finally, I get to make my version of World of Warcraft'. Well, good luck. You're going to do that by yourself in four years?

"Start with something small. And ultimately these small games will give you a portfolio. If you have to learn something, if someone gives you an assignment to figure something specific out, do that in the context of a game so that you are building your portfolio as you go."

She said that when she's reviewing job applications, it always comes down to portfolio versus resumés for her. The best candidates are the ones that can demonstrate the most things they have actually worked on.

"There are graveyards full of dead game ideas, things that never got finished," she concluded. "If I can see an actual portfolio full of finished games, or even just prototypes, that puts you well ahead of any resumé. Make games on the weekend. They can be analogue games, or you can go to game jams.

"The most important thing is to finish your games, finish what you start, even if it's just closing up early and saying, 'This is a prototype but I decided not to go any further, it's only one level'. Finish it and have stuff to show because that's what employers are going to want to see."