Whitethorn Games and the art of cultivating slow gaming

Matthew White and Britt Dye discuss the indie push for accessibility, the wholesome games revolution, and "pastoral millennial gay escapism"

Ever since the release of Stardew Valley in 2016, a wave of life simulators and other self-professed wholesome games has washed over the games industry.

The most insecure fringe of the games community has seen this as a threat to what they consider the only valid way to enjoy games. But some of us are living our best life under a cosy blanket with a cup of tea, finally spoilt for choice in our genre of predilection.

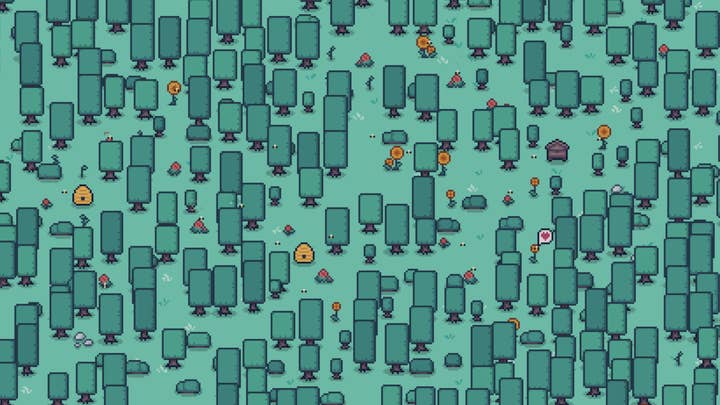

Whitethorn Games is part of the latter group. The Pennsylvania-based publisher launched in 2017 and is behind indie hits such as Calico, Wytchwood, Lake, and the recently-released beekeeping sim Apico.

The company focuses on catering to an audience that had been largely ignored until recently.

"We aim at a more casual audience – the word 'casual' has all this baggage within games that I try to stay away from, so they're not 'casual games', but they're games to be played casually if that makes sense," explains CEO and founder Matthew White. "We primarily focus on approachability and ease of access. Our audience is either young kids, or people who are a little older and have kids themselves. [For] our customers, games aren't their primary hobby.

"As a result we found really quick and happy friends in not-traditionally [represented] creators, so women, people of colour, queer folks, who have stories to tell that aren't necessarily 'run down that hallway and shoot people.' Our entire catalogue pretty much consists of these sort of slow, approachable experiences."

White says with a smile that he remembers using the term "pastoral millennial gay escapism" in the past to describe Whitethorn's catalogue. And he welcomes the myriad of titles now existing in this category with open arms.

He acknowledges that there is a trend-chasing factor to take into account, but says that the wholesome games boom is revolutionary because of the audience, not because of the titles it includes.

"The thing that binds the wholesome games together isn't really the games and the genres, it's that the audience is palpably different. Tower defence type things were super popular around the turn of the 2010s, then MOBAs had a moment in the League of Legends heyday, so there's always trends in games. But all of these things are for the same audience. It's shooters, MOBAs, white straight dudes, straight white dudes. And then you get a game where it's a photographic journey about taking a walk with my grandmother, and it's like maybe someone who isn't a white straight dude can finally be the audience for a title!

"Maybe with an infinite magic box that can create everything, the most interesting thing in the world is not a god damn M16"Matthew White

"I think the fact that this is a trend that's led by – and is for – people who are not the way the games industry has historically looked is more important than any conversation about wholesome vs non-wholesome.

"If you think about movements in the art world, the idea has always been that some non-traditional group has brought in this big groundswell of stuff that everyone is interested in, like pop art, and it's revolutionised art on an upward way. I think what you'll see here is a movement, slow but steady, of larger AAA things that are now considering that people are a little tired of just blowing out brains. Maybe with an infinite magic box that can create everything, the most interesting thing in the world is not a god damn M16. That is really the power of that movement."

For Whitethorn, favouring approachability in the titles it signs also means making sure these games are accessible. The publisher has a set of baseline accessibility standards that it encourages its studios to achieve before releasing, and it hired usability and accessibility specialist Britt Dye in 2021 to help with that goal.

"If something's not accessible, it's not usable by a lot of people," Dye says. "I have a background in information accessibility and helping people get to the information that they need through all kinds of barriers. I brought that with me when I started as a usability analyst here, and then I think that the two just go hand-in-hand because I can make sure that the barriers for a general audience are gone as well as for people with disabilities."

When working on titles targeting an audience that hasn't really played games before, approachability is key, White adds, and a big part of approachability is accessibility.

"You can't immediately approach a rock climbing wall if you are physically disabled," he says. "So what are the obstacles we remove before we even get to usability? Accessibility is door number one. If you can't even get in, you can't do anything, and then usability is the next logical step. Those two are not the same job but they are very related.

"I think a lot of people don't realise that the work that accessibility folks do directly ties into the usability of games for a general audience. These are pieces of the same puzzle."

When Whitethorn signs a new game, the first step is for Dye to go through the title and find any of the barriers she can find even before doing any testing, she explains.

"Then I talk to the developers and we work out a plan that logistically they're able to do based on how many people are on the team and other constraints. We are lucky to have developers who are interested in accessibility. A lot of times they're already working on [options]. For example, Princess Farmer was already working on a single handed mode for their game before I even came on board. Some stuff comes out after the fact, through feedback [from players]."

Dye's baseline options include a toggle for haptics, sans serif fonts, high contrast options, and button mapping, among others. The more in-depth features are decided on a case-by-case basis with the developers.

White says that they try their best to "implement the things that are the most logistically simple," to avoid putting a strain on the small indie teams they work with, as well as features that will benefit the greatest number of people.

"We do try to prioritise because unfortunately the business reality is that even though we want every accessibility option in every game, that's not something we currently are in a place where that makes sense financially," he explains.

"Much of the accessibility work we do is a bit like 'feminism benefits men even if they don't notice.' Much of the work we do tends to an audience that have physical disabilities, intellectual disabilities, visual or sensory disabilities. But they have the spillover benefit of helping individuals with something more run of the mill, more common, like colour blindness, that [affects] lots of us.

"A big part of it for us is feedback. We want to know the issues, especially from an accessibility and usability perspective. We know [disabilities] generally speaking, but the uniqueness and the [spectrum] of them is different with every person's body and every person's mind. We work with the Barber National Institute here, which is a national autism research institute, and Sight Centre, which is a low vision institute. But we're looking for more organisations so that we can find representative individuals that have a wide variety of physical, emotional, sensory and cognitive ability levels, [to] make these games more helpful."

He highlights that the financial value of usability and accessibility can be difficult to grasp, and the cold reality of running a business can be a challenge.

"With something like usability, we don't really see the value in a financial way until we see the critical reception of the game and everybody's really happy about it. But it's a high risk to implement. One of the reasons you don't see that happening across the board right now is because there isn't a strong push from the top. The big folks [have] yet to push these features in."

He points out that despite financial constraints, the driving force behind furthering accessibility is mostly indie developers. Microsoft has of course been at the forefront of these efforts, and Sony is slowly but surely catching up, but indies are the "tip of the spear," he says.

"If you go look at the accessibility tags that Microsoft maintains on its store, those who have the accessibility tags tend to all be indies. We're looking for those unique ways to be conversant, we are sometimes the trickle up force [who] tell the big boys to catch up.

"Microsoft certainly invested heavily into accessibility and access to games for everybody and I think that's great, and we get those resources directly from them. You need the big fish to commit as well. [We can] do the work but ultimately, we're not drawing on a trillion dollar budget line like Microsoft or similar."

"Just listen to guidelines, listen to the players, join any online communities you can with disabled players, and listen to them"Britt Dye

He continues: "Until we have great big AAAs leading by example, it's difficult for us to even find the funds to do most of these things. We certainly try, but a lot of the time we're simply limited by the fact that we published 30 games. It becomes resource constraining sometimes in a way that I'm not really thrilled with. That's the challenge."

White also talks about the worry some indies might have about doing things perfectly when implementing usability or accessibility options.

"I think there's trepidation among indies to throw something in and be seen as just trying to tag it on for marketing purposes. But what I will say is: do it anyway. I think the people out there who are legitimately disabled, you might not hear them on Twitter, but they're there and they will benefit. So just do it anyway. Even if you do it and it's not perfect, go grab the Unity dyslexic font from the asset store and you slap in an option for that... even if you didn't do it perfectly, you helped somebody. Just diving in and doing it is important."

Dye concludes: "The main thing would be to try to learn from those things, and just listen to guidelines, listen to the players, join any online communities you can with disabled players, and listen to them."