Facebook enters cloud streaming with free-to-play mobile games, playable ads

Jason Rubin explains the company's plans to make the bottom line work, and how he expects streaming to change play patterns

Facebook today announced it is getting into on-demand game streaming, but VP of Play Jason Rubin tells GamesIndustry.biz it's tackling the tech in a different way from other companies like Microsoft and Google.

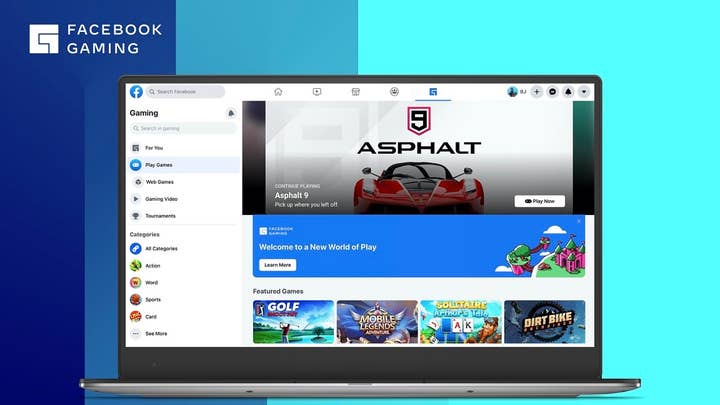

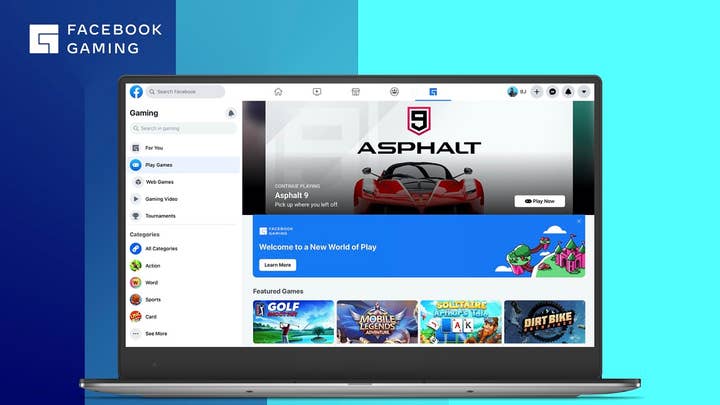

First, there's the type of games that will be streamed. Unlike Xbox Game Pass or Google Stadia, Facebook isn't offering AAA or indie console and PC titles. Instead, it will let people visiting Facebook through a browser or using the Facebook app on Android to stream free-to-play mobile games.

The company is also starting its streaming effort with just five titles: Asphalt 9: Legends, PGA Tour Golf Shootout, Solitaire: Arthur's Tale, WWE Supercard, and Mobile Legends: Adventure.

That selection was chosen in part because those titles have gameplay that can accommodate a bit of latency, but Facebook intends to branch out next year into action and adventure titles, and Rubin says the long-term picture could include all types of games.

The business model is also vastly different from other cloud-streaming offerings. There's no subscription model and in light of the free-to-play nature of the games, no way to sell individual titles up front. Instead, Facebook will take a typical platform holder 30% cut of revenues for in-app purchases made in games streamed through Facebook on a browser. For games streamed through the Facebook app on Android, the platform holder cut will go entirely to Google.

We point out that free-to-play has not been a focus of other game streaming outfits, since footing the bill for non-paying players to stream makes them a more pronounced drain on the bottom line. He concedes it might be an odd pairing for some streaming services, but says Facebook is in a position to make it profitable.

"Most free-to-play developers find people through advertisement, and they find people through advertisement, in a majority, on Facebook," Rubin says. "It's a great place to find people because people go there 20 times a day, in general, to check in. By allowing these cloud-playable games and cloud-playable ads on Facebook, we greatly reduce the funnel from someone seeing an ad to an 'install.'"

The streaming process makes it simpler for developers to create and serve up playable ads, Rubin says, and the ability to jump straight into playing the games properly after seeing a Facebook ad instead of having to switch over to an app store, logging in, and browsing reviews and videos on the store page to see if they actually want it. Instead they can quickly jump to streaming the game.

"We think that's a really powerful ecosystem development because it cuts the funnel at the top without getting in the way of the ecosystem working however the consumer wants it to work, whether that's with a local download or continuing to stream," Rubin says.

"We believe that based on the increased efficacy of the advertising, we can cover those costs [of streaming free-to-play games] and be profitable"

Rubin notes that if a streaming player likes a game so much they want to just download it and play that way, they can do so while transferring their progress to the downloaded version of the game. But if a player who starts a game through streaming jumps to a downloaded version of the game on iOS or Android, Facebook would get no cut of revenues generated from those versions of the game.

As for how Facebook makes this scenario make business sense from streaming free-to-play games to letting players cut them out of the revenue chain, Rubin says, "We believe that based on the increased efficacy of the advertising, we can cover those costs and be profitable. And on top of that, we get the added benefit that the community of gamers that's ever-expanding is coming to Facebook when they think about gaming."

He adds, "Remember, we're an ad platform. So they probably found that game through an ad, or through their friends, through community and all the stuff we do on Facebook."

300 million people play games on Facebook each month, Rubin says, but more than 700 million go to Facebook "to engage in gaming," when you include those who watch streamers on Facebook Gaming or take part in game-related discussion groups.

"We think there's a huge opportunity to expand the number of players on our platform by offering the type of game that has not currently been available to those users because of the limitations of HTML5 and other technologies," he says.

One thing that Facebook actually has in common with other game streaming options is that it isn't officially supported on iOS. Rubin says that's a result of "rules and technology" that are blocking the company, and not any kind of reluctance to turn the 30% share of revenues over to Apple.

"That's not the reason we're not bringing it to the platform," he says. "It's more that the rules make it a bad consumer experience and it's really confusing and inoptimal for us to do so."

This isn't the first time Apple and Facebook have been at odds over games. Last month, Facebook launched its Facebook Gaming app on iOS after months of repeated rejections, but only after it stripped the app of all gameplay functionality.

However, Facebook is examining alternatives to bring its streaming games offering to iOS users.

That's not the only group of Facebook users who will have to wait to try out streaming on the platform. The company said it is only starting to introduce streaming in parts of the US this week, "initially available across California, Texas and Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states including, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Washington, D.C., Virginia and West Virginia."

"You would expect if you were given 10 times as many flavors [of ice cream] to try with a spoon, you would try more, but select the same amount on average to eat"

Facebook said it will add to those areas as it builds out necessary infrastructure to scale the operation wider.

The company has actually been beta testing the service in a number of regions lately, bringing in up to 200,000 players per week. While Rubin says it's too early to get concrete insights into just how streaming will impact player behavior in free-to-play games, he's willing to share his expectations.

"My guess would be time spent per user will be less on average. The reason for that is so many people can try more stuff quickly, but over time, value of users obtained on Facebook will be higher. You would expect if you were given 10 times as many flavors [of ice cream] to try with a spoon, you would try more, but select the same amount on average to eat."

He also believes that streaming may help bring lapsed players back if they hear about new content for a game and don't want to download multiple gigabytes of data.

We ask Rubin what Facebook is doing to address concerns about the environmental impact and energy consumption of its game streaming.

"That's a good question," Rubin says before acknowledging he's not aware of anything specific the company is doing on that issue. "What I would say is this. Anything Facebook does is covered by its general policies. So its general target to be of a certain carbon neutrality or not would cover this, because it is a Facebook process."

"I'm not dismissing in any way people's beliefs and their views of Facebook, but I am saying that we're very cognizant of the things we've done in the past and the way people view us"

Facebook's corporate sustainability plan says it will achieve net zero green house gas emissions from its direct emissions and those related to electricity purchased by the company this year. Indirect emissions caused by people using its platforms like Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger made up about 95% of Facebook's carbon footprint in 2019, and the company has pledged to hit carbon neutrality including those emissions by 2030.

Finally, we ask Rubin what he would say to those skeptical of Facebook's ambitions in game streaming given the company's track record on privacy, its decision to mandate Oculus users have a Facebook account, or concerns about the impact of cloud streaming on the games industry in general.

"Facebook has definitely made mistakes, and we've admitted them," Rubin says. "I think if you go back and look at some of [Facebook CEO] Mark [Zuckerberg]'s statements in the recent past, that's pretty obvious."

He says the company is working to mitigate some of those concerns and gives the new player name option as an example. While Facebook itself still has a real name policy for users, those playing games will be able to choose a pseudonym to appear as in-game, as a way to potentially cut down on harassment.

"I'm not dismissing in any way people's beliefs and their views of Facebook, but I am saying that we're very cognizant of the things we've done in the past and the way people view us. And in this specific case, we're trying to do as much as we can to get ahead of that and do the right thing."