Investigating Her Story

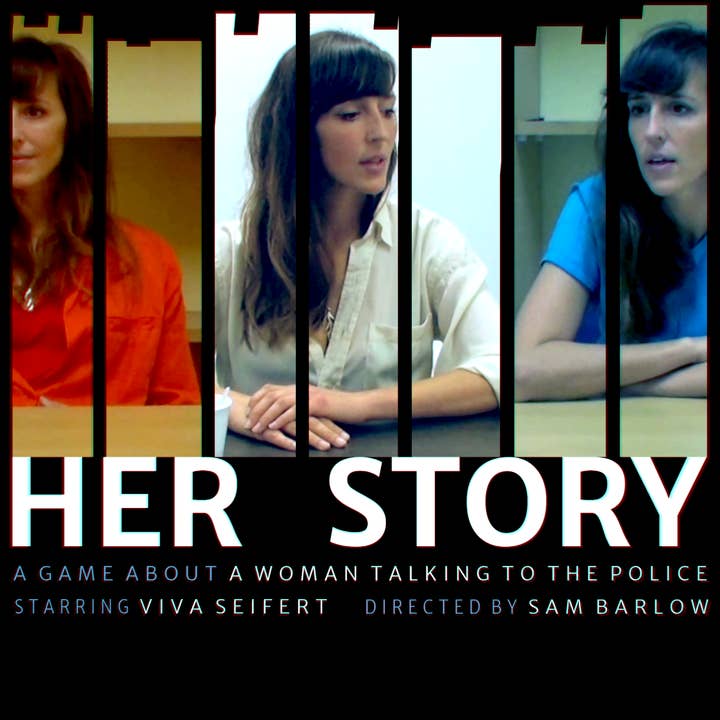

Jurie Horneman talks to Sam Barlow about one of the year's brightest indie gems

Like many people, I have recently been playing Her Story, Sam Barlow's full motion video police procedural game. I was impressed by its accessibility, its unique approach, and the high-value experience it offers despite its presumably modest budget. Many aspects reminded me of the things I talked about in my article on innovation. Mr. Barlow does some things nobody else does, or hasn't been doing in a long time, and succeeds brilliantly. I was curious what the story behind it was, so I sent him a few questions, and received some fascinating thoughts on interactive storytelling in return.

Q: Her Story is immediately remarkable because nobody makes FMV games anymore, and I don't expect that many developers to be capable of directing actors. It seems you've found a game concept that is both unique and hard to replicate. Additionally, the game is easy to understand and to play for inexperienced gamers, it has an intriguing storyline, and probably wasn't incredibly expensive to make. Deciding which game to make is a difficult design problem in itself, and it seems you've found a very fertile sweet spot. How much thought went into that? Did you consciously try to come up with a concept with good bang for the buck, or did it just hit you in the shower one day?

Sam Barlow: There were two parts to me deciding to make this particular game. The first was the realisation that I could go indie and still make something worthwhile - this became apparent when I noticed my intense professional jealousy (and admiration!) towards certain indie developers, developers who were making brilliantly executed games that had original and personal ideas at their heart. Working within the traditional console system you can become quite blinkered, you start to think that you can only achieve something with a team of a hundred people and tens of millions of pounds. So seeing those examples - games like Year Walk, Blackbar, 80 Days, etc. - gave me the confidence that embracing the freedom of indie dev wouldn't mean giving up the ability to make something worthwhile for a large audience.

"I noticed my intense professional jealousy (and admiration!) towards certain indie developers, developers who were making brilliantly executed games that had original and personal ideas at their heart"

Then the hard part, having made this decision: I needed an idea. It had to be achievable, it had to be original and it had to be something that - like the examples I have given - could be executed to its fullest level. I didn't want to make a compromised game, one that would always be better if it had a larger budget. It had to be an idea I was in love with, and I had to be realistic - could I bring the idea to fruition and would there be enough magic there for it to capture people's imaginations? I had lots of ideas, but they didn't tick all the boxes. So I kept - to paraphrase David Lynch - fishing, casting out in hope of hooking a Big Fish. Whilst the idea for Her Story was something I was shooting for - a way to make something in the police procedural genre - and whilst the inspirations for it are things I can in retrospect trace back and figure out, its arrival on the scene was entirely down to my subconscious.

John Cleese talks about creativity being about putting together two ideas that no-one else has put together before. These idea collisions don't usually sneak up on you, they just jump out and smack you in the face. And it was that kind of a deal - my brain threw together the interview room, the idea of video content and the mechanic of the database interface. It popped into my brain fairly fully formed. At that point, I fell in love instantly - here was an idea that had a unique aesthetic, it had a unique gameplay hook and could be done in such a way as to invite a broad audience. One of the things I hadn't wanted to leave behind by stepping outside of AAA development was working with performers and here was an idea where I could actually put the performance at the centre! Perfect! I didn't waste a second from that point.

Q: I noticed similarities between Her Story and Aisle in that, from an outside point of view, both have content that can be accessed randomly, and the game does not contain state, so the player does not really affect what happens. I may of course well be wrong about both games. Are the Aisle-like qualities of Her Story intentional, accidental, or all in my head?

Sam Barlow: I definitely have a love for games where state and logic occur outside the game itself. I think there's something profoundly affecting about this. The game isn't pandering to the player in the way that some hyperactive blockbuster games do - every ten seconds giving feedback, telling them they are doing the right thing; the whole world engineered for the benefit of the player, its life growing dimmer as the player moves away from it. I have a deep love for games where the world has limited interaction and where the space does not have that theme park feel of having been artfully designed to lead the player around and create 'flow'. So I like old games such as Goldeneye and Soul Reaver, where the awkward development processes created spaces that were empty or full of dead ends and curiosities never resolved by the game, or low fidelity, mysterious places like Zelda: Ocarina of Time's field. These spaces feel more authentic and interesting because they don't appear to be designed for your entertainment (Dan Pinchbeck did a lovely post on this subject recently!)

"I also feel that a part of video games that is becoming less and less prevalent is the direct engagement of the player's imagination...I think this is key for storytelling"

I also feel that a part of video games that is becoming less and less prevalent is the direct engagement of the player's imagination. And I think this is key for storytelling. So in a medium like cinema where the core of that medium is pointing a camera at things and recording the imagery, you find that the craft and the art often lies with what you don't show - in the cut, in montage and in having the player imagine what is off screen, off the gaze of its protagonists and what takes place in-between scenes. The modern video game is so in love with contiguous, continuous time and space - 'immersive' exploration of 3D spaces - that we eliminate all these possibilities. There are games which address this - 30 Flights of Loving's interpretation of cinematic cuts; Everybody's Gone to the Rapture's use of abstract representations of characters to allow you to imagine them.

What is nice about Aisle and Her Story is that the game cultivates this space for players to imagine and also forces them to constantly refine their idea of what is happening through a back and forth dialogue. This interactivity allows you to directly engage with the imagined spaces, 'casting out' and fishing for details to grab onto. So there's a tactile sense to your involvement. And despite the fact that the content is 'static' - pre-written, in no way reactive to your interaction - it does feel as if you're conjuring it up through your free-associated inputs, it feels like you are somehow involved in the creation of the content - like an explorer who stakes a claim over a species he discovers. Partly this is because your words summon it out of the void - and this is a very unique aspect of video games: we can hide content from players - behind the small screen of an iPad we can conceal a warehouse full of stuff... and the player is none the wiser. This sleight of hand is a very powerful part of the video game juju for me.

Coming back to your question more directly: before I started to develop Her Story I was finding out that there were a lot of people out there who had fond memories of Aisle and were still sharing it out to friends. I saw a couple of live performances of it that brought home its particular blend of accessibility and the excitement its open ended invitation created in players. It seemed like there was as much awareness and/or love for that game as for the more recent Silent Hill: Shattered Memories. That gave me confidence that there was still an appetite for experiences with that kind of feel and definitely helped me take the leap of making something quite so non-linear and free for the player.

Q: How hard was it for you to shape the player's experience given that the game is very non-linear? Did you use any tools, processes, or run-time code to help manage the experience for the player? Did you use interactive fiction for prototyping? Or were you just able to keep it all in your head?

Sam Barlow: I think this comes down to two parts of the process. First, there was upfront research and writing. So I went deep on the process of police interviews. I read up on the psychology, the use of language and the way these rituals plug into deep storytelling structures. I created very detailed documents charting the characters and the events that the game explores. I spent a lot of time on this - probably half the development time. Ensuring the events, characters, imagery, etc. had a richness to them so that the material sparked off itself. Once this was done, the characters were alive in my head and it was easy to then sit down and allow them to talk and work through the interviews. The seven dialogues essentially wrote themselves at this point - my job was to sit back and let the characters interact and write it all down. Early on I had done some experiments using real world interview transcripts and was surprised to find how enjoyable it was to 'play' them with Her Story's mechanics. It really solidified for me the idea that the dialogues should be 'realistically' short and naturalistic. So my aim here was to create seven interviews which had the sense of real conversations, had a back and forth flow to them.

"Once I had the first draft of the dialogues down I then fed them into a big spreadsheet. I broke them down into all their unique words and analysed their use. This identified words that occurred too little, or too much"

Once I had the first draft of the dialogues down I then fed them into a big spreadsheet. I broke them down into all their unique words and analysed their use. This identified words that occurred too little, or too much. I would then drill down into the 'slices' created by searching for these words and sculpt them by changing words to tweak what clips were returned. So this was a combination of simple maths - ensuring the interconnectivity and distribution of the clips and their words was strong; and the process of sculpture - looking from different perspectives and chipping away to create a pleasing three-dimensional thing.

These kinds of approaches have always appealed to me. They allow me to write like a writer and then make use of brute force maths to pull everything into shape. It's the same process that worked for both Aisle and Shattered Memories. The way the 'psychological profile' worked in Silent Hill was such that I could approach variation in a scene as a writer, choosing interesting angles to write and then assigning them a profile - rather than working to a large, cold branching flow diagram. I think divorcing choice and consequence from a direct and immediate causation is actually quite important when writing interactive stories: having a richer set of numbers, a more analogue thing to tie your writing to prevents you from reducing your characters to clockwork.

Q: Story is perhaps my favorite force multiplier in game development: a reasonably small amount of effort can have a huge effect on the player experience. What do you think about the state of storytelling in games today? Do you see it as something that small developers can make use of to differentiate their games from others'?

Sam Barlow: I think the expectation of storytelling has come in leaps and bounds. And you see this at all ends of the spectrum. So even the dumbest shoot 'em up now has swathes of world building and characters, not to mention the money spent of big name writers and performers. So it's clearly a big deal, whatever the game you're making. My frustrations are mostly aimed at the very simple idea people have of the way the player is supposed to enjoy these stories.

"The idea of the player as the protagonist, the idea of moving towards the 'holodeck' ideal is a huge red herring to me"

The idea of the player as the protagonist, the idea of moving towards the 'holodeck' ideal is a huge red herring to me. I think all art works with a frame - all art requires the combination of intense emotional involvement, empathy and a level of remove that allows you to process the ideas and themes as things happen. The holodeck doesn't make sense to me as a storytelling idea because it removes the frame, it stops being a story and becomes a theme park. It would also mean a lot of stories with a terrible actor playing their lead...

AAA is pretty committed to this fantasy - especially at the marketing level - so I don't think they are going to turn the ship around any time soon. And so it falls to the smaller developers to capitalise on this blindness. If we can think harder and deeper about the real relationship between a player and the protagonists of a game, we can create experiences that engage players more deeply and move them far more than the bigger budget titles. This is clearly a matter of thinking harder and working harder (look at the brute force efforts of Inkle!) Lacking money, these are resources that a smaller developer is forced to rely on!