Reinventing God of War was a battle against doubt

At Devcom 2018, creative director Cory Barlog detailed the troubled evolution of a modern masterpiece

On April 18, two days before the launch of God of War, Cory Barlog hit record on a camera and looked for its review scores. As he grappled with the cascade of nines and tens, he started to weep.

To most people they would appear to be tears of happiness, and joy will certainly have played its part. After hearing Sony Santa Monica's creative director speak at Devcom 2018, however, it's reasonable to suggest that the predominant emotion was relief - sheer, blessed relief.

When Barlog introduced his talk, he said it would detail, "the very doubt-ridden process of making this game." Doubt, he explained, "is a big part of any creative endeavour," and the creation of God of War was evidently drenched with uncertainty for almost all of its five-year development.

"For me, it was about giving Kratos a reason to be better... He wasn't going to be such a dick this time"

This was inherent to what Barlog and his team were trying to accomplish; not a conventional sequel, but a fundamental rethink of what a God of War game could be. Around the time of Ascension - the fourth console game and a series low in terms of review scores - Sony conducted a "brand health study" that indicated waning consumer interest in the franchise. Barlog admitted that there was one quote he will never forget.

"It said, 'God of War is like my dad's muscle car. Uncharted is like a sexy McLaren sports car, and I want to drive that'," he told the Devcom audience. "We had not grown up at all, apparently, so we needed to change."

The biggest single change was in the mythology. SIE Santa Monica considered several options, including Hindu and Egyptian, but ultimately decided to use Norse myth on the basis that it was "more sparse" in terms of landscape and characters. This suited the kind of story Barlog wanted the game to tell, which was different enough to previous games that, at one point, Sony suggested that Kratos himself no longer seemed to belong.

"Keeping Kratos was a big part of [God of War]," Barlog said of his refusal of that request. "For me, it was about giving him a reason to be better... Not a paladin, riding horses and saving the world. It's just that he wasn't going to be such a dick this time."

The team started pitching ideas for a more intimate and immediate God of War game, and there was one concept that Barlog had wanted to use since his time at Crystal Dynamics: a tight camera that never cut away from the player's control. Certain films, most famously Alfred Hitchcock's Rope, appeared as if they had been shot in a single take (albeit with disguised edits), but the central role of action sequences in games was a challenge that film directors didn't have to consider. After a number of what Barlog described as "'Yeah, but...' conversations", he found a model for what he wanted to achieve in the classic John Woo thriller Hard Boiled.

"It wasn't analogous one to one," Barlog admitted, after showing the audience a hospital gunfight that moved from action to character to drama and back to action seamlessly. "But it allowed people to say, 'Okay, I think I get it, I think I understand why we're doing it.'"

Barlog added: "Throughout the development, both fans and the team kept saying, 'I don't know why we're getting rid of the camera. It's so good.' It wasn't until the very end of the game that people would come to me in my office and say, 'I get it. I get why we did that'. I was like, 'Really? Five years and now you get it? You couldn't get it at four years?'"

Doubt is inevitable when doing anything new, and God of War was attempting new ideas in its setting, its story, its characters, its camera, its structure, and more besides. The real challenge of God of War, Barlog said, was "figuring out how to get people onboard with so many things." It was difficult with the small team he started with in 2013, but that was magnified by a massive influx of new staff well before the studio was ready to start full production - before it even had an engine with which to build the game.

"When we started early production, I got 100 people way earlier than I expected; we're talking about a year to a year-and-a-half"

"We had inherited a bunch of people," he said. "When we started early production, I got 100 people way earlier than I expected; we're talking about a year to a year-and-a-half. That's 100 people saying, 'feed me, give me something to do, and also, what is this new game?'

"Getting 11 people on the same page? Very easy. Getting 100 people on the same page? Way harder, and clearly I was not prepared for that."

One of the most useful tools Sony Santa Monica had in familiarising staff with the project was a lavishly produced art book, presented in a rune-laden box, which was created as a pitching tool for Sony Interactive Entertainment's top executives. In the end, Barlog had 150 copies of it made, and distributed to new team members.

"It allowed for team buy-in," he said. "That book saved my bacon."

Barlog wanted God of War to be more open than previous games in the series from the very beginning, but the ambition kept growing based on what he admitted was, "a refusal to cut things." The team was working from a map that Barlog had drawn by hand - "my crappy map" - and prototyping discrete gameplay mechanics that would feature in the game's open landscape. Barlog showed the audience a hunting prototype, brought to life using Maya in glorious low-poly graphics. The game's "first playable" - which is used to "convince the money people that there's actually a game here" - was a clutch of these prototypes, created using a modified version of the engine for God of War: Ascension.

"A very, very modified version of the Ascension engine, which had been getting modified for something else," Barlog said. "A lot of it was broken, nothing really worked right, and then we were repurposing it in ways that it was never really supposed to be used.

"It really made us realise that our process was just convoluted. Part of it was that we were building the engine and tools as we were building the mechanics, as we were designing the mechanics, as we were then designing the levels. All of those groups had to build everything at the same time.

"And that, unfortunately, continued throughout the entire project, because I inherited people a year-and-a-half early, so that meant we were behind a year-and-a-half the whole time. We were never able to catch up, which made it very difficult. Everybody was always waiting for somebody else to finish something to get their thing done. Again, it fuels this concept of doubt for people."

"There was a point where the director of production came to me and said I was going to have to start designing a game without Atreus"

The single biggest source of doubt, though, was Atreus, who was at once vital to the vision for the game and a daunting technical challenge. Not only did Atreus not appear in that first playable, Barlog said that it took another three years afterwards to get the code for Kratos' son to work properly. "The concept of Atreus scared a lot of people," Barlog continued. "It scared everyone on the team, it scared the executives, because I didn't want to do just an additional character delivering narrative... They definitely thought it was too ambitious. I was like, 'no, no, no, it's going to be fine, don't worry about it.'"

Barlog and his lead programmer paid a visit to Naughty Dog, which had attempted a similar feat in the Uncharted games. The idea was to get a "reality check" on the task that lay ahead with Atreus, which Naughty Dog's AI team delivered over the course of several hours.

"Outwardly, I was saying, 'yeah, this is fine'. But inwardly it was gloom and doom. Naughty Dog worked years on trying to get this thing and ended up having to throw a bunch of stuff out and start over. Then we finished, we went outside, and my lead programmer was expecting me to say, 'you're right, this is crazy, we can't do this.' But I'm like, 'this is easy, man. This won't be so bad.' Even though, inside, I'm feeling a tremendous amount of doubt.

"[Atreus] was on the chopping block many times throughout the duration of this project. There was a point where Yumi Yang, the director of production, came to me and said I was going to have to start designing a game without Atreus... We couldn't afford it, it was too big, too unknown, too many things we were trying to change.

"I was very childish, and designed the most expensive arthouse game you've ever seen, which had Kratos saying three words throughout all of it. She realised what I was doing and said, 'fine, fine, keep him."

God of War made its full public debut at E3 2016, in an ambitious live gameplay demo backed by a full orchestra. The capacity for that idea to blow up in Sony Santa Monica's face was obvious, and Barlog admitted that he was "pretty insane" for pitching the concept at all.

"Literally two days before the demo, one person blew up at me on the floor and said, 'You are ruining this franchise, you are absolutely going to destroy the brand we built, and you're doing it live. You're such an idiot!' I was like, '...uh, thank you?'

"I don't think I'll ever do that again. I don't think people should be under that kind of pressure. But it went well. It went better than any of us could have expected. Even the guy that freaked out at me and told me I was going to ruin the franchise apologised, and said, 'okay, yeah, maybe you won't totally ruin it'.

"It was great, man. For about ten minutes, it was great."

"I wanted to give up many times throughout this game... At the end of the game there were some dark, dark points"

Barlog's satisfaction lasted exactly one minute longer than the E3 demo, and that took four months of work to create. Sony Santa Monica now had to create at least 30 hours of content, which Barlog described as, "three years of work, but we only had two years to make it." Indeed, the first internal launch target Barlog was given afforded even less time.

"That was really rough. We had an original release date in October of 2017, and it wasn't one we chose. It was one that was delivered to us, like a present... I was like, 'What are you talking about? We're not going to release in Call of Duty times. That's nuts.'

"But we were always in constant talks. Literally every single day: 'Hey, this thing that you said was going to be small? It's twice the size now. What's that all about?' I got really good at acting surprised: 'Huh? Wha? Really? Let me go check that out.'"

Throughout his talk, Barlog talked about the skill of his team in the most glowing of terms, but he credited his "amazing producers" with the fact that God of War was completed less than two years on from E3. As we reported in an article earlier this week, even six months before release the game's all-important combat was in a state to leave Worldwide Studios president Shuhei Yoshida "horrified" by what he played.

And it wasn't just combat. Barlog admitted that he "underestimated" the difficulty of designing a logical, user-friendly UI for the game's intricate upgrade system. "The initial menus were tragically dense and confusing and un-fun," he said, until he brought in a dedicated UI designer to make sense of it all. Even the map, such a vital component in a game that encourages exploration, wasn't added until the final two playtests.

"It's really scary to have a 40-hour game and super-key systems are not coming online," he said. "I was pushing the game out the door going, 'Well, I hope it works'.... But we didn't have a lot of bugs in the game. We worked a lot in the end to try and figure that out, and lot of people kept saying, 'this is gonna be the worst, it's gonna crash all the time'. We were just constantly filled with this persistent doubt."

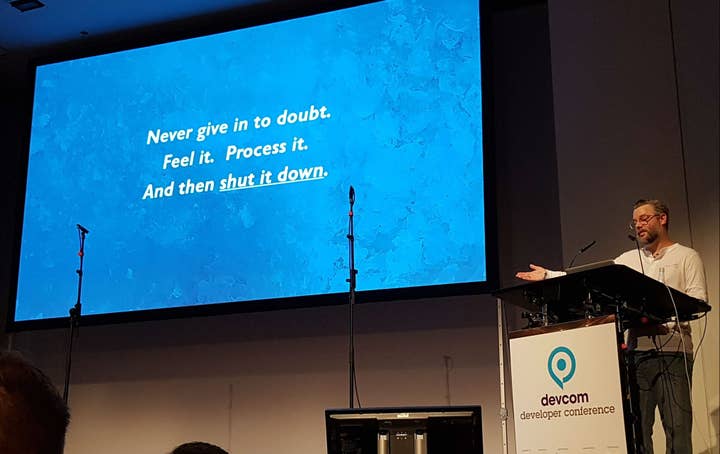

Ultimately, it was from doubt that Barlog derived the single most important lessons from God of War's difficult five-year journey. It was the doubt that flows naturally from embarking into new creative territory. And it was the doubt that is just as natural when surrounded by people that not only did Barlog respect, "but that I feared letting down."

"Never, ever give in to doubt," Barlog told the audience at the end of a frank and illuminating hour. "That is the worst thing that I had done periodically throughout. Initially, I tried to compartmentalise it, pretend that it didn't exist, but that also is stupid. It doesn't work.

"Feel it. Feel the doubt, process it, and then shut it out. And then move on.

"If you have somebody experiencing this [on your team], let them vent, let them tell you that they think the game sucks and you're going to screw everything up... Let them process it, and then say, 'Cool, we have three steps to get this done. Let's move on to step one, and ignore step two and three'... Just focus on the first thing, and get through that.

"I wanted to give up many times throughout this game. At the beginning I wanted to give up. At the end of the game there were some dark, dark points. And honestly, if it wasn't for Shannon Studstill, the GM of the studio, and Yuni Yang, the executive producer - they talked me off so many ledges throughout the production of this - I would not have continued. It was that dark and that difficult.

"The reason I ended up succeeding is because of this team, because of these people who cared so much about the individual aspect of the game that was theirs. They took ownership, and they pushed themselves farther beyond than they ever thought they would to get there."

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner for Devcom. We attended the show with assistance from the organiser.