Meet the therapist making a 'therapeutic psychedelic trip through your smartphone'

A therapist and a science writer turn to games to revolutionise wellness apps

Hazel Gale has led quite the unique life.

After ten years working relentlessly as a boxer and kickboxer, Gale had burnt herself out and turned to therapy to get back into the ring. It worked, and she went on to win a number of big titles. But more than that, it changed her mindset and value system so entirely that she left boxing behind and started practicing as a therapist.

And now she's making games.

"I wrote a book about that journey, and also sharing the tools that I used along the way," Gale tells us. "And that's how Ellie [Elitsa Dermendzhiyska] found me, and we actually started working and writing a project. We published another book together. Ellie's a science writer and entrepreneur with a background in tech businesses, and she really nervously pitched this idea of making a game for mental health to me, thinking that I would laugh her off the phone.

"But what she didn't know is that I am games-obsessed. I was over the moon. The two of us got together, about two years ago, and did a mock-up on Facebook Messenger. It was the most basic thing. We didn't have any money, and we wanted to just see if people would actually buy into the idea of a fantasy story with therapeutic elements. We nervously bit our nails as people played it, expecting them to get turned off when it started to smack of therapy, but the opposite happened. They loved those bits. That's when we knew we were onto something."

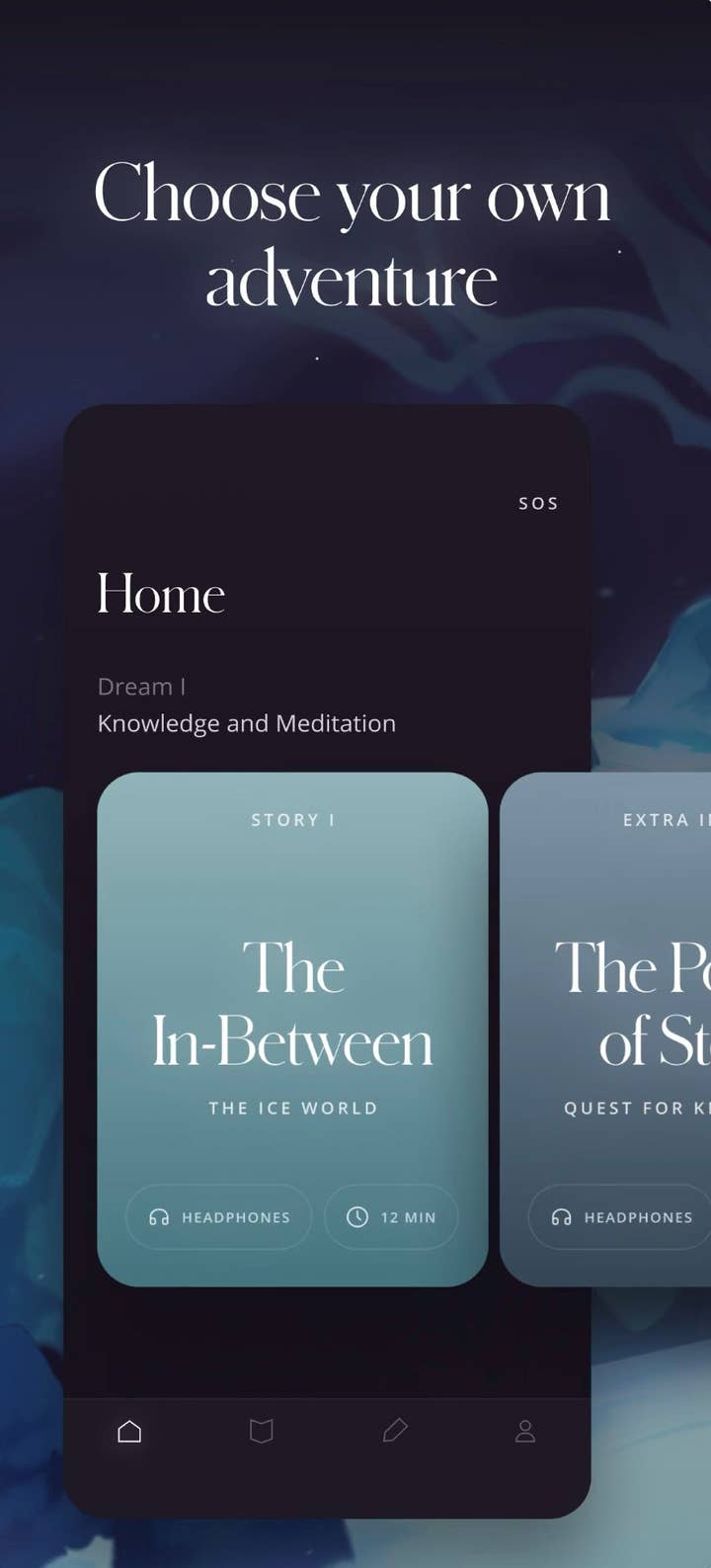

Betwixt is a game all about self-discovery and finding out more about yourself.

"It's us getting you to ask the right questions that get you to explore who you really are, what you really want, and a whole host of other things," Gale says. "The best description we've come up with so far is that it's a bit like taking a therapeutic psychedelic trip through your smartphone, but without any of the chemical complications.

"A lot of people are recognising that magic mushrooms and LSD have these incredible therapeutic benefits, and so they're taking these therapeutic journeys through them. It sounds amazing and, at the same time, really frightening. I'm not going to do it. But this idea of blurring the boundaries between reality and imagination is powerful. As a therapist, I think it's vital. If we don't get somebody's imagination and creativity awake during a therapy session, they don't get to see a new perspective, they don't get to try something different. So, we wanted to take that, but create a safe, comfortable version of it that's accessible to everybody by writing this fantasy story. Our users have been describing it as a cross between Lifeline, Myst, and Lord of the Rings."

Gale says Betwixt is an epic adventure that invites your real life into the game. Players are free to write into the app, and parts of that are fed back, while others are just for them.

"What it means is that they get this opportunity to co-create the world. We had two testers who played as friends, and they compared notes and found it fascinating that they'd both felt like they'd had a different journey. That's how it has to be. If it's going to have therapeutic benefit, it cannot prescribe a one-size-fits-all experience."

The game has been written by award-winning fantasy author Natalia Theodoridou. The story, which is still being developed, will feature 12 chapters, with a series of optional side-quests in-between. These extra quests feature psychoeducational information and guided meditations. There's also a journaling function, too.

The world itself is a metaphor. Players begin on a strange and bleak frozen world, which represents the numbing feeling before a person begins to tackle their problems. The player then befriends a voice, which asks increasingly challenging questions, and then the world begins to change. The ice melts, there's a flood, and you end up in a lost city with fantastical creatures and plant life.

"In order to save the city, they will need to meet their monster. The monster will be some issue that they have been struggling with, which we personify, and then they befriend. That's a big problem with the way we think about mental health, especially in the West. We think we need to slay our demons. We think we need to fight ourselves and get rid of the bad bits, which is the most counter-intuitive and counter-productive way of dealing with anything. If you try to fight yourself, you lose, which I learned in the boxing ring in a very painful way. So, they meet their monster, befriend their monster, and save the city."

"If you try to fight yourself, you lose, which I learned in the boxing ring in a very painful way. So, they meet their monster, befriend their monster, and save the city"

Betwixt draws on real therapeutic science, including cognitive behavioural therapy, transactional analysis and positive psychology. There are traditional counselling methods, but also elements of cognitive hypnotherapy, mindfulness meditation, and expressive writing.

But one of the main elements of the game is around the theory of narrative identity, and the concept of seeing yourself as the hero of your own story, rather than the victim of the world that happens to you.

"You're a character in the story. And as you begin to build autonomy by making your choices and answering questions, you level up to hero, which is when you try to find your monster. But of course, you don't win when you fight your monster. So, you have to look at it in a different way, and that's when you start to explore what the monster really is, befriend the monster, and then eventually own it.

"That's when you become the author of your own story. You go through these levels: character, hero, author. It's about feeling in control of your life, taking control of things you can control, which are your perspectives, thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, not other people's opinions and results."

The other main element of the game is around the idea of self-distancing.

"Self-distancing is the simple act of taking a step back and viewing yourself and your life from a healthy, objective perspective. It's enormously powerful, but not something we do automatically.

"Seeing yourself go through this other world... that's automatically self-distancing. And then there are some quite strict self-distancing moments. The flood, for example, represents the emotion you're struggling with, and it turns into this enormous wave that threatens to crash down upon you. And you realise that if you keep standing there, the wave will, at some point, overwhelm you. But the voice guides you in floating up above the wave and looking from above. At which point, the wave looks much smaller and less threatening, and then they view a situation from that angle and write about it.

"Self-distancing comes up often. It's just such a cool, simple thing. You can do it just by talking to yourself in the second person. It's as simple as that."

Betwixt isn't designed for people with a diagnosis. This isn't a game that deals with depression or OCD. Instead, it's about working through our individual anxieties or issues.

And Gale believes by making an actual therapy game, rather than simply going down the gamification route, it can solve many of the issues she's experienced with mental health apps.

"There are an enormous number of apps out there that have really great advice, but even though they have great results in developer-led trials, in the wild they don't work because people don't stick with them," she says.

"Mental health apps and programs have extremely poor retention, only 3-4%. It's too hard for the people to stick with something that feels dry. Also, there are a lot of chatbot mental health apps out there that feel a little patronising, or a little blasé. Sometimes people are getting really counter-productive answers from AI, because it's not quite there yet.

"There are lots of apps out there that try to gamify mental health, but it does not go down well. People find it trivialising and inappropriate."

"There is a need to change the way mental health is happening online. Because on top of the fact that lots of people can't afford therapy, the demand is now massive. In the US, before COVID, 11% of adults reported problems with mental health, anxiety, and depression. Now it's 40%, and it's expected to get higher. In the UK, over COVID, the demand for mental health resources has increased to three times the capacity of the NHS. So, unless we find other ways of having those conversations, we're fucked."

She continues: "One of the reasons we started this was because Ellie was researching mental health for about five years, and she was asking people about the apps they were using, and they'd all tell her about these great programmes. And then she'd say, 'How often do you use them?' And they'd say, 'Well, actually, I don't.' So it's like, 'Well, what do you do instead?' And so many of them said, 'Well, if I'm feeling bad, I play video games. I escape to fantasy worlds to feel better.' So, that's where it started.

"There's this Terry Pratchett quote: 'It matters not what you escape from, but where you escape to.' What we wanted to do with this game was create an escape that actually had a point to it, rather than just being escapism."

Gale says that games align well with basic therapeutic teachings.

"The growth mindset, for example, is something that any gamer can overcome extremely quickly, because they have to. You have to fail and then retry in games as standard, which is something that we don't do much in real life, because we all fail the first time and then think, 'Well, obviously I'm not good at that,' and go and find something else to fail at."

She adds: "As a therapist, a pretty common misconception from people is that they don't consider themselves creative, or incapable of visualising. Well, some actually can't. But two people who said they were convinced they couldn't visualise sent us excited feedback that they'd been playing the game, and for the first time ever, had this really clear picture in their mind of the space they were in.

"That's down to our writer, of course, who's painted this beautiful picture. But, getting people to bring their imaginations into the space, and giving them full licence to completely go with that, is a vital part of therapeutic change, and gaming is perfect for that. It's much better than standard art therapy routes, which I've looked at. My book encouraged people to draw their monsters, but for a lot of people there was a barrier: 'Well, I can't draw. I'm not going to draw it. It would look crap.'"

Of course, unlike a game, players can't 'win' at mental health. Which is why the story element is so crucial, Gale concludes.

"There are lots of apps out there that try to gamify mental health, but it does not go down well.

"People find it trivialising. They find it inappropriate, and that's totally right. If you're trying to win at mental health, you're getting something wrong. It's not going to work. But we've been learning through story since we were able to talk. And I don't mean individually, I mean the human race. Storytelling has been the way of conveying meaning ever since cave drawings and chats around campfires. And that's what games can do really effectively."