One thing gaming could learn from Stan Lee

Quick Takes: On the late comic legend's legacy and the idea of games as a recruiting ground for hate groups

Sometimes we have points to raise and arguments to make that don't need an entire opinion column to themselves. When appropriate, we'd like to collect those mini-editorials together in a Quick Takes editorial column like this one, offering musings and observations about current events in the industry. A potpourri of punditry, if you will.

Stan's Soapbox

Marvel Comics legend Stan Lee died this week at the age of 95, and like many in the industry, I paused to consider the outsized impact he has had, on my life, on this field, and on the wider world of pop culture.

Lee had a hand in the creation of so many of our favorite modern myths, any one of which would have made him an icon in the field. Back in the '60s, Lee co-created a stable of Marvel Comics heroes that would become a modern-day pop culture pantheon, including Spider-Man, Iron Man, Thor, Black Panther, Hulk, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, the Avengers, Dr. Strange, and many of their associated villains and supporting cast.

"One throughline that bound much of Lee's work together was his willingness to use it to say something"

Beyond the colorful costumes and fantastic abilities, one throughline that bound much of Lee's work together was his willingness to use it to say something. In an era when comics were still seen as a corrupting influence on youth thanks to decades of gory horror stories and seedy crime fiction, Lee built an empire offering stories about common people who are given uncommon powers and attempt to make the world a better place. Though they featured characters with other-worldly abilities, Lee was always clear that their heroism came from their humanity, not a radioactive spider bite or a bombardment of gamma rays.

"From time to time we receive letters from readers who wonder why there's so much moralizing in our mags," Lee wrote in one of his monthly Stan's Soapbox columns. "They take great pains to point out that comics are supposed to be escapist reading and nothing more. But somehow, I can't see it that way... None of us lives in a vacuum--none of us is untouched by the everyday events about us--events which shape our stories just as they shape our lives. Sure our tales can be called escapist--but just because something's for fun, doesn't mean we have to blanket our brains while we read it!"

Lee's moralizing and messages gave his stories weight and substance. They created a foundation for other artists to come in and build on his work, refining what worked, discarding what didn't, and bringing their own meaning to the projects. There was something substantial there for other creators to engage with. Lee's works not only survived his creative departure from them; they have thrived far beyond the realm of comics.

Video games have done plenty well for themselves by asking players to "blanket our brains" for so long, but I can't help but think the industry could do a whole lot better in the long run--commercially and culturally, both in and away from games--if it were more willing to be about more than just fun.

For all of Stan Lee's influence on gaming, it saddens me that his simple willingness to stand for something has not carried through. It feels like we've missed the point.

Are games a breeding ground for hate groups?

Recently NPR ran a report on hate groups targeting video games as a fertile recruiting ground. It's an alarming prospect, and a modern twist on the age-old scary mainstream media report for older generations about video games corrupting the youth of today. It's also one that seems to be more firmly based in reality.

If you're a hate group, there's a lot to like about recruiting in the gaming space

Hate groups (and individuals who readily wave their banners) seem to be exceptionally active in games of late, with Steam regularly striking down Nazi user groups once they're reported on in the press and hate symbols finding their way into games like Destiny 2 and Scum. And as we reported last month, Discord had a staggering 1,000+ different user groups that named themselves after the same white supremacist slogan.

If you're a hate group, there's a lot to like about recruiting in the gaming space. We offer a massive audience of young men to reach, and countless tools to reach them, whether it be forums, social media platforms, in-game chat, or third-party communication tools. With a handful of exceptions, we have shown shockingly little interest in moderating these social areas or removing bad faith actors from the community. After being the subject of so many over-the-top moral panics, we're already deeply skeptical about criticisms based in any kind of morality. We're quite comfortable with violence. And top top it off, we tell people our violent games are just supposed to be fun, and not about any greater meaning.

David Cage spent a lot of time, money, and effort to make a game about an android civil rights movement in an American city with a history of racism and race riots only to repeatedly insist "there is no big message to humanity in this game." Last month, Ubisoft Massive COO Alf Condelius bluntly admitted that The Division series backs away from any political messages in its work because having political messages is bad for business. (Never mind that Tom Clancy's militaristic fantasies are inherently political and incredibly lucrative for Ubisoft for the past 20 years.)

Then there's Far Cry 5, whose villains are rural Americans with a religious fervor, enthusiasm for firearms, and a distrust of outsiders. One might think such a game had something to say about contemporary politics in America, but according to creative director Dan Hay, one would be wrong.

When you insist your game is not making any kind of statement and your only goal is to make it fun and awesome, then everything in it--including violence--is there because it helps make things fun and awesome

These developers are either lying to avoid alienating players, or arguably worse, they're telling the truth. In that case, they and the companies they work for have recognized a desire among the audience for topical content that feels relevant to the world we live in, but have not developed an appetite to try and improve that world. Instead, they treat it as window-dressing for their fiction, evoking other people's very real anxieties and suffering, then letting gamers cosplay their way through it as a theme park ride.

The most charitable way I can put it is that the AAA industry is only beginning to grow comfortable with games having messages and being criticized as creative works rather than commercial ones. And even then, only a relative handful of companies seem to be willing to admit they would dare have creative aspirations deeper than entertaining players. It's far more common for games with any budget to focus on fulfilling a specific player fantasy, to be easily digestible entertainment, to simply be fun.

There's nothing wrong with games that are fun for fun's sake, of course. And there's not necessarily anything wrong with violent games being fun. But when you insist your game is not making any kind of statement and your only goal is to make it fun and awesome, then everything in it--including violence--is there because it helps make things fun and awesome. So one message you're actually sending (and constantly reinforcing) is that violence is fun and awesome.

And who is that message going to appeal to? Who is going to most want increasingly sophisticated and photo-realistic playgrounds where they are not just permitted but encouraged to dominate people through violence (NPCs and other players alike), but can also be assured that they won't have to think about what they're doing, or why, or perhaps worst of all, be told that it is in any way bad?

I don't think video games create bigots or hate groups. But I do see why they would feel comfortable here.

More about Stan

There was one other thing I wanted to mention about Stan Lee and the meaning he put into his work. When putting together our industry reaction piece after Lee's death, I started to write about how Lee's influence cut across every demographic in the industry. So I glanced over the dozens of developer tweets I had compiled to see if that assertion held up. To my surprise, it didn't. I noticed very few of the tweets I'd seen had come from women. I don't want to read too much into that as it's a reflection of numerous factors, not the least of which was who happened to be around and on Twitter when the news broke.

Nevertheless, it got me thinking about the comic book stores I frequented as a child, and how I almost never saw girls or women in them. It got me thinking about the comics on the shelves, and how so many of them featured women as sex objects, if they featured women at all. And that bothered me because Lee was so outspokenly rejecting of hatred and bigotry, so clearly in favor of equality between all people, yet the culture that grew from his work has struggled mightily with internalizing those lessons. (It's worth noting Lee's massive body of work wasn't completely free of racism and sexism, but the overriding sentiment was clear.)

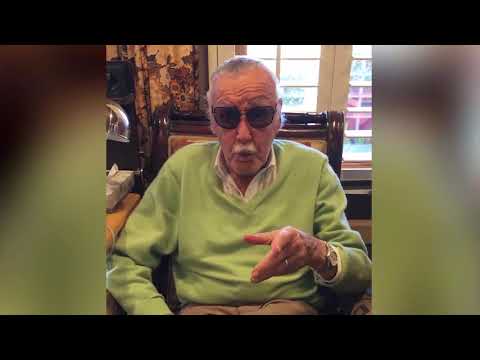

Instead, we seem to have a new regressive consumer revolt on our hands every time Marvel puts one of its white male heroes on the sidelines for a bit to let someone from an underrepresented group carry the torch. I assume this was a source of frustration for Lee, as he felt the need to remind fans where he stood in a video message from last year.

Perhaps the takeaway is that there's no need for the gaming industry to worry about putting messages in its games, because it's not entirely clear anyone is going to listen to them, anyway.