Are there lines games shouldn't cross?

Can a dev go too far with violence? What about moral responsibility? Laws aren't the answer, but what is? Rami Ismail, Warren Spector and more discuss

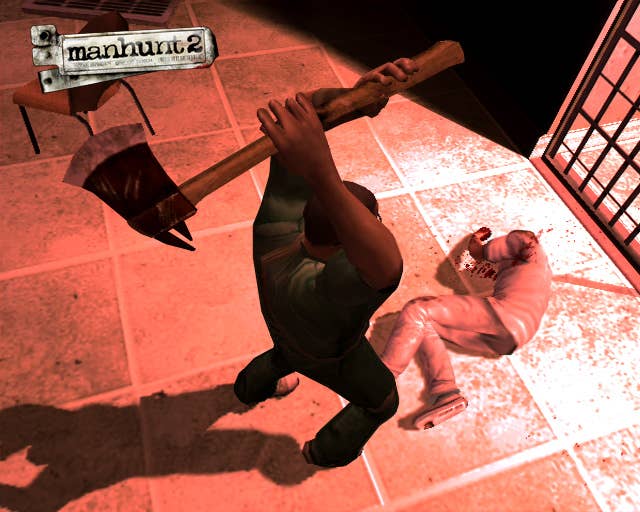

Video game violence has been in the spotlight for over two decades now. When Senator Joe Lieberman chaired a subcommittee in 1993 after seeing the violence in Mortal Kombat, the mainstream media started paying close attention. And just five months later, the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) was born and assigned Mortal Kombat an "M" for Mature rating. This was undoubtedly a good thing. In the years following, the board continued to tweak its ratings and in combination with retail partners it's become one of the best systems for keeping inappropriate content from our youth (as ranked by the FTC).

However, in the last 5-10 years that I've attended E3 and other trade shows, I've seen wave after wave of intensely violent content. In previous roundtables with my GamesIndustry.biz staff, I've referred to it as the Michael Bay-ification of the games business. There's a lot of eye candy, lots of fighting and plenty of explosions; but as veteran designer Sid Meier pointed out, the industry doesn't need to push that sort of content anymore. "I think we got people's attention. We can make good games now," he said.

"Only the developers' conscience should define what type of game they want to make, and its level of cruelty, indecency and moral corruption"

Adrian Chmielarz

I'm not suggesting that the industry abandon this type of content, but I am wondering whether developers actively think about what lines are okay to cross. It's especially relevant considering that in the last week or so a trailer for a brutally violent game - effectively nothing more than a mass murder simulator imitating the worst shootings in America - made the rounds on the internet. Some of my peers on other publications unfortunately gave them exactly what they wanted: plenty of press in the form of critiques, trailer embedding and interviews. I won't give them that gratification, but I did speak with developers about how much violence is actually acceptable in today's games.

"I think that yes, there are lines that game developers should not cross," said The Astronauts' Adrian Chmielarz, former creative director at People Can Fly. "On the other hand, no, these lines should not be defined by law. In other words, only the developers' conscience should define what type of game they want to make, and its level of cruelty, indecency and moral corruption."

Deus Ex and Epic Mickey creator Warren Spector is of the mind that even if he finds something completely objectionable he wouldn't attempt to tell other developers what lines they can or can't cross.

"I'd never want to mandate where the lines are but there are certainly lines for me. The fact is, I think of games as a form of communication - as an art form - with all the first amendment rights of any more traditional medium of expression. Any limitation is anathema. We just have to make sure people know what they're getting into before they pay for or begin playing a game," said Spector, who's now the Director of the Denius-Sams Gaming Academy at the University of Texas at Austin.

"That's where our solid ratings system comes in. Having said that, there are lines of good taste I WISH developers wouldn't cross, but personal opinion is never an excuse for setting any kind of public policy. I'll continue to call out developers who cross the line of good taste, but it'll just be the opinion of one man, not a proscription for an entire medium."

Vlambeer's Rami Ismail pointed out the power of games as a medium. If a developer can think of it, it most likely can be made - but just because something can be made doesn't mean it should be. "I think it's important to realize that there are no lines that developers can't cross as long as a project is feasible, and whether they should is obviously up for discussion," he said.

"If you're executing innocent civilians that are begging for their lives because that is your intended goal, without any lessons to be learned... then I feel that the creators failed to make anything noteworthy"

Rami Ismail

Indeed, that's the hard part to figure out. While it's technically possible to animate some brutally violent action in great detail, does it need to be included? Some would say yes, some would say no.

"It's justified if there is a strong thematic, narrative or mechanical reason to offer objectionable or offensive content, and if it's done in an appropriate and considerate way," noted Ismail. "There's a big difference between 'just throwing in Nazi's' or 'I guess some sort of sexual violence' and 'here's a terrible thing that fits this context in every conceivable way'.

"Games have a long tendency of justifying violence through ridiculous means. We happily accept that we're killing faceless 'bad people' when a nuke launches in the first part of the third act of a first person shooter. We feel justified for shooting at threats to the West, but we're outraged when you shoot at civilians. I think that difference is justified, because the ludo-narrative context of it changes. If you're executing innocent civilians that are begging for their lives because that is your intended goal, without any lessons to be learned beyond what execution animations exist, without offering a useful perspective to terrible events like these, then I feel that the creators failed to make anything noteworthy."

Devolver Digital's Graeme Struthers largely agrees: "In general, my view on content tends to come back toward the artist and what story they are seeking to tell. For example, If the project is holding a mirror up to society and challenging the audience, I think that can be a good thing. This War of Mine is such a strong and positive example of that. Good entertainment can tackle difficult and even controversial subject matter.

"Seeking to be controversial for the sake of it should always be challenged and I figure that fans and games media are savvy enough to see those things when they come along."

While extreme violence may reflect poorly on the medium in the mainstream, Spector noted that no developer should ever feel that he or she has to censor a game's content to fit some pre-approved mold.

"There are obviously cases where satire comes into play and others where content that's objectionable to some is portrayed in the context of making a statement of some kind. Still, it seems patently obvious that a lot of game content does damage to the medium in the public eye - plenty of games confirm the biases of our most outspoken critics. But despite that, we have to defend ourselves by reminding people of our ratings system and by citing all the games that AREN'T objectionable or potentially offensive. Censoring ourselves isn't the answer," he said.

Perhaps the bigger question then is whether game developers have some moral responsibility to the players. There's no proof that violent games can lead directly to senseless acts in real life, but if a certain individual is already dealing with some pathological psychosis, it's easy to see how an extremely graphic video game could act as a trigger.

Developers seem to be torn on the question of morality in games, however. Ismail is in the camp that believes developers should own up to that responsibility.

"Wouldn't it be a sad medium if we didn't?" he questioned. "We claim that games are impactful, that they have meaning and purpose. We create worlds from bare code, from data and models and pixel and sound and music - worlds that adhere to our every whim, our every intent - and then we get to place players in there and allow and deny them certain interactions. We work in a medium in which our users don't talk about the characters, but identify to a point where they talk about what 'they' did, instead of what 'a character' did.

"This is the most personal and exciting medium in the world, and we have the ability to create things for which we are responsible and accountable - things that reflect ourselves and our views and interests. Making anything less feels like a waste of potential of this medium."

"Players will vote with their dollars, inevitably, and all we can hope for is that their sense of good taste and common sense comes into play as they make their purchasing decisions"

Warren Spector

Chmielarz agreed. "Yes, of course. We create things to affect people, so how could we not?" he said. "However, to be clear, I don't hold creators responsible for triggering psychotic behaviors. Psychopaths will always find a trigger - today it may be a video game, but a hundred years ago it was a poem, and five hundred years ago it was some other pretext. Video games (or other art forms) don't create psychopaths, video games may only reveal psychopaths."

Spector, on the other hand, said he didn't feel that developers should feel morally responsible, even though he has a strong aversion to extremely violent games.

"Again, there's so much personal taste involved in the creation of game content it'd be hard to say when a game crosses some line where moral responsibility comes into play. I can wish all day that developers would stop making games that 'go too far' but all I can do is express that wish loudly enough and publicly enough that game creators feel a little ashamed of themselves and maybe change the way they think about the medium," he remarked.

Ultimately, the content in the games of the future will be dictated by everyone in the gaming community, including players, press, and developers. As Ismail pointed out, "I think the press should criticize, the devs should discuss and the players should decide whether they're interested or not based on the press and devs."

Spector added, "I think the primary response from press and developers has to be adequate communication. People - players - have to know what they're getting into before they get into something. Players will vote with their dollars, inevitably, and all we can hope for is that their sense of good taste and common sense comes into play as they make their purchasing decisions."

Discussing what type of content makes it into our video games is a healthy thing for the medium as a whole. You'd be surprised, however, how many developers GamesIndustry.biz reached out to who simply declined to take part in the discussion. If video games are to continue to evolve and mature, then discussion is key.

"Do not avoid the subject," said Chmielarz. "We make video games, and one branch of video games is slowly evolving into holodeck experiences. In a few years we will have virtual reality sims that will give an uncanny illusion of real life experiences. Avoiding difficult subjects that help us get ready for that would be a mistake."