Duplication or innovation? How games become genres

Earthbound Games' Colin Anderson reflects on the rise of the FPS, the sandbox RPG and more

In London on a bitterly cold, early-Spring day in 1966, Eric Clapton plugged his Gibson guitar into a Marshall amplifier, waited for the recording engineer to signal the tape was rolling and began playing the blues.

It was the session where he recorded the now famous 'Blues Breakers' album with John Mayall -- a record that would change the face of popular music and kick-start an entirely new musical genre that what would eventually become known as British Electric Blues.

While many artists had recorded electric blues records before, Blues Breakers was the first to attract the attention of mainstream audiences. As a result, it paved the way for a host of later bands such as Fleetwood Mac, Ten Years After, and Jethro Tull to bring their music to the masses.

There were two critical things that turned Blues Breakers from just another electric blues record into the one credited with inventing a whole new genre: first, it validated the audience's appetite for this new kind of music, and second, it inspired other bands to build and experiment with the album's basic blueprint.

Game genres forged by creativity

Like music, there are also many genres within video games. Like British Electric Blues, game genres were all started by a talented and inspired group of creative people determined to push themselves and their medium into new areas.

I've been making games long enough to witness entire new game genres emerge during that time. I remember playing Doom for the first time, astonished at how 'real' it felt. I then watched as a whole host of games like Duke Nukem, and Dark Forces emerged, building on the blueprint Doom laid down only to became known, somewhat disparagingly, as "Doom Clones". However, players eventually got over that and realised these games weren't simply trying to clone Doom -- they were trying to expand the archetype Doom had defined and so the less pejorative "FPS" tag took over.

"It can be quite tricky to spot the difference between a title that's legitimately trying to contribute to establishing a new genre and others cynically cashing in"

Similarly, I remember being utterly charmed by the originality of Parappa The Rappa. The rest of the world then 'cloned" the concept with Dance Dance Revolution, Guitar Freaks, Vib-Ribbon, Rez, and the others that eventually came to define the Rhythm Action genre.

As much as I loved playing Tetris and Panel de Pon, I'm genuinely glad that others took inspiration from the basic formula to create Bejewelled, Jewel Quest, and their ilk later. Those games that followed all gave me enjoyment and the world of gaming would be less for losing any of them. In each case I fully recognise and respect that initial spark of genius but I'm just as grateful that it ignited the hearts and minds of others who then used it to offer something of their own.

The trouble for both players and developers alike is that it can actually be quite tricky to spot the difference between a title that's legitimately trying to contribute to establishing a new genre and others cynically cashing in. It's mostly time and audience reactions that separate them and I've come to accept that a healthy dose of scepticism is a necessary part of the process as original games go on to seed entire genres. I now recognise that our industry would never have gained the FPS genre without moving through the era of "Doom Clones".

Creating Sandbox

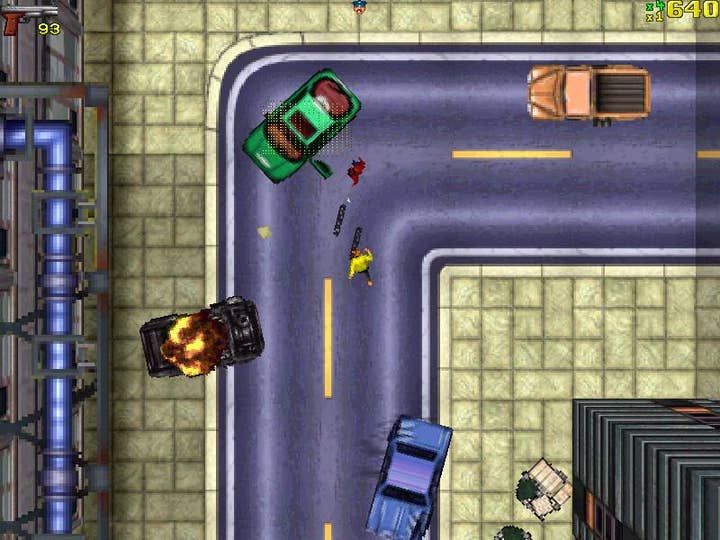

I've been afforded a privileged perspective on this during my career as I had a front-row seat during the creation of an entirely new genre when I worked on Grand Theft Auto's first three iterations. I witnessed first-hand how its core "wouldn't it be cool if you could go anywhere in the city and steal any vehicle?" concept eventually went on to define sandbox games. While we were making GTA, nobody in the development team used the term "sandbox". To us, we were always just making the best game we could at the time rather than starting a genre -- yet that's what happened.

"It might seem like GTA was always destined to be the game that defined sandbox gaming, but from an internal perspective things felt very different"

I first noticed the term when I began to read articles discussing "GTA Clones" like Driver and Wheelman (which I loved!). This eventually moved into the more respectable sounding "Sandbox RPG" genre and has since produced many more games that I've enjoyed playing such as Saints Row, Just Cause, Assassin's Creed, and Red Dead Redemption. Personally, I'm really glad that others felt inspired to explore the blueprint GTA defined because my own gaming experience has been much the richer for it.

From an external perspective it might seem like Grand Theft Auto was always destined to be the game that defined sandbox gaming, but from an internal perspective things felt very different. Even though we didn't use the term ourselves, sandbox gaming as a concept was definitely 'in the air' at DMA Design back in the mid-1990s and most of the games the company was working on at the time had a similar sense of 'go anywhere, do anything' to them.

Grand Theft Auto is undoubtedly the most famous of them but Body Harvest, Space Station Silicon Valley, and Wild Metal Country were all in development at the same time as GTA, and each blended slightly different flavours from the same well of inspiration.

Space Station Silicon Valley was the weirdest manifestation of DMA's obsession with open-world games (as I think we referred to the idea at the time). The player took on the role of Evo, a robot reduced to its microprocessor that could leap between any of the exotic robotic inhabitants of Space Station SV in their quest to fix the station's controls before it crashed into Earth.

Body Harvest appears to share the most similarities to GTA at first glance -- the player in their role as the genetically engineered soldier Adam Drake can go anywhere within the open-world and drive any vehicle. But instead of stealing any vehicle they want for profit or the-hell-of-it they instead 'commandeer' any vehicle they want in service to fighting off the alien bugs intent of harvesting the population of Earth.

"A 'Something Clone' is just a necessary, if slightly uncomfortable, step to helping turn great games that defined an archetype into new genres"

Wild Metal Country again retained the open-world format, but this time without the ability for the player to step into any vehicle as they roamed the three planets of the Theric system, destroying the marauding AI-controlled tanks intent on taking them over. While it lacked the 'do anything' part of the 'go anywhere, do anything' formula that GTA, Silicon Valley, and Body Harvest used it instead pioneered the most advanced physics and AI systems DMA had created up to that point.

In slightly different circumstances any of these games might have gone on to define the Sandbox RPG genre, and yet none of them did. But then neither did GTA 1 or 2 really, despite how popular and inspirational they were in their own ways. From the perspective I had as one of very few people who worked across all of these teams in my role as audio director at DMA Design, I can appreciate that they each provided DMA with valuable experience and important lessons that were all required for the company to deliver its seminal sandbox RPG in GTA III.

That's because GTA3 was created by fusing GTA1's well-proven game template with the most important lessons each of these other teams had discovered during their own development adventures: the technical 3D and production expertise of the Silicon Valley team, the open-world level design lessons from Body Harvest's encounters with Nintendo, and the real-world physics and AI behaviours from Wild Metal Country. No individual development team at DMA contained all these elements in-and-of themselves, but each of them brought important skills and hard-won experience that eventually allowed GTA III to happen when they all came together.

Weathering criticism

Recently, I've once again been working with some of the original members of DMA's Wild Metal Country team whose love of tanks, physics, and AI appears altogether undiminished despite the intervening 20 years or so. This time I'm witnessing the whole 'genre debate' play out again, but this time from the other side after Earthbound Games announced its upcoming release of Axiom Soccer.

On the surface it's set in a sports arena and focuses on vehicles and footballs, so inevitably it has attracted its fair share of dismissive-wrath from the more judgemental sections of gamerdom for being "nothing more than a Rocket League Clone". Of course, that's not how any of the team see it, because many of its members have both witnessed and participated in the creation of game genres, so we're better placed than many to appreciate the truth is a little more nuanced than that.

While Axiom Soccer is unashamedly inspired by Rocket League's "vehicles + football" archetype, at its core it is as different as it is similar. If Rocket League was "Mario Kart + Football" then Axiom Soccer is "Gears of War + Football". One is primarily a driving game, while the other is primarily a shooting game. That said, they are both wrapped within the familiar environment of a soccer pitch and put in service of scoring goals, rather than running people over or blowing heads off, so comparisons are certainly not unreasonable.

As a younger developer I might have felt the need to defend any game I was involved with from accusations of being an "Anything Clone". However, from the broader perspective I've accumulated during my career after seeing the issue from so many angles I've come to appreciate that "Something Clone" is just a necessary, if slightly uncomfortable, step games must go through if they aspire to help turn great games that defined an archetype into new genres.

Colin Anderson is commercial director at Axiom Soccer developer Earthbound Games. Among his numerous previous positions, he was audio designer, then manager, at DMA Design