The UK games industry is at a regulatory crossroads | Opinion

Harbottle & Lewis' Kostya Lobov breaks down the potential impact of various government initiatives and investigations

The wheels of the regulatory machine may turn relatively slowly, but they do keep turning. A few weeks ago, the Digital, Culture, Media & Sports Select Committee published the results of its investigation into immersive and addictive technologies -- a large part of which are directed at games.

The 84-page report is the result of a nine-month evidence gathering exercise and makes for an eye-opening read for the games industry. It's worth a reminder that this is not yet new law and, in some cases, the ball has been put back into the Government's court to provide a response -- a Government that has other priorities on its mind at the moment, and which could potentially look very different in a matter of months. However, if implemented, the report could have a major impact on studios and publishers and require them to make changes to their business models and games.

What follows is a highlights reel, illustrating the key potential impacts.

Loot boxes

The Committee believes that loot boxes which are paid for with real money are a form of gambling, and that the Government should amend the Gambling Act to reflect this. The specifics are not clear, but the suggestion seems to be that this should be the case whether or not the value of the prizes from the loot box can be 'cashed out.'

"For some games, making loot box-type mechanics unavailable on a per-user basis may simply not be possible"

If the Government does not follow the Committee's recommendation, it has been asked to produce a paper explaining its reasoning. If the Government does follow the recommendation, it would mean that studios and publishers who want to use such loot boxes in their games would need to obtain a Gambling Licence from the UK Gambling Commission, which in practice would be unworkable in many cases.

This is a drastic departure from what the UK Gambling Commission indicated last year and, if implemented, it could bring the UK more closely in line with other European countries which have adopted a tough stance on loot boxes.

The Committee has also recommended that loot boxes which contain an element of chance should not be sold to children, until further research can be carried out into the potential harm they cause. The proposed blanket ban is described as "precautionary," until evidence shows that no harm is done to children by exposing them to these mechanics (but in the knowledge that such evidence may not materialise).

The report is not clear on whether the proposed ban would apply to games played by children as a whole, or whether loot boxes may be permitted to exist within a game as long as any children who play it are not exposed to them. For some games, making loot box-type mechanics unavailable on a per-user basis may simply not be possible, so in practice the proposal could amount to a blanket ban on loot boxes, assuming the game is played by children.

For some studios, loot boxes were already a poisoned pill to be avoided at all costs. For others, if the recommendations in this report are implemented, it could be the final nail in the coffin.

One of the reasons behind the proposed widening of the definition of 'money's worth' is to capture subjective (as opposed to just objective and monetary) value to a player. But the consequences of doing so would need to be considered carefully, as it could inadvertently catch a lot of other activities that involve spending money, chance, and a prize which is subjectively of value to the player.

Online Harms

The Committee has expressly stated that it believes any gambling-related harms associated with gaming should be recognised under the Online Harms framework. This is a reference to the Government's Online Harms white paper, published earlier this year, which recommended (among others things) the establishment of a new statutory duty of care to make companies take more responsibility for the safety of their users, and tackle harm caused by content or activity on their services, to be overseen and enforced by an independent regulator.

On this subject, the Committee has recommended the establishment of a scientific working group focusing on the effects of gambling-like mechanics in games. The results of this research are intended to inform the Government's forthcoming Online Harms legislation, which could be implemented as early as 2020.

Industry funded research into psycho-social harms

"The report is highly critical of what the Committee perceived as a lack of transparency on the games industry's part"

The Committee has recommended for high-quality, independent research into the long-term effects of playing video games. It has called for games companies to share aggregated player data with researchers and to contribute financially to the research through a levy. The call for further research, and its funding in this way, is in line with the Committee's overall sentiment that games companies need to be more proactive in investigating and addressing the issues raised.

However, a number of questions remain unanswered, such as which game companies will be required to take part in the research and to contribute to the levy, and what that levy will be. Although this is not yet known, it is logical to assume that the focus would be primarily on larger studios and publishers.

There will inevitably be sensitivity around the sharing of data with third party researchers, which could be commercially damaging if inadvertently leaked.

Age ratings

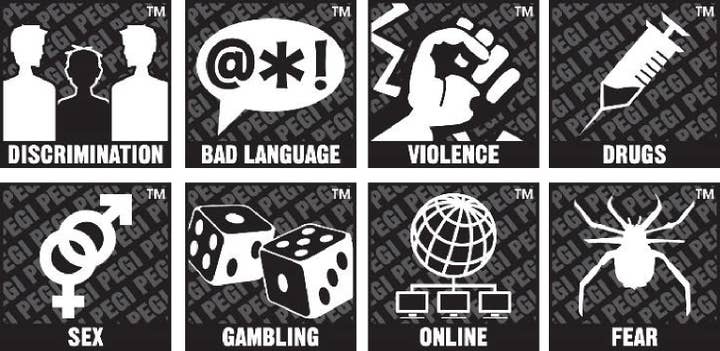

Currently, under the Video Recordings Act 1984, PEGI 12, 16 and 18 rated games cannot legally be sold as boxed products to anyone under those ages. The Act does not explicitly deal with digitally distributed and online games. The Committee's recommendation would see the scope of the Act widened to encompass digitally distributed and online games, making it a statutory obligation enforceable under English law. This would essentially mean that online games are covered by the same enforceable age restrictions as physical copies.

In practice, PEGI ratings are already often used by publishers and platforms for online games on a voluntary basis, and this approach seems to have worked well for a number of years. The Committee's recommendation for a stricter approach, while seemingly unnecessary, is consistent with the general tone of the report.

Player engagement, game design mechanics, and age restrictions

A substantial section of the report focuses on game design and the use of data to increase player engagement (e.g. through dynamic difficulty adjustments, direct offers).

A particular frustration of the Committee is the unavailability of data for 'average levels of engagement,' to help it to determine what may or may not be considered a 'healthy' amount of game play. It noted that: "Games companies collect this information for their own marketing and design purposes; however, in evidence to us, representatives from the games industry were wilfully obtuse in answering our questions about typical patterns of play."

This is an over-simplification which, in the case of some games, does not do justice to their complexity and the difficulty of determining what is an 'average' level of engagement, but it highlights an area in which the industry will have to work to educate regulators and re-establish trust.

In a rare section of the report which is not directed exclusively at the games industry (but also to social media), the Committee expressed serious concern that there is no effective system in place to keep children off age-restricted platforms and games, and criticised companies for being reactive in addressing this problem.

"The industry is at a regulatory crossroads, but it is not too late to influence how the legislative agenda of the next few years will unfold"

The Committee's concerns about game design mechanics are directed at the use of techniques designed to keep players playing. It acknowledges that studios understandably want players to like their games, which is not inherently objectionable, but concludes that there is enough evidence that some players have lost the ability to control their amount of engagement and spending to justify "a greater sense of duty of care in the way products are designed."

The list of mechanics potentially in the firing line is very broad, including high event frequencies, deliberate near misses, variable ratio reinforcement schedules, the use of "light, colour, and sound effects" and more general features such as persistent worlds found in MMORPGs. The Committee's view is that the games industry's emphasis on player choice does not acknowledge the way in which many games use random reward mechanisms that have allegedly been proven to create repetitive behaviours, and the effect that this might have on the meaningful exercise of choice.

As with loot boxes, the report is highly critical of what the Committee perceived as a lack of transparency on the games industry's part. It has called on the Government to set out how it intends to support independent research into this; such research to inform the development of a behavioural design code of practice (to tie in with the Government's plans for a new Online Harms regulator, as mentioned above).

Esports and player wellbeing

The report identifies esports as an area of growth and innovation but notes that there are no common standards for the duty of care that esports teams have to their players, as exist for other sports such as football.

As well as suggesting that esports could go further in the promotion of player wellbeing and promotion of healthy gaming in schools, the Committee states that there are "significant opportunities for the development of esports in the UK to harness best practice in the use and monetisation of player data, which could serve as a model for other parts of the games industry." The meaning of this is unclear, but the broad message appears to be that, when it comes to player data and monetisation, similar 'best practices' should apply to both the games and esports industries.

Next steps

The Committee's report has put the onus on the Government to respond to number of the points raised. With all the uncertainties regarding Brexit, it has hard to predict how quickly the Government will respond, albeit some are expecting a response before the end of the year.

In any event, the significance of the Committee's findings should not be underestimated. Part of the Committee's intention is to elicit a reaction from industry, and the UK games industry's response to the findings will be a crucial (and possibly final) opportunity to influence what and how future laws are implemented.

The industry is at a regulatory crossroads, but it is not too late to influence how the legislative agenda of the next few years will unfold. At the same time, studios and publishers should be mindful of the increased mainstream press interest and potentially adverse PR which the Committee's report could bring (particularly as it has already been widely covered by the press), and will need to be ready to deal with requests for comment from the media and other third parties.

Alan Moss and Kostya Lobov are lawyers who advise on all things games and e-sports related at London-based law firm Harbottle & Lewis.