Self-regulating loot boxes is harder than it sounds

Supposing publishers even want to rein in the monetization scheme driving their bottom lines, how are they supposed to go about doing that?

There's been a call on this site and elsewhere lately for game publishers to curb their greediest tendencies when it comes to loot boxes, to self-regulate as a way to pre-empt government intervention. We've laid out arguments for self-regulation a number of times, but to be fair, we haven't gone too deep into specifically how the industry should go about doing that.

That's partly because this is an incredibly complex problem from just about any angle. Start with perhaps the most straight-forward position possible, that of a legislator in a moral panic, someone thinking only of the children. What does their legislation look like? A blanket ban on loot boxes? Sure, let's go with that. Henceforth, all loot boxes are banned.

Well, what's your legal definition of a loot box? A random grouping of in-game items available for sale? Does it need to be directly purchasable? What if it's given away with sales of virtual currency, as Activision Blizzard did to skirt Chinese loot box regulations?* Would packs of cards in a free-to-play trading card game count? Would packs of cards in a pay-once premium trading card game count? Maybe you step back and ban randomization that ties in to monetization. So how about enemies that drop randomized amounts of virtual currency that can be spent on downloadable content? Perhaps you just decide to ban the digital sale of unspecified goods. But that would seem to include DLC season passes, which are generally available around a game's launch but not fully detailed until long after.

"A loot box, much like pornography and goaltender interference in the NHL, is very much an 'I know it when I see it' sort of thing"

The point is that a loot box, much like pornography and goaltender interference in the NHL, is very much an "I know it when I see it" sort of thing. But legislators need their laws to be enforceable, and that means creating a binary distinction, clearly delineating what the law affects and what it doesn't. "I know it when I see it" legal definitions lead to problems, and those problems are compounded exponentially when you're talking about the moving target that is the games industry. First there's the ability of companies to change up their monetization to meet the letter of the law while clearly violating the spirit, as Activision Blizzard did. But on top of that, if you write a bill to cover loot boxes as implemented in May of 2018, the chances are good it won't be as applicable to the way loot boxes are implemented whenever it gets signed into law, much less when the industry's legal challenges to it taking effect are finally exhausted.

So that's the problem from the government perspective, and it only gets harder when you come at it from the position of self-regulation. Now you have all the same concerns of needing to clearly delineate what's acceptable and what isn't, but your top priority is to curb the undesirable behavior with the smallest negative financial impact to game makers.

That's complicated further by the need to address all the anger over loot boxes when that anger is difficult to boil down to a single cause. Star Wars: Battlefront II was pilloried for introducing a loot box scheme where the box contents would give players competitive advantages, yet games like FIFA Ultimate Team and Hearthstone mostly get a pass from their communities despite tying purchases and performance together more directly. The Belgian Gaming Commission said Battlefront II was fine, but found FIFA 18, Overwatch, and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive tempted and misled players with the tactics of gambling operators, expressing particular concern over their impact on children and vulnerable people. Meanwhile, Juniper Research pointed to the literal gambling scene around Counter-Strike: Global Offensive weapon skins as the research firm took the unusual step to advocate for regulation. Just how many of these concerned groups are you looking to placate here?

Keep in mind the more concerns you're trying to address with any self-regulation, the less targeted the solution is going to be. And a wider-ranging solution means more of the industry is affected, which means you're trying to get buy-in from a lot of people who are making considerable amounts of money from the status quo. Think of the most exploitive treatment of loot boxes or free-to-play mechanics you've ever heard of, and realize that a team of people managed to rationalize it to themselves as a perfectly OK thing to do. Now imagine it's been fantastically lucrative, and you need to convince them it's in their own best interests to proactively give up that revenue stream.

You also need storefronts to go along with you, something that wound up being key to fending off calls for violent game legislation in the last decade. In the '90s, the industry created the ESRB rating system, which temporarily quieted calls in the US for governmental intervention. But when the M-rated Grand Theft Auto III hit in the early 2000s and people realized retailers were selling it to children anyway, those calls got a lot louder, and the laws proposed got a lot closer to reality. Then-California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed one into law in 2005, and the ensuing legal battle dragged on to the Supreme Court in 2011 before the industry finally claimed victory. In the Supreme Court's decision, Justice Antonin Scalia specifically pointed to then-strong retailer enforcement of the ESRB system as evidence that California didn't actually need its legislation enough to limit publishers' rights to free speech.

"Where does a streamlined interface end and a manipulative monetization technique begin?"

So whatever you decide, you need Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft, Google, and Apple to agree to do their part in keeping the egregious loot boxes off their storefronts (and forsaking the considerable revenue they'd get from all those sales). And you also need Valve--not an ESA member, I'll point out--to go along with them, because how hard could it be to get this sort of cooperation from an absurdly successful company with such little regard for consumer protection laws that they spent four years fighting Australia over their refund policy and refusing to pay a meager (for Valve) $3 million fine?

It's even trickier than that. At least with violent video games, they generally are what they are. Very few games become noticeably more or less violent months and years after launch. But with loot boxes, you're dealing with games that are constantly, constantly tweaking their mechanics. So assuming you come up with good rules for self-regulation, when and how are they applied? Are the storefronts responsible for keeping violators off their platforms? Do they check for violations at submission? At every update? Do you set up an ESRB-like body to classify the games and approve them for sale? Who pays for that? Is that even possible with a business model reliant on a plethora of games constantly launching, patching, and updating? Would a free, self-reporting system like the ESRB uses for rating digital releases be reliable for loot box regulations?

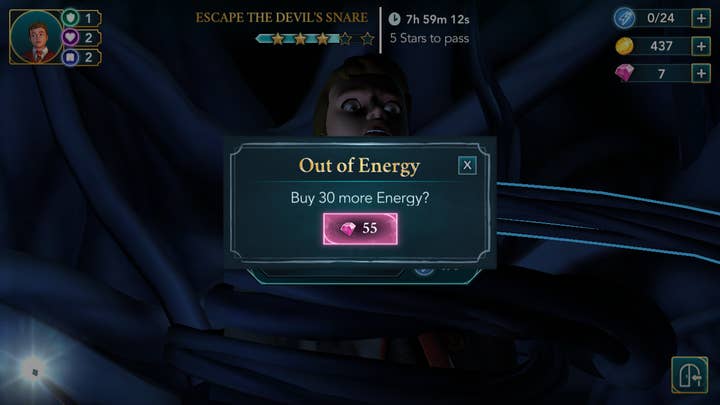

How about the specific monetization techniques? Some of the outrage over loot boxes comes from the way they aggressively manipulate players into spending more. Do we need to detail each and every one of those? What about changes made through A/B testing that seem to drive up revenues even if we can't really articulate why? Where does a streamlined interface end and a manipulative monetization technique begin? Would you forbid something like the Harry Potter mobile game asphyxiating a child on-screen unless the player pays to free them immediately? It's the sort of thing that gives games a horrible reputation and makes parents distrust the industry, but it's not a loot box.

Maybe you create the equivalent of an industry gambling commission to ensure players are given accurate information about their odds, and that companies aren't playing shell games to squeeze more money from them. How do they ensure compliance? Do they get access to the code of every version of every game? Do they rely on players to flag games with suspicious mechanics? How do you get the multitude of publishers in a traditionally paranoid industry to buy into that sort of transparency?

There's a great bit of game developer advice that goes something along the lines of "Always listen when your players tell you what problems your game has. Never listen when they tell you how to fix it."

The players, the press, and the politicians have all told the industry what the problem is. Now it's up to the industry to fix it.

*I've brought this up before when talking about loot boxes and I will continue to do so because I can think of few actions so detrimental to the industry as having one of our largest and most prominent players pull such an obviously underhanded bad faith end-around to avoid having to reveal the odds customers are getting in their loot box purchases, something any reputable company should be doing of its own volition.