Funcom: "We were back in full production the day after they came"

How the Oslo studio survived the F2P transition, job losses and a visit from police

Funcom doesn't seem like a company that's recently been visited by the police. It might just be the influence of the LEGO littered around the office - a legacy of the Minifigs game currently in development there, but the staff seem cheerful and engaged: greeting the brass with enthusiasm as I'm taken on a tour of a new, smaller studio. Obviously, they knew I was coming, so there might be a touch of the 'say cheese' about the 45 or so faces I'm introduced to, but this definitely doesn't seem like a place that is overly concerned about an ongoing investigation from the rather ominous sounding 'Økokrim' - Norway's National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime.

Two weeks ago, the Økokrim arrived at the office, seized a number of computers, inquired after some documentation and took their leave. Staff were sent home for the day and trading in the company stock was briefly halted. News articles of varying accuracy started to seed, ranging from the cautious to the over-zealous. The rumour mill was in full flow, so, perhaps a little belatedly, Funcom issued a statement. Everything is fine. We're co-operating. Staff were sent home for convenience and nobody has been personally charged with anything. Don't worry about it. A robust PR message, but when you've just downsized massively, people will talk.

"There was speculation that we were out of business and that the Økokrim had taken all of our computers," says CEO Ole Schreiner. "They took a handful of computers, didn't touch the production environment and gave them back two days later. We were back in full production the day after they came. So even though it was quite a dramatic event, it all blew over very fast. The police were very professional."

"They took a handful of computers, didn't touch the production environment and gave them back two days later. We were back in full production the day after they came"

Ole Schreiner, CEO

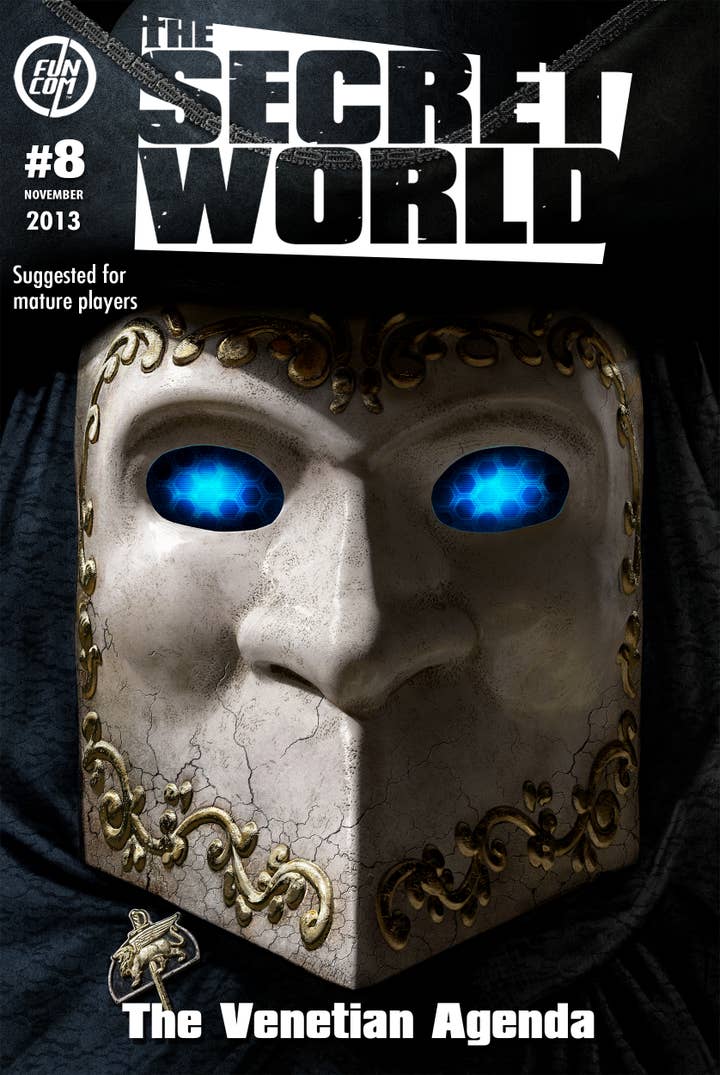

Schreiner is fairly new to the job. He was promoted from COO in July 2012 after the previous CEO, Trond Arne Aas, moved to become a "strategic advisor to the board and chief strategy officer". This was the day before the company launched its new and much anticipated MMO: The Secret World. A story of shadowy cabals and monstrous plots, The Secret World's new twist on the western fantasy MMO had attracted positive press, leaving Funcom expecting a winner. When the game launched, they were in for a shock.

Instead of the "Conan-like scenario" which the team had presented to investors and the market, the game sold just 200,000 copies in its first two months - despite over 1.5 million players registering for the game's beta. Low scores in the press and the proximity and popularity of the Diablo III and Guild Wars 2 launches were cited as the causes of the sales, but that didn't stop stock prices plummeting or a brutal round of layoffs which saw the loss of half of the company's staff. A big risk hadn't paid off, but more bad news was on the way.

On September 11, 2012, The Escapist reported that an anonymous insider had been in touch to make some serious accusations. The timing of Aas' departure hadn't been coincidence, they claimed. Nor was it a matter of stepping down as a major project shipped. They were alleging that his change in job was to ensure that he was removed from the list of the company's "primary insiders", enabling him to dump 650,000 shares the day before launch without undergoing the scrutiny of the financial regulator. He was, it was claimed, entirely aware of the imminent shortcomings of TSW and had ducked out to cash in whilst he still could: insider trading. That, combined with the considerably rosier picture which Funcom had presented to press and investors in forward-looking financial statements, also lead to a wider charge of intentional market manipulation.

It was these charges that the Økokrim were following up. Financial investigation takes a long time, and documents and paper trails can be incredibly convoluted, so it's likely that this was a matter of tying up loose ends, but as Schreiner continues to explain, it's been an exasperating process.

"It's the same case," he tells me, with the look of a man who's been put through the bureaucratic mill. "What we know is actually very little and the few things we do know, we can't talk about, because it's an ongoing case. The investigation began in 2012 and it's assumed that this is that investigation being prolonged, that has lead to this charge against Funcom N.V.: the company which is listed on the Oslo stock exchange, the holding company. The charges are two-fold. The first is that Funcom, between August 2011 and August 2012, manipulated the market. The other is that we had wrongfully filed insider information.

"No current employees of Funcom have been charged. We don't really know any more than that, so a handful of us, me included, have been interviewed as witnesses. We've been cooperating fully with the police on everything, giving all our information and helping when they need any more documents. We definitely want this case out in the open and done with as soon as possible."

"The second charge is fairly common," adds Morten Larssen, Funcom's voluble SVP of sales and marketing. "Norway's biggest bank, which is partly state-owned was charged with it last year, it happens quite a lot. So it's the first charge we feel we really want to shed light on. Coming from the entertainment industry, everyone knows how hard it is to predict how well an entertainment release will perform before it's launched. Look at the Lone Ranger. Gore Verbinski, Johnny Depp - same writing team as the Pirates of the Caribbean, which all opened at $100 million plus. They choose a perfect launch weekend over the fourth of July, and it bombed. $29 million and it's gone. It's very hard to predict - so many little pieces and so much opinion."

"We've been cooperating fully with the police on everything, giving all our information and helping when they need any more documents. We definitely want this case out in the open and done with as soon as possible"

"We had to take a lot of phone calls and do a lot of documentation," Schreiner sighs, when I ask him what the impact of the charges was on investors and shareholders. "But we're in a very positive situation where our biggest creditor is also our biggest owner. He's been with us since 1997. He owns something like 21 per cent of the shares. He has more shares than anyone else, the next biggest is about 1.52 per cent. So in general we had to update the market, as we had so many free-floating shares, and keep a good relationship with our biggest creditor. He also has two employees on the board, so they're constantly updated. So that was all taken care of pretty quickly. The more intense work was afterwards, with the people who assumed more had happened than actually had.

"But I think things have settled. We have to take some criticism about not keeping the press well enough informed. The only thing that the police have told us is that the company might get fined, that's what we know. We've had no indication whatsoever of the potential magnitude of that fine or how long it could take. We want to cooperate as much as possible and get things done."

The case rumbles on, which means that I've got all the information I'm going to get about it from Larssen and Schreiner. There's a fairly sensible line between clearing the air and risking contempt of court, so the conversation shifts towards a more forward-looking issue: what Funcom needs to do to survive.

"Our strategy is now make more focused online games with budgets of around $3-5 million initial investment," Schreiner explains as he outlines the studio's future. "Games based on brands with a one year production time - we hope to launch a game or two a year, in the future. If we can execute on that strategy, we'll be in a very good position in a couple of years.

"When I took over in 2012, the change in strategy was already in the works. It was clear that it was unlikely that Funcom would build a $40-50 million MMO again - we were shifting to smaller investments, more focused games that were cross-platform.

"We needed to do that because the market trends were going in that direction, so it was natural, but of course the low sales of The Secret World meant that we had to be pretty drastic. I was told I was crazy for thinking the company would survive if I cut 75 per cent of the staff, but we had to. It's remarkable that we did survive, but now I think that we're much better aligned to meet the current market and much more able to adapt to market changes more quickly.

"By doing this we're reducing risk dramatically and increasing the likelihood of having a success by doing one or two games a year. We're also much more likely to be able to survive failures. We can take risks, go in more fancy directions, try new stuff and not be dependent on a single success for survival. We need a stable economy in place before we take too many risks.

"When I took over I wanted to make a company that made smaller bets, consisting of smaller, more agile teams that worked together as a group, making games that they deliver every 12 to 24 months. That was my aim. I believed The Secret World would bring in enough cash to execute that strategy."

"It's key that the $3-5 million figure is an initial investment," Larssen interjects. "The core change to the market has been digital distribution to all platforms. That means, as a developer of our size and experience, we can reach consumers directly with no stock-risk, no silver disc fee to Sony or Microsoft. Also, the market is used to games with a smaller initial investment which are built up later. Clash of Clans, I think, cost about $1.5 million, but they've invested way more afterwards - you can put a game out, see what works and add more, keep investing, instead of having that huge, upfront $50-$100 million and just crossing your fingers and hoping that it works. That model killed so many great studios."

"you can put a game out, see what works and add more, keep investing, instead of having that huge, upfront $50-$100 million and just crossing your fingers and hoping that it works"

Morten Larssen, SVP, Marketing and Sales

It surprises me to find that all of Funcom's games, from the 13-year old Anarchy Online to The Secret World, are all running at a steady profit. That's not to say they've all necessarily recouped their costs, but they're at least getting there. Smaller, more frequent projects can be run in the same way, trimming as necessary to keep them on a trajectory towards recovering the initial investment, arriving at break-even much more quickly. But MMOs and frequently-updated digital games cost a lot of money to run and maintain. Studios need to allow for customer services, admins, server costs, bandwidth and the production of new content.

For Funcom, the key to keeping those costs minimal is the company's proprietary technology: the Dreamworld engine. It has, as the name suggests, been the company's main, if not only, development tool since the days of Ragnar Tornquist's seminal Dreamfall adventures, which means that the staff who've been there just as long, know it inside out.

"It's pretty unique," says Schriener. "It's not so much about the technology as the knowledge, which we've been building for 13 years. It's a platform - it has all the elements you need to make, run and maintain a game - from the production tools right down to the customer service and QA tools.

"When we started the LEGO minifigure project in September 2012 with just four people, it took them six weeks to build a client which was up and running with a few minifigs running around, fighting. It was simple, but it had chat, server connection, billing, customer services, everything."

"You can cheat in other ways," Larssen allows. "You could have built it in Unity in that time, for example. But that would have to then be rebuilt to add server connections etc. With this, I could just send you the .exe and you can test it against the server, it's a modular platform."

Shreiner and Larssen have a good patter, a smooth baton-passing in conversation that comes from presenting similar materials many times over. Larssen often plays for laughs, with Schreiner taking the role of straight man - but it's easy to see that they're both in good spirits.

"Developers underestimate the tools you need to run and maintain a game," says Schreiner as he retakes the reins. "It takes a lot of time and effort to make them - to make them good takes years of trial and error."

The LEGO minifigures game that the studio is currently working on is an isometric, brick-busting affair which is aimed firmly at the child and parent audience. Up to four players can join instances together, running around and levelling up their iconic minifigures whilst unlocking new ones. Each minifigure is based on an actual LEGO model, from the ranges of shiny bags that you see at supermarket checkouts and toyshops all over the world. Each will have a set of unique powers with which to tackle the game's obstacles.

What's really special about it, though, is its cross platform nature. Funcom has managed to get the Dreamworld tech running across PC, Android, iOS and console.

"What we're making to make it run on iPads, Android and hopefully Xbox One and PlayStation 4 in the future, are render engines to make it actually play on your screen," Schreiner tells me. "Of course you have to tweak controls etc, but in general you can get a game running on those platform in six weeks. If we go totally cross platform, we can tune entirely to the way the market moves. Our goal is to minimise risk by having a technology that allows us to quickly adjust and adapt to the market trends. We want to be able to make money from new trends."

"We had a working 360 version of Conan running for quite some time," adds Larssen, pre-empting my next question. "We, along with some other MMO companies, were in discussions with Microsoft about how to do that - but it never happened for any of us. The set-up was too limited to be able to constantly update and add patches or new content. They had a very rigorous set-up that was very difficult for a live online game to successfully thrive under."

Coming back to Conan raises another point. That game sold very well, initially, but as subscribers dropped off it was clear that it wasn't going to be the runaway success it had initially promised. So why go for the hard eight and take another big risk on The Secret World?

"It was an assessment of where we were," answers Larssen. "The Secret World was started some time before we shipped Conan, although not with a full team at that point. Conan was the best-selling MMO of 2008, so it wasn't until late 2008, early 2009 when we'd realise that this wasn't just a medium downturn because Warhammer was launching or whatever. It was the model - and we saw it happening to a lot of other games. A lot of investment had already gone into TSW and we strongly believed in the premise. So in 2009 we had a lot of internal discussions about whether we should change the way the game was presented. Free-to-play wasn't an option in 2009. There were very few successful big games in that space. It was mentioned, but it wasn't a big thing we were seriously considering."

Schreiner chips in again.

"Membership by subscription was by far the most common option and was of course a business model that was proven, and proven again and again. Even though we'd started to see that curve changing.

"Even before I took over, Funcom was changing the way it worked. We did make a kids game with Pets Vs. Monsters, we did enter the social space and we have had prototyping teams flirting with new areas of the industry. So from a historical perspective this new strategy is a natural evolution of the company. We would have taken this path anyway, no matter how The Secret World turned out."

So with a smaller staff, a tighter focus and a globally-recognised IP behind their new title, Schreiner and Larssen may well expect a sudden turnaround of fortunes. The company's latest financials showed a big swing towards profit, stopping around $75K short - will next quarter bring that magical step into the black?

"this new strategy is a natural evolution of the company. We would have taken this path anyway, no matter how The Secret World turned out"

"No," says Schreiner, matter of factly. "We think that revenues will still decline until the launch of LEGO, that's our prediction. Now we've done all the restructuring, operating costs will be stable. Revenue in existing games will slowly decline over time, that's the long term trend. It will have bumps, but we don't expect anything major to happen. The strategy is to maximise the revenue we can get and minimise cost. That's the strategy we're using for our online portfolio and we hope to be as innovative as possible with our new projects."

Once more, Larssen is a little more positive, and I get the sense that he's a major motivational force for the staff, that he and Schreiner complement each other extremely well.

"Of course there are the outliers," he says, with a quick grin. "If you hit it off, they can be huge. The best comparison in the industry right now is Gung-Ho. They were a very similar company to Funcom - they were a strange bird in the Japanese space, a PC MMO developer. Then they had this little skunkworks project called Puzzles and Dragons. They never expected that to happen. They have no business plan, no revenue projection that expected a game which would keep bringing them $3.5 million dollars a day, it's crazy."

Optimism is alive and well in Oslo, and long may it continue.