Why culturalisation matters as much as localisation

Kate Edwards discusses how to approach culturalisation, and how to navigate sensitive themes so your game can reach wider markets

From Skyrim to Super Smash Bros, culturalisation is an integral part of every single game we play, whether you realise it or not. That's been Kate Edwards' specialty ever since she created geocultural and geopolitical content strategy agency Geogriphy 15 years ago. During her Plan B Project talk earlier this week, Edwards addressed the key reasons why culturalisation matters and how it can help developers improve their world building.

"A lot of times when we think about world building, we go to massive RPGs like Skyrim and GTA, but we can't forget that even mobile games have very fully realised worlds," Edwards said. "Even things like Angry Birds -- [its world setting] might be simple by some people's standards and yet it is still very valid.

"There are things that may or may not be compatible with cultures around the world"

"Any kind of game has a certain narrative structure, it has a world, an environment that has to be built, and there are certain things within those environments that may or may not be compatible with cultures around the world."

This is increasingly important as the games industry grows beyond its historical markets, with China surpassing the US as the largest gaming market in the word in 2019.

"The global game industry is massive, and we're still seeing tremendous growth across all the regions of the world, but the interesting thing is a lot of that growth is not happening where game developers typically think it's happening. Game creators will make their game with the intention of selling in North America and Western Europe, but the reality is that that's not where it stops. China has become this massive consumer powerhouse for entertainment media and a lot of game developers are trying to expand their scope."

But it's not only about China -- growth is happening in a lot of emerging markets too, especially in mobile. Edwards quoted a report from PricewaterhouseCoopers, pointing at 22% year-on-year growth for games in Nigeria for instance. Vietnam and India are also booming markets.

Reaching these markets requires developers not only to invest in localisation, but most importantly in culturalisation.

What's the difference between localisation and culturalisation?

While localisation will remain an essential aspect of making a game, culturalisation is the next step as game developers start to realise there's more to other cultures than language.

"Localisation primarily is focused on language translation," Edwards said. "It's language adaptability, it's linguistic translation to make the game content linguistically compatible to the local market. [But game developers] also have to understand: will this game content be compatible with that local market? The theme of the game, the gaming experience, all that kind of stuff, is this the kind of game that people in that market want to consume?

"We're not just talking about language -- we're talking about a much broader level of adaptability"

"That gets to a deeper cultural level, and that's where culturalisation comes in, because we're not just talking about language -- we're talking about a much broader level of adaptability."

The two types of culturalisation

- Reactive culturalisation

When Edwards works on a project, the type of culturalisation she's asked to do can take two forms. The first is called "reactive culturalisation".

"Typically this is where I am asked to look for things that are going to be a problem," she said. "[The developer] wants to make sure there's nothing in there that's going to cause a negative reaction from the audience playing this game."

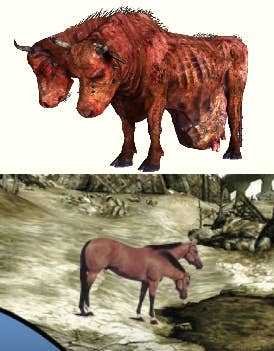

Edwards took the example of the two-headed Brahman bull in Fallout 3 to illustrate what reactive culturalisation can look like.

"So in the original game, the Brahman bull has mutated and has two heads, and that was not going to work in India, because Brahman bulls are sacred to the Hindu faith. And so we went back to the developer and showed them my poorly photoshop two-headed horse (see right) and said: let's use this instead because that would have been fine.

"But unfortunately, because of the schedule and because they felt that frankly the Indian market was not important enough to make this change, they didn't make the change. And so because of that one object in the game, Fallout 3 did not sell in India."

- Proactive culturalisation

The second type of is proactive culturalisation, which is enhancing a product specifically for a market.

"We actually look for ways to make [a product] more appealing to a specific country, culture, or region," Edwards said. "An example of proactive culturalisation is when Marvel partnered with a studio in India to create an Indian version of Spider-Man. The initial reaction was very positive, but unfortunately this is an example where what people really wanted was Peter Parker from New York City.

"When you're dealing with a popular IP like Spider-Man, people don't necessarily want you to culturalise it, to make it adaptable for them. Because they're already familiar with who the original Spider-Man is.

"So this is an example where it was really good intentions, but ultimately that's not what people wanted in this particular market. Proactive culturalisation doesn't always work the way you want it to, you have to really do your research and understand exactly what you're doing."

When to start culturalisation in the development cycle

Making sure your game is going to be compatible with local worldviews needs to be done sooner rather than later.

"Typically, most culturalisation occurs early on, it does not occur later like localisation," Edwards said. "Localisation has to wait for the text to be done in order to start the translation, whereas with culturalisation my work often begins on a project very early.

"For example, I've worked on all the Bioware projects from the last 18 years and for every one of those projects we were looking at things right from the start, reading the draft script, looking at the concept and trying to understand: What is this world? Who is in it? What do they do? Are there politics? Are there religions? Because if I can see early on what they're trying to create, I can understand and course-correct right from the start, [see] whether or not things are going to be compatible with different cultures around the world.

"That's really the key. Course corrections early on [are] really cheap and easy to do compared to finding that later in the product cycle [when] it's going to be very expensive to fix."

What to consider as you step into culturalisation

- Think about your values and goals

There are multiple aspects to consider when thinking about culturalisation of a game, and one is to choose what you deem acceptable or not.

"The point here is that you have to decide, when it comes to culturalisation issues, where you draw the line on what you will or will not change," Edwards said. "So for example, if you're releasing a game in China that uses a real map, if that map does not show Taiwan as part of China, your game will not be sold in China."

"You have to decide where you draw the line on what you will or will not change"

- Keep informed about geopolitical changes

The world around us is constantly evolving culturally, ethically and geopolitically. Make sure you stay informed about those changes.

"All it takes is one regime change in a certain market and the rules for content might change, and so you have to be aware of that," Edwards said.

She took the example of Germany changing its rules on Nazi symbology, and the impact it had on Wolfenstein. Another example she took was the Blitzchung controversy, where Blizzard removed professional player Chung 'blitzchung' Ng Wai from a Hearthstone competition after he showed support for anti-government protests in Hong Kong during an interview.

"To me this was an example of a company that had no clue what it was stepping into," she said. "I think Blizzard failed miserably in this example, and their explanations for what happened were really tepid and weak. This is just an example where things went awry for the company and the politics that were happening on the ground in the moment caught them off guard to a certain degree.

"And of course Blizzard's not alone -- they're just a more recent example. I'm just using them as an example because it does happen a lot to different companies"

What are the most sensitive themes to keep in mind?

Edwards identified five particularly sensitive themes for developers to keep in mind when it comes to culturalisation.

- History

Always remember that history is a matter of perspective. Edwards gave an example dating back to the original Age of Empires, which she worked on before its release in 1997.

"The original scenario that was in the game is [when] Japanese invaded the Korean peninsula [then known as the Joseon Empire]. Now, that's what history tells us happened, but then we released the game in Korea and the Korean Ministry of Information said that never happened."

Real-time strategy games were very popular then and Microsoft was trying to expand its games around the world, so Ensemble Studios didn't want Age of Empires to be banned in Korea.

"In order to do that we [had] to make some decisions," Edwards continued. "The decision was ultimately made to make a patch for Korean players, in which the Joseon Empire invades Japan instead of the opposite. Now, as you might imagine at the time it created a lot of debate on the development team, about the nature of ethics and the nature of truth. And I think it was a very healthy debate to have because a lot of people were saying: this is wrong, we're changing history for a specific government."

She then reminded the team that when she was working on the Encarta Encyclopedia with Microsoft, the French and Italian versions of the Encyclopedia had different heights for Mont Blanc, because at the time the governments did not agree on the exact height of the mountain.

"A lot of cultures maintain their local expectations based on religious belief and we have to be very sensitive to that"

"So that was a physical fact that was actually different, because in the local markets an encyclopedia has to conform to educational standards," Edwards pointed out. "So if this market says this person is the inventor of the radio and this market says: no, this person is the inventor of the radio, we have to change that fact according to those different markets or else it's not going to conform to educational standards -- and, therefore, it will not get released in that market."

- Faith

Faith and religion are obviously sensitive topics and game developers need to respect local beliefs.

"A lot of the cultures that we send our games into maintain their local expectations based on religious belief, and we have to be very sensitive to that as game creators if we want our games to be viable in those markets," Edwards said. "In Hitman 2, they [recreated] a sacred place, the Golden Temple, which is the center of the Sikh faith in India. They made the main character go into the Golden Temple and actually start killing Sikhs at their most sacred place in the world. That's highly inappropriate."

- Inclusion vs exclusion

The inclusion versus exclusion theme refers to people who might perceive an inequitable treatment in your game, because of their gender, nationality, or ethnicity. To explain this, Edwards took an example from Resident Evil 5.

"They showed these pictures of this Caucasian male shooting sub-Saharan African villagers," she said. "The excuse from the company was: what's the big deal, they're zombies. It is a big deal because what the developers do not understand is that showing that kind of imagery, is really politically and ethnically charged."

- Intercultural dissonance

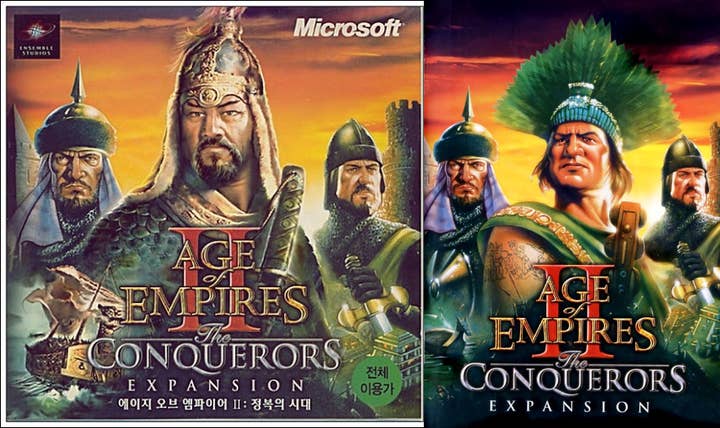

Intercultural dissonance is a larger issue that can relate to any kind of tension over a historic or political issue -- it can be a tension between two cultures. For example, when Age of Empires 2 came out in 1999, the box art had a Japanese samurai on it, which Korean retailers did not approve of.

"The reason had nothing to do with the game itself," Edwards said. "It has everything to do with a geopolitical dispute between Japan and South Korea. So a lot of retailers said: I don't want anything Japanese-related on my shelf."

Microsoft ended up making cover art specifically for Korea when an expansion was released.

"But the whole point about this example is that a lot of times it's not about the games we created," Edwards said. "It's about the political, social, cultural context into which the game is being released at that moment. It's also about looking forward: when is this game releasing and what is actually happening in certain markets while this game is releasing?"

She also touched upon gestures, which can mean wildly different things depending on the culture. She took the example of the sign of the horns, but this applies to more gestures that you may think.

"If you're going to have gestures, you have to be very careful about how they're portrayed and think through the context"

"I gave a lecture at Facebook headquarters a few years ago and I pointed out to them that the thumbs up gesture is actually the same as [giving the middle finger] in some countries. But yet that's the corporate symbol of Facebook. We have to be very mindful. If you're going to have gestures in a game you have to be very careful about how they're portrayed and think through the context."

- Geopolitical imaginations

The last layer that could be sensitive is what Edwards calls geopolitical imaginations.

"Now this is where governments use cartography and maps to reinforce what they believe they own, the territories they own out here in the real world," she said. "They use maps as a form of propaganda, as a form of enforcing their political will on the content creator. So for example, Hearts of Iron games were banned in China because Taiwan and Tibet were not being shown as part of China."

These examples do raise ethical questions, and that's why freedom of creativity is something Edwards likes to touch upon in her talks as well.

"It almost always comes up when I give a lecture on culturalisation," she said. "I think a lot of people when they hear a talk like this are like: 'wow, this sounds like I need to change everything because I'm supposed to make everybody happy'. No, that's not my point.

"My point is that you need to exercise your creative vision the way you want to exercise it, but you can't expect that creative vision to translate in a line with expectations and cultures all around the world. And so you have to be extremely conscious of the fact that all of the creative decisions you're making during the world building process will have some dimension that either will be compatible or incompatible with those markets.

"And it's up to you, and you alone as the game creator, to decide what is ultimately more important to you."