Are comics a cautionary tale for game makers?

Maus creator Art Spiegelman describes the "Faustian deal" comics made and the danger of cultural exaltation

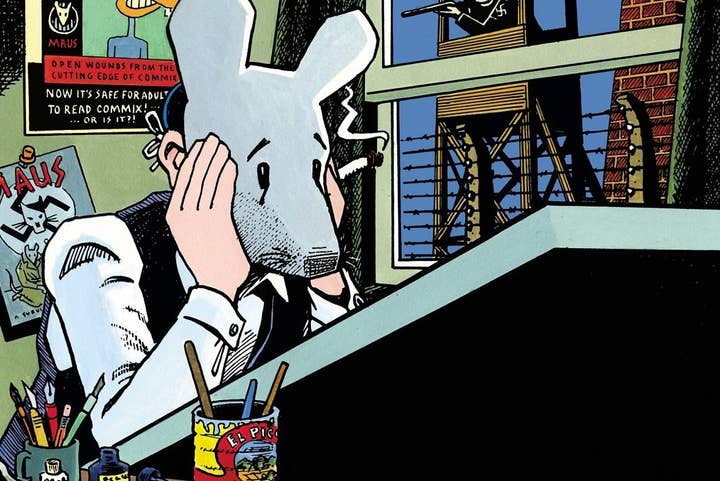

For the last couple of years, a career retrospective exhibit of Art Spiegelman's work has traveled the world, appearing in museums from Paris to New York, Cologne to Vancouver. Though Spiegelman's best-known creation is the Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus: A Survivor's Tale, the first display visitors see is not a heart-wrenching panel from the Holocaust comic, but a wall of Garbage Pail Kids cards.

Though his work would eventually make great strides in legitimizing comics as an art form to many cultural critics, Spiegelman began his career working for the Topps trading card company. While there, Spiegelman produced a juvenile brand of subversive entertainment whose aspirations, like those of many of today's popular games, seemed to top out at being mildly offensive and mildly clever (as with Alice Island, a Statue of Liberty-like Garbage Pail Kid covered in stinking refuse and holding high a ruptured trash bag).

It's a testament to the potential talent behind even the most readily dismissed or fleeting of cultural artifacts, and one that could easily serve as inspiration for game developers working on commercial products but aspiring to do more with the medium, to replicate the impact Maus had on comics. However, Spiegelman himself might caution against that goal.

"It's important that comics be positioned to get the grants, because they can't support themselves as comics. Comics have to be in museums, libraries, book stores, and studied in universities."

With the exhibit opening in Toronto at the Art Gallery of Ontario this week, Spiegelman was in town for an interview with AGO director and CEO Matthew Teitelbaum before the assembled press. During the discussion, Spiegelman recalled talking with Zippy the Pinhead creator Bill Griffith in the 1970s, as comics faded from mass market popularity. The topic was whether comics needed to make a "Faustian bargain with culture" in order to preserve themselves.

"It's important that comics be positioned to get the grants, because they can't support themselves as comics," Spiegelman said. "Comics have to be in museums, libraries, book stores, and studied in universities. It was literally a conversation as specific as that, and it seemed insane.

"The 'be careful what you wish for' part is that part of the energy of comics is that they didn't come with the daunting mantle of culture like opera, painting and the other grand arts. People just liked them and they paid attention to them. And they flew below the cultural radar at a level of intensity and a kind of culture that was very close to pornography."

"[P]art of the energy of comics is that they didn't come with the daunting mantle of culture like opera, painting and the other grand arts. People just liked them and they paid attention to them."

The danger of cultural adulation, Spiegelman continued, is that the medium becomes "so rarefied that it dries out," that it loses the energy and drive that made it distinct in the first place.

Though Spiegelman didn't address games directly, the parallels between games and comics--from their origins as commercial entertainment to their incredible popularity and subsequent demonization from concerned parents and politicians--are clear to see. But where comics took a century to make their path from the funny pages to museum halls, games have been dealing in a compressed timeline. They are disposable distractions for kids and Museum of Modern Art mainstays simultaneously. Big-budget blockbusters and free-to-play titans bring in billions even as an independent scene has thrived, giving rise to a period of experimental, personal, and transgressive game development that recalls the underground comics scene in which Spiegelman found his own voice.

Games and comics may visit the same places on their evolution, but they aren't doing it at the same pace, or in the same order. So while we may be tempted to celebrate the still-nascent cultural acceptance of games as a medium worthy of scrutiny, all players in the industry would be well-advised to consider the implications that has for the future.

Art Spiegelman's CO-MIX: A Retrospective opens this weekend at the AGO and runs through March 14.