Can a developer succeed making games for itself?

Ex-BioShock devs Jordan Thomas and Stephen Alexander might find the answer with their new studio, Question

As developers on the BioShock series at Irrational Games, Jordan Thomas and Stephen Alexander spent years trying to make games that would appeal to the largest possible audience. Now the duo have co-founded their own studio, Question, and are making something unashamedly niche and personal, a high concept game about the perils of AAA game development.

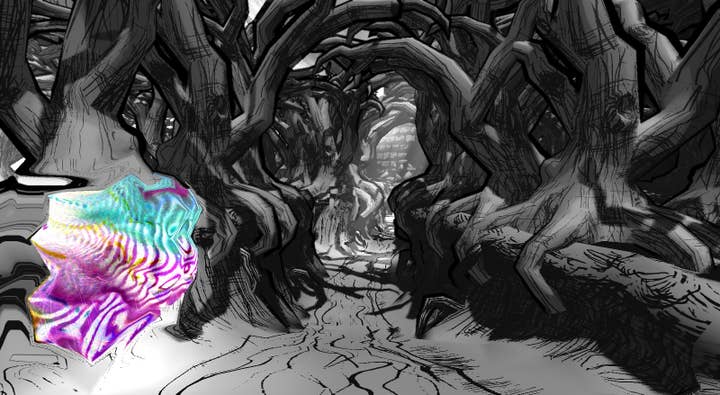

The Magic Circle is about a piece of highly anticipated vaporware (also called The Magic Circle), an ambitious project that has spent decades in development purgatory as the highly touted auteur at the helm has struggled with the game's myriad problems and unfulfilled promises. As players make their way through an incomplete build of the game, they get to see how and why the fictitious developers have failed. And by taking code from various AI in the game world and recombining them in creative ways, they can even fix some of those issues along the way.

"It's not autobiographical, but I felt like unless the worst of it was something I could be accused of, in some measure, it'd just be mean spirited and/or didactic."

Jordan Thomas

It's a game about making games, about the progression from auteur-worshipping fan to eyes-wide-open developer, informed heavily by the creators' own personal experiences. While it would be easy to read the premise or the promises on the game's superficially absurd website and see it all as a comment on Irrational Games head Ken Levine, Thomas said The Magic Circle's narrative has been informed by every project and team member he's worked with, not to mention his own experience wearing the auteur pants on BioShock 2 at 2K Marin.

"Directing BioShock 2 definitely gave me a taste of all the--almost necessary, initially--overconfidence and creeping doubt/screaming panic that I think people at all tiers of a creative hiearchy feel," Thomas told GamesIndustry International. "And definitely many of my mistakes as a leader are touched on in the script, although they're exaggerated hugely in The Magic Circle. It's not autobiographical, but I felt like unless the worst of it was something I could be accused of, in some measure, it'd just be mean spirited and/or didactic."

Although it's not a perfect match for tone, Thomas points to Tina Fey's 30 Rock, where much of TV series' humor emerged from her own experiences running Saturday Night Live, with the laughs often coming at her own expense.

"Our biggest fear is that it would come across as bitter, because we definitely don't feel that," Alexander said. "As I read what Jordan is writing, that's a litmus test I put it through. Because sometimes the easy joke is a little meaner. And then it doesn't feel as true because that's not where we're coming from. As the script has evolved, it's become more and more a mix of empathy and send-up. Because obviously, we're talking about ourselves as much as anything. We realize that we've been paralyzed by many of the same things sent up in the game as we are making it, which is meta upon meta upon meta."

"That said, nobody comes away clean," Thomas added. "It would be boring writing if it weren't occasionally uncomfortable, I think. My career started out as a player. This whole thing is kind of about this journey. Whether or not it ends in you becoming a game designer... It's almost like saying, 'Hey, are you sure?' You start out as an auteur worshipper. You start out thinking, 'Wow, they made this out of whole cloth and it is brilliant and unassailable and holy crap. And I have some problems, but wow, they're still real smart.'

"But when you start to make anything, creating something of your own, you realize it is fraught with bone-breaking stumbles and paralyzing self-doubt. Pick your poison, but that humanizes the creator figure. My hope is that the love in the script comes from the fact that this may be where the creator myth meets truth. And maybe that's ugly, but it's also sympathetic, I think."

In short, it's not an idea that boils down to a neat elevator pitch or was designed to test well with focus groups. When asked who the game is for, Thomas pauses for a second, then says the target audience is a venn diagram slice covering "people who actually make games and who might be good promoters for us if they like it, people who play games but think, 'I can do better than that,' and people who just want to see games sent up." Alexander suggests the game is actually for people who are passionate about games and the process of making them, perhaps who love games but hate the industry.

"I know to survive, we need to be aware of our audience. But I'm not a fan of deciding what you're going to make based on that."

Stephen Alexander

And of course, they are making the game for themselves. But as admirable as the artistic drive to make a game for one's own edification may be, Thomas and Alexander are still creating a business and a product. They need The Magic Circle to sell in an indie marketplace increasingly crowded by competitors.

"I know to survive, we need to be aware of our audience," Alexander said. "But I'm not a fan of deciding what you're going to make based on that. I just wanted to know that I was excited about it, because I knew I'd be devoting several years of my life to this."

That's a big part of the reason why The Magic Circle isn't being crowdfunded. Alexander and Thomas said they're making the game with money scrimped and saved through their past jobs, consulting work, and support from their families. That gives them the leeway to not only make the sort of game they want, but to do so without fear of running afoul of other people's expectations. On the decision to forego a Kickstarter, Thomas said, "We put ourselves in a situation where we wouldn't have to ask for people to sign a contract they didn't understand yet."

All this isn't to say Question is being reckless in making its first game. Speaking with Thomas and Alexander, it's clear the pair actually have given consideration to many aspects of their business; they just haven't let that dictate their creative output. Take the marketing plan, for example. Both developers have taken to heart the hustle needed to get people talking about The Magic Circle. It's a concern they've been doing their best to ignore until recently.

"I am very worried, of course, that the quality and proliferation of even ex-BioShock indies, and indies in general, has risen significantly, and it's only getting scarier."

Jordan Thomas

"There's a certain amount of blinders you have to put on to make sure that you can make the thing, with the knowledge that at some point they're going to have to come off, probably sooner than you want so that you can get the word out in time for it to matter," Alexander said.

Thomas agreed, but reasoned, "We still believe that if we have to divide our time, it's better to make the product speak for itself as much as possible, so we focus on making it first, and promoting it sort of as and when."

One thing working in Question's favor is the game's individuality. Thomas said he's "not even a little bit" worried that The Magic Circle is going to wind up being too similar to anything else on the market.

"I think we're in our own little freaky corner, and I'm satisfied with that," Thomas said. "But I am very worried, of course, that the quality and proliferation of even ex-BioShock indies, and indies in general, has risen significantly, and it's only getting scarier."

As daunting as the quality of competition might be, it, like every other concern mentioned above, isn't scary enough to get Thomas and Alexander to actually change their game in response.

"Perhaps just as contrast to years of asking, 'Yeah, but what about the couch gamer?,' there was this desire to make something that above all, we would love and come what may," Thomas said.