Developers need a better advocate

The IGDA is supposed to be looking out for developers' interests, but it doesn't have the resources or the leverage to do it effectively

Last week at the Game Developers Conference, the executive director of the International Game Developers Association Jen MacLean conducted a series of interviews with the gaming press.

The group wanted to discuss a "relaunch" with new board members and member benefits, but as you might have seen, many of the interviews centered around the discussion of unions and MacLean's skepticism of having them in the games industry. That was certainly true of my interview, which you can read here.

But I'll be the first to say that the badgering MacLean faced over unions wasn't entirely fair; it's just that she is the closest thing we have to an appropriate person to ask about them.

When violent video games become headline news, we can go to trade groups like the Entertainment Software Association for comment, because they represent an assortment of the largest game publishers. They are explicitly responsible for advocating in their members' interests, and they can do so effectively. To put it bluntly, the IGDA claims it advocates on behalf of developers, but it does so rarely and, usually even then, ineffectively.

"The IGDA relies on volunteers, but effective advocacy requires full-time focus and sustained effort"

Advocacy is just one of four key areas of focus in the IGDA's mission statement. In addition to pushing for change on behalf of developers, the group wants to help its members network, further their professional development, and grow the industry internationally. On those last three counts, the IGDA has a history of succeeding by any reasonable measure through its local chapters, webinars, and events. However, on the advocacy front, the IGDA has proven itself to be either utterly ineffective or inexcusably indifferent to the interests of developers.

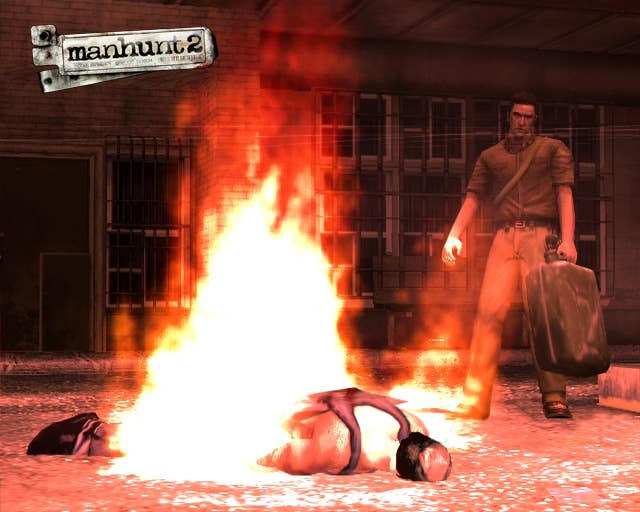

In 2007, developers at Rockstar Vienna discovered that they weren't acknowledged in the credits for Manhunt 2 because Rockstar had shuttered the studio after two years on the game and moved the project to its London location to finish up. In a rare burst of public advocacy for developers, the IGDA called for industry-wide adoption of standards for in-game credits, and formed a committee to propose them. The chair of the committee also planned to host a GDC roundtable session titled, "The IGDA Credits Movement: The Revolution Is Already Here."

The revolution was not televised, or streamed, or ever really fomented. The IGDA never formally proposed standards, and the industry still lacks them.

When we asked MacLean (who served on the IGDA board of directors during that time) about it, she attributed the failure as a challenge inherent to a volunteer organization. It's hard to get people's best efforts and keep them motivated, "especially when you have interest that wanes, and when people are getting ready to ship a game, or they have a kid, or their partner gets sick or they get sick, and all of the 100 things that come up and end up distracting them."

This is a key problem with the IGDA. It relies on volunteers, but effective advocacy requires full-time focus and sustained effort. You can't reasonably expect people to prioritize these advocacy efforts when they have day jobs in an industry notorious for prolonged crunch, and exploitation of a "passionate" work force willing to work absurd hours for lower pay than their skill set would receive in other fields. (MacLean herself said one of the industry's biggest problems is its tendency to churn out people in the first decade of their career, an issue greatly exacerbated by the treatment of junior developers.)

But the IGDA can't afford to pay people to do this work, either. According to the group's latest Form 990 filed with the IRS, it pulled in $456,000 in 2016. A little less than $300,000 of that was from membership dues, with another $104,000 from event sponsorship. This is the largest non-profit organization in the world dedicated to the creators behind a $100 billion games industry, and it brings in less than half a million a year and counts advocating for developers as just one of four major priorities on which it will spend that money.

"The IGDA is fine for what it is, but it is not an organization capable of representing the interests of game developers in the same way the ESA and other trade groups represent their employers"

MacLean's predecessor in the executive director role was compensated about $103,000, which for the person representing the creators of a $100 billion industry probably sounds like a more than reasonable fee. But it also meant the person at the top was taking up more than 20% of the IGDA's annual budget while tasked with inspiring the volunteers that make the organization run. Because what could inspire people to sacrifice their free time to the cause better than someone making a six-figure income specifically to convince people to sacrifice their free time to the cause?

It's an impossible task. And if it were possible, you probably wouldn't want to do it. MacLean touched on this in our interview, but she's essentially competing for volunteers' free time against everything else in their lives. She specifically mentioned work at animal shelters or for causes they believe in, but these people also presumably have family and friends, and no more hours in the day than you or I.

Ignoring for a moment the irony in asking developers to work long unpaid hours to fight for causes like making sure developers don't work long unpaid hours, if you're going to ask people to sacrifice their scarce free time to your organization, you'd better be damn sure their sacrifice isn't going to be wasted.

And on the advocacy front, the IGDA can't muster a reasonable argument that volunteers should expect that. MacLean pointed to crunch in the workplace as one example of an issue where the IGDA's advocacy has been successful, saying it is nowhere near as prevalent in the industry as it was a decade ago.

"There are absolutely still companies who crunch, who are very honest and transparent about it, who will continue to do it because it has helped them deliver blockbuster franchises and they believe that is the best way to make games," MacLean said. "But we are also educating game developers about the consequences of going to work for that company."

Two years ago, the IGDA pledged to name the best companies for crunch, and to name-and-shame the worst companies if they didn't shape up. Not only did they fail to name the worst abusers (which really shouldn't have been hard considering how very honest and transparent they supposedly are about it), they didn't even bother to follow through and name studios that handled crunch well.

When asked earlier this year why the group backed off its pledge, MacLean said, "After careful consideration, the IGDA thought it was important to expand their work beyond crunch and look at all of the ways in which game developers experience challenges in creating fulfilling and sustainable careers. Crunch is only one of the many challenges game developers around the world face, and the IGDA is working on a larger set of resources to help address many of the issues highlighted in the Developer Satisfaction Survey."

The IGDA is fine for what it is, but it is not an organization capable of representing the interests of game developers in the same way the ESA and other trade groups represent their employers.

"Developers need a seat at the table, and they need proper leverage to protect themselves from the rest of the industry"

We've seen developers hung out to dry by those publishers and employers too many times. Change has been slow in coming, if at all, and typically only when it makes financial sense to those larger players.

This cannot be the model going forward. Developers need a seat at the table, and they need proper leverage to protect themselves from the rest of the industry.

As CEO of 38 Studios, MacLean herself should understand better than most how tenuous the average developer's position in this industry really is, and how little recourse they have when their employer stops paying them, stops payment on their health insurance without notifying them, and neglects to pay promised moving expenses, leaving families who moved to Rhode Island for the job responsible for an overdue bill they thought had long been settled.

When asked about the studio's collapse, MacLean said that wishful thinking was to blame, that studio founder Curt Schilling "believed up until the very last moment that he was about to get funding."

Employers in this industry have an obligation to their employees not to gamble their lives and well-being on wishful thinking. If someone wants to make that bet for themselves, that's one thing. But committing hundreds of others in less advantageous positions to the same bet without so much as informing them is inexcusable. You might assume such neglect was criminal, yet no charges were filed against the people responsible.

Developers need an organization with influence and power to stand up for them, because thinking that any existing group has the interest and ability to do it--whether that's the IGDA, the ESA, or the law--is just wishful thinking.