Digital Foundry's guide to games media assets

Maximising the impact of screens and trailers

Flashback to 1999. Computec Media UK is in the process of readying PlayStation World magazine and the editorial team I am leading is presenting dummy pages and concepts to focus groups assembled by market researchers MORI.

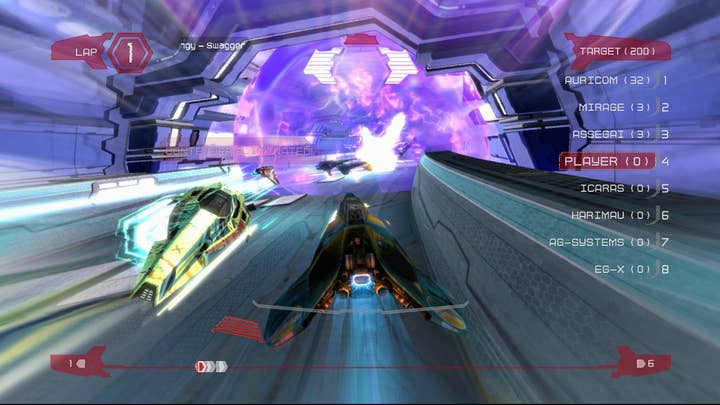

Part of the approach back then was to put serious thought into the way screenshots would be used in the magazine: custom framegrabbers were ordered to get the best possible image quality and the brief given to the editorial staff was simple - to capture the defining moments of every game we review in those screenshots. Our aim was to capture the essence of gaming on the page, to make the pastime seem as fun, enjoyable and exciting as possible. The results of this approach were acknowledged in our focus group testing: screenshots were actually more important to our readers than the text in showcasing the software.

You can spend days faffing around posing models, getting the camera just so and all that, but personally I've always been a fan of showing something real

Steve Lycett, Sumo Digital

In putting this feature together, it occurred to me that the lessons learned back then, combined with the utilisation of today's capture technology would make for an interesting guide for developers and publishers in how to create the most dynamic, exciting and relevant media assets. Back in 1999 we wanted to use screenshots (and subsequent to that, video via covermounted DVDs) to show gameplay at its best - and I daresay that this is also the objective of game-makers looking to make their products as exciting as possible.

In this piece I'll be covering off the Digital Foundry approach to the acquisition of screenshots and then turning the focus onto game trailers. No-one knows better than the developer what content to include in these productions; instead I'll be covering the technical issues in making your presentations look as good as possible when they hit the internet.

Right now there are many different ways in which screenshots are created: carefully posed in-engine framebuffer dumps and paused gameplay with custom camera angles are two favourite techniques. Entire features have been written about how the majority of screenshots put out there are being carefully prepared and in many situations are not representative of the final product, but perhaps the real issue here is whether those precious, genuine moments of gameplay magic are being captured and transmitted to the intended audience.

Back in the day, the traditional technique of using framebuffer dumps was a bit of a no-brainer - analogue outputs will never match the digital precision of extracting your assets straight from VRAM, and the resolution of the PS1 and PS2 eras was such that offline upscaling made sense: the alternative was horrifically jaggy blown-up images that looked especially poor in print. CRT monitors also had a way and blending and blurring gameplay graphics, making untouched framegrabber shots quite misrepresentative of the way the game would be viewed.

Things have changed in the era of the HD console. LCD panels have replaced the CRT, every HD console comes with the digital precision of an HDMI output and most games media is now consumed over the internet - again, mostly on flatscreen displays. Where most framegrabbers never used to be up to the job of producing pro-level marketing assets, today's HDMI capture cards definitely are when utilised correctly, and the entry-level offerings make upgrading an existing PC into a recording station a relatively cheap operation.

So, why make the change at all? On console at least, the bespoke framebuffer dumping tools for console platforms (Xbox Neighborhood in particular) are rather clumsy and unwieldy, relying on the user to press the "grab" button at exactly the right time: a torturous procedure that rarely yields dynamic results.

The advantage of shifting to HD capture is simple: every single frame to issue from the source hardware is recorded, allowing you to go back, review and pick out the exact frame that gives the most dynamic representation of gameplay. You'd be surprised at how much can happen in 1/60th of a second.

Some of the developers Digital Foundry has worked with already use this approach.

"Typically we want to get screenshots that convey the impression of what it's like to actually play the game. You can spend days faffing around posing models, getting the camera just so and all that, but personally I've always been a fan of showing something real," says Sumo Digital's Steve Lycett.

"We'll generally set up a multiplayer game, rig one of the machines to be captured and get down to playing the game, making sure to not hold back! Once we're done swearing at each other, we'll run through the footage, pick out those special moments everyone loves, say where I've taken out one of the test team with a particularly nicely placed shot and passed them just before the finish line to steal the win. Then not only do I have some nice real game action screens to use, I can also rub someone's face into the fact that not only have I beat them, but it's on the web for all to see."

As Lycett points out, there are other crucial advantages aside from the dynamic nature of the shots being generated: by releasing screenshots derived from actual gameplay, you are giving the audience a more authentic, honest look at the product you want them to buy and from my experience, the core gamer audience in particular will appreciate that.