We’re in the Wild West of generative AI: Beware the outlaws | Opinion

Technology is again out in front of legal and commercial frameworks – but those being taken in by the "this changes everything" hype could learn some lessons from the past

Sign up for the GI Daily here to get the biggest news straight to your inbox

Nearly a quarter of a century ago, in the summer of 1999, a start-up company launched an application which instantly became a global phenomenon. We were in the heady days of the Internet bubble, with the dot-com crash still a year away, and the founders of this new company had identified an inflection point in the development of technology.

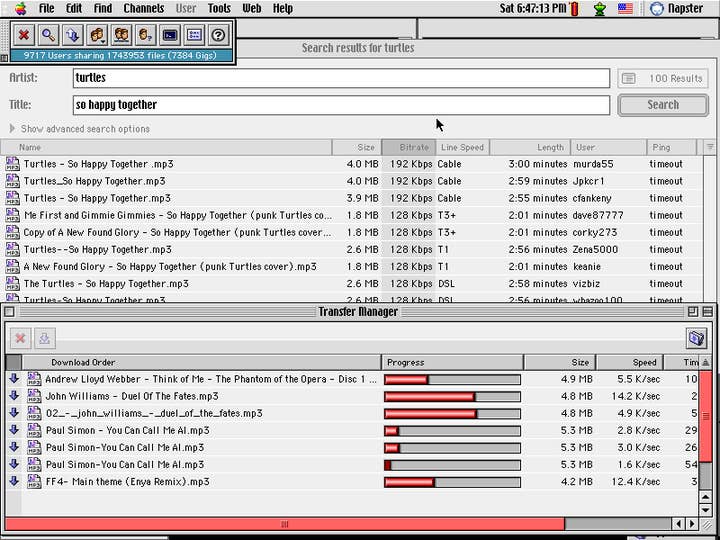

Sean Parker and Shawn Fanning hit upon the moment where network speeds and costs dropped so low that high-quality music files could easily be shared between ordinary users, effectively lowering the cost of distribution for this medium to zero. Their application, Napster, provided an easy way for users to take advantage of this, and the response was instant – within months it had tens of millions of users, an immense number in an era when Internet access was still far from universal.

Enormous amounts of music were transferred over the service, and as well as providing a full catalogue of contemporary popular music, the application became beloved of enthusiasts because it opened up access to music by niche artists, difficult to find albums, and even bootlegs and unreleased tracks.

Napster changed the world of music distribution forever. It pointed a flashing neon finger at a technical reality that many executives in that business would have preferred to ignore – that digital distribution had become entirely inevitable – and paved the way first to digital storefronts and ultimately to the streaming services that now dominate that sector. There was just one problem; Napster didn’t have permission from musicians or publishers to distribute their work.

A new technological frontier and the Wild West atmosphere that springs up around it is exciting and innovative, sure – but it’s also dangerous

The whole enterprise was built on stolen content. The company itself didn’t send or receive any of that content, but the software it had created was explicitly designed to allow users to do so. When the US courts ordered Napster to start restricting access to infringing material upon being notified of its location, the gig was up; the service was shut down by summer of 2001.

In retrospect, it feels absolutely wild that Napster was an actual start-up company – a legal entity, with its creators publicly listed as founders and officers of the company. This was a company with commercial ambitions, whose sole product was a piece of software explicitly designed to be the most efficient way possible to pirate music. It wasn’t even the only one!

From AudioGalazy to LimeWire via the likes of Kazaa, there were a bunch of companies built around applications, networks, and protocols that were explicitly designed for music piracy. Networks had reached a point where music distribution was possible, even easy. This technological advancement opened up a whole new landscape, and for a few years in the late 1990s and early 2000s, that landscape was the Wild West.

Some people believed that it would stay that way – that the advent of zero-cost distribution changed things so fundamentally that old business models would collapse, and music recordings would effectively be forced to become public domain, validating the whole approach taken by companies like Napster.

I’ve been thinking and reading a lot about that era lately, because while history may not repeat itself, it does certainly rhyme – and we’re living through a very similar moment right now. Just as network speeds and capacities inched their way towards the tipping point where they were capable of collapsing the distribution cost of music, so too has progress with generative and predictive machine learning models inched its way painstakingly over the past decade or two until the point where the models’ capabilities hit an inflection point, enabling technical marvels like MidJourney and ChatGPT to exist.

Just as network capacities created some cultural and commercial inevitabilities that are only really apparent with hindsight, it is probable that generative AI will change a number of industries in very fundamental ways – which will seem to have been entirely inevitable all along when we look back upon this era in ten years' time.

The most striking similarity, however, is that we are absolutely in the Wild West era of generative AI. Consequently, we are surrounded by a mix of chancers, outlaws, fast-and-loose entrepreneurs, and wild-eyed philosophising about how This Changes Everything so none of the old rules ought to apply any more.

It’s a mix that anyone from the Napster era would find very familiar – and one of the most familiar aspects is that these people aren’t anarchistic characters releasing software and posting screeds from behind a screen of anonymity, hidden from legal consequence. They’re wearing suits and sitting in boardrooms. They’re being interviewed in newspapers and on TV. They’re giving TED talks.

Generative AI is a major business push, with billions of dollars behind it and names like Microsoft and Adobe fully committed – none of which changes for a single second the fact that almost all of these models, and certainly all of the major, popular ones, are built on a mountain of stolen content, all supported by the most flimsy of legal justifications.

A new technological frontier and the Wild West atmosphere that springs up around it is exciting and innovative, sure – but it’s also dangerous. Most of the companies that sprang up to take advantage of the new frontier in media distribution around the turn of the millennium were bankrupt or sold for a pittance within a couple of years, after the legal system caught up and confirmed that yes, new technological frontier or not, you’re still not allowed to run a business whose objective is to make it easier to steal stuff.

I’m not saying that’s the fate that awaits OpenAI or MidJourney (although, to be clear, I’m not not saying that either), but some people in this space are going to get burned.

That includes companies in the games industry, where getting out in front of their skates on the topic of generative AI is becoming quite a hobby for some people.

Generative AI is a major business push, with names like Microsoft and Adobe fully committed – none of which changes the fact that almost all of these models are built on a mountain of stolen content

Valve is determined not to be one of those who get burned. The company has hardened up the line it’s taking on AI-generated content in games on Steam – it won’t approve games which include it. The company says this isn’t an opinionated stance, merely a reflection of legal realities – and it’s entirely correct in saying so.

There are many jurisdictions in which the legal status of AI models and of the content they create remains unclear; and there are quite a few in which the status is pretty clear, merely obfuscated by a cloud of wishful thinking from AI enthusiasts. Large AI models are trained on huge amounts of copyrighted data, usually without permission of the copyright holder, and sometimes despite the explicit denial of that permission.

Proponents claim that this is no different to an artist walking around a museum and looking at paintings before going home to paint his own work. In reality, it’s been repeatedly demonstrated that most if not all AI models can be persuaded through careful prompting to yield almost exact copies of parts of their training data.

Even if you’ve obfuscated content by storing it as interconnected weights across layers of digital neurons, you’ve still stored it, not merely learned from it as a human would – and in most cases, the operators of these models don’t have the right either to do that, or to use it as a basis for digital remixing, which is essentially what AI models do.

New technological frontier or not, you’re still not allowed to run a business whose objective is to make it easier to steal stuff

Depending how courts and legislatures in various places choose to interpret that (and I do not for a single second envy the task of the lawyers and experts who are going to have to try to explain these systems to bemused judges and lawmakers), this will mean that either the models themselves are judged to breach copyright, or that works created with those models are judged to breach copyright, or both.

Making bets on how rulings and ultimately legislation in major jurisdictions will go on this topic is a fraught business. I’d argue that it’s more likely that the models get in trouble than the works created by them, except where a specifically identifiable breach is shown in the case of a piece of text, image, or audio content – but a kind of "guilt by association" assumption where every product of a copyright-breaching model is considered to also be in breach is certainly not impossible.

For Valve, and any other distributor, that creates an intolerable risk. They could be found to have sold and distributed copyright-infringing materials, and given the widespread public debates about this aspect of AI, claiming to have been unaware of this possibility may not serve as a defence.

Without very clear guidelines and case law on this matter in most jurisdictions, distributors have little choice but to reject games with AI-generated content. The moral questions around AI are incredibly important, but irrelevant to this specific issue; the question that’s relevant is the extent to which the distributors have to cover their asses.

That Valve won’t touch these games should be a wake-up call for everyone in the industry who’s been starry-eyed about the potential for AI to reduce their costs and speed up their development processes – going too far down that path without absolute legal clarity risks disaster.

Look, I’m far from an AI refusenik or luddite! I’ve written here in the past about how exciting the potential of technologies like LLMs is for games, and I use systems like ChatGPT and GitHub CoPilot every day. Wearing my other hat as a university professor, I’m even in the minority of people in my field who encourage students to use ChatGPT as a tool to assist their work. However, the idea that it’s going to be possible to build whole swathes of game content through simple text prompting, rather than needing humans to draw, write, compose, and perform that content, is naive at best and incredibly dangerous at worst.

That Valve won’t touch these games should be a wake-up call for everyone in the industry who’s been starry-eyed about the potential for AI to reduce their costs and speed up their development processes

Creating content from scratch with a generalised AI – whether it’s images, text, voiceover audio, or anything else – is something that no game company should ever be doing. The resulting content is a copyright minefield, with the worst case scenarios involving a developer being found to have illegally included copyrighted material in their game, or to have developed the game using copyrighted material illegally built into a key tool.

It’s worth asking whether any of the vendors such as Unity which are currently enthusiastically adding generative AI features to their tools are willing to indemnify developers against any legal liability arising from the use of those tools. Perhaps some are – I’m not sure if that’s brave or foolhardy – but for the most part, it’s caveat emptor, and there are some insanely big caveats here.

Honestly, even if it’s decided that this content isn’t infringing other people’s copyright, the best case scenario may well be that nobody gets to own the copyright over the resulting content, because it's not deemed to have had sufficient human involvement in its creation. This would result in game assets ending up in the public domain, with the developer losing control over how they are used by others.

Generative AI is going to revolutionise many fields, and game development is probably going to be one of them – but not like this. It’s going to be hell of a lot harder than opening a window to a fantastical piece of software that can replace artists, writers, voice actors and musicians and just telling the magic mirror on the wall what you want it to make for you.

Generative AI is going to revolutionise many fields, and game development is probably going to be one of them – but not like this

AI systems can be trained on your own content, allowing the streamlining of pipelines for these processes – letting your artists remix their own artwork, or allowing your writers to use their scripts to train LLM-driven characters that react dynamically to players. These things are harder, requiring you to have a lot of your own content to start with, and to have the expertise to train and operate an AI system on that content, but this seems like a much more likely model for how development pipelines will ultimately integrate these tools.

Yet even this isn’t really possible right now – it’s technically possible, sure, but such systems still rely on a large-scale AI model as their foundation, and the legal status of those underlying models remains incredibly uncertain.

Until such time as there are models out there which are fully in the clear legally – either trained entirely on authorised material with a full paper trail, or covered by a new legal framework which permits and controls their use of a wider range of copyrighted material – companies should be treating AI as a "look, but don’t touch" technology.

Progress often puts technological reality out in front of legal and commercial frameworks, and the Wild West that results is exciting and innovative, but also controversial and dangerous – and like the Wild West we see in games and movies, very much full of outlaws, snake oil salesmen, and a million ways for the unwary and incautious to meet a sticky end. Ultimately, no market of this size and scale will remain the Wild West for long.

Courts and legislatures will drive their railroads through and tame the lands – and some of the outlaws will get rounded up along the way. In the anarchy of these moments, you should always be asking whether something is too good to be true. A business built on letting people freely share other people’s intellectual property was always too good to be true. Is the magic mirror that 'knows' every style of art and will create anything you ask for on command any better?