Reaching a broader audience with games that have meaning

Ustwo's Ken Wong explains how being honest with art will enable game devs to tap into bigger audiences

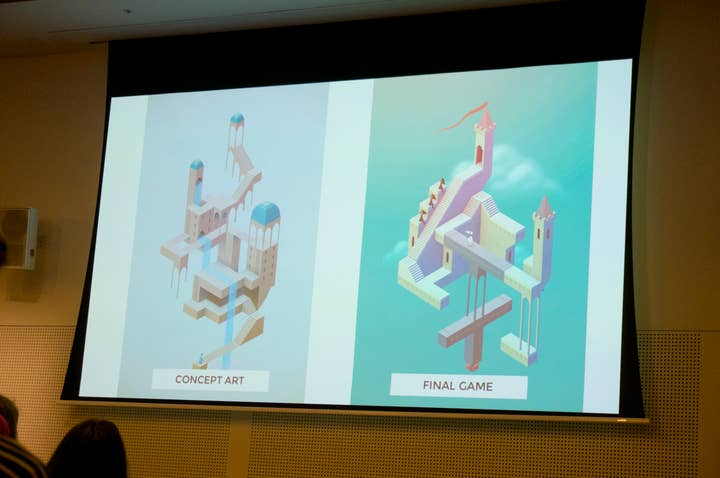

The eight-person Ustwo Games team made Monument Valley in ten months, pricing it on iOS and Android at the unusual $3.99 premium price point. It hit profitability in a week and quickly rose to number one on the paid app charts in 30 countries.

But for designer and lead artist Ken Wong, speaking at Game Connect Asia Pacific (GCAP), the best, most exciting thing is that they've been inundated with messages from non-gamers who say things like "I don't like games but I like Monument Valley" and "this is the first game I've ever finished." Some even admit to crying, or to the realization that games can be art.

The idea for Monument Valley came from art. Wong wanted to create a game out of M.C. Escher's Ascending and Descending lithograph print, simply about climbing impossible architecture. Then he considered Windosill, an iOS and Flash game in which your only reward is the interactivity of the environment.

"This was like a revelation to me," he said. "You can make a game that's just about interactions."

Monument Valley thus became a game about interactions that was rooted in Wong's passion for architecture and his fine art background. It was intended, from an early stage, to be different to other games. But his audience was himself, because then he could constantly ask himself if his ideas are fun and exciting rather than second guessing an imagined 35-45 year old woman or some other demographic.

"it's become too easy for us to say 'A button shoots' because of course that's what games are: you kill enemies. And consequently a lot of our role models in games are mass murderers"

Still, Ustwo aimed to keep the game short, so "normal people" can finish it. They wanted lead character Ida to give back to the environment, with what Wong calls "reverse Tomb Raider," instead of taking something away from it. And the distinct visual style owes something to a decision to keep the camera static so that Wong could best utilize his art skills for composition.

The point of Monument Valley is not to beat challenges or make decisions, Wong said. "It's just about Ida walking to the end, and you being along with her for the emotional and intellectual journey."

As seems to be a mini-theme of GCAP, Wong pushed for games to be more personal and less violent. There's a place for violence in games, he conceded, and a lot of games use it well. "But it's become too easy for us to say 'A button shoots' because of course that's what games are: you kill enemies. And consequently a lot of our role models in games are mass murderers."

How do developers avoid the trope? Just look at The Legend of Zelda, Wong suggested. Miyamoto's experience exploring caves and fields inspired that game's worlds and mechanics. Or consider Thatgamecompany's Jenova Chen, who was inspired to create Flower after he moved from the harsh urban landscape of Shanghai to the more natural environments of America. Wong also cited Zoe Quinn's Depression Quest and Minority Media's Papo & Yo as examples of "how to put more of ourselves into our games."

Wong believes that there's a huge untapped audience for such experiences, as evidenced by the success of those games and of premium mobile games like The Room, Sword and Sworcery, Year Walk, and, of course, Monument Valley.

Not many people know how to make premium mobile games well, Wong argued. Whereas the core of the mobile market is focused on copycat designs and riffs on already-popular games, high-quality premium mobile efforts need to be original and personal. And above all they must be honest, free from intrusive monetization or immersion-breaking bribes to give positive reviews for bonus gems.

Monument Valley balances artistic and commercial concerns through layers. It seduces players with its distinct visuals, Wong said, then grips them with the novel architecture-changing interactions, and then finally moves them with its core story and themes. It's an idea he took from the likes of Steven Spielberg and James Cameron, whose films find great commercial success while also retaining a core artistic depth. Spielberg injects his hits with themes such as the meaning of life, while Cameron's Terminator films are about what it means to be human, for instance.

Art is a form of communication, Wong concluded. If you're honest in your art and you make it memorable and easy to digest, you will reach a bigger, broader audience.