"No adaptation without interpretation" -- turning Animal Farm into a game

Imre Jele on why he believes audiences are ready for more games about politics and critical thinking

Nothing happens before its time, as they say. And if there was ever a need for a video game adaptation of George Orwell's Animal Farm, now is surely the moment.

Orwell's celebrated fiction is an allegory on the rise of dictators, and its examination of inequality, power and manipulation is frighteningly relevant today. This is something that creative director Imre Jele, and his indie development collective at The Dairymen and Nerial, are well aware of, and they're determined to use the medium of video games to bring this classic to even more people.

"It's painfully relevant -- we felt that we have a responsibility to bring it in front of people," says Jele, when we asked why he chose to take on the daunting challenging of adapting the 75 year-old book into a narrative adventure game for desktop and mobile platforms. "It is more than just entertainment. It is important [for it] to be in front of people, so people can ask questions about their governance."

Jele isn't afraid to talk politics, and with good reason. He grew up in Hungary, when the country was still under communist rule -- "I was the last generation who still clapped for the big leader." In the eyes of the regime, his family was on the "wrong side of politics", he says, and Animal Farm was one of three stories his grandparents read to him regularly when he was young. Over time, his appreciation of Orwell's novel steadily increased.

"As I grew up, I started to understand that it wasn't just a sad story. It is much more than that. It's representative of the oppressive regime I grew up in, so that's one of the reasons I wanted to make it. It's just personally important to me, and so it is for the rest of the team. It's just an important book to us emotionally."

Adapting Animal Farm into a game has been an ambition of Jele's for decades. Originally, Jele and The Dairymen co-founder Andy Payne wanted to ship their Animal Farm game in time for the 2016 US election. But before they could begin to tackle the task of turning plot points into gameplay, they needed to convince the Orwell Estate that this was a worthy endeavour in the first place -- and that they were the right people to do it.

After penning a series of heartfelt letters, Jele was able to meet with Bill Hamilton, head of the Orwell Estate, and the person charged with guarding the writer's legacy. Given the litany of sub-par adaptations of books to other media, you'd be forgiven for being surprised that the Orwell Estate gave Jele and his team the go-ahead at all. But Jele says convincing Hamilton wasn't difficult. Far from it.

"He wanted to understand our creative goals," says Jele. "One of the early questions he asked is: how do you want to change Animal Farm? My answer was 'Look, I have nothing against someone creating Animal Farm 2: Electric Boogaloo. That's fine. But that's not what we want to do.' What we wanted to do is a faithful adaptation."

With the endorsement of the Orwell Estate, the team set to work experimenting with designs. Jele felt Animal Farm was more suitable to be adapted into a game than Orwell's other famous works, such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, because "a farm works in systems. You plant a seed, you take care of it, something grows out, and you harvest it... It just felt like it translates itself to a very systemic game design." Furthermore, the animals themselves fit different archetypes or classes. Boxer the horse is strong, the cows provide milk, and so on.

"How wonderful would it be if we could make some people think about life in a new way after playing the game?"

In practice, however, it didn't prove to be so simple. They tried adapting elements of the story in different ways, including putting players in control of one of the pigs -- the farm's self-appointed leading class.

"At some point, I remember thinking that we hit another wall, and I felt that I would rather not do this game if I can't do it right," Jele says.

That was when Payne suggested that Jele reach out to Nerial -- makers of the ingenious strategy series Reigns, which is a game he kept bringing up during their prototyping phase. Jele's admiration for the game led him to contact Nerial design director Francois Alliot and CEO Tamara Alliot.

"I just wanted to talk to him to get advice, and he was like: 'Oh, can we get involved?'," he says. "Everyone just got super excited, and it went from getting advice to getting them to actually be the development partner, and they made a fantastic contribution. And that story repeated itself and everyone we spoke with."

Soon, the team was joined by Failbetter Games creative director Emily Short, who has adapted Orwell's text specifically for the game. Meanwhile, Abubakar Salim, who starred as Bayek in Assassin's Creed: Origins, plays the all-knowing narrator.

"Everyone felt that this is such an amazing creative opportunity that they just jumped onboard. Honestly, the game would not be this good without them."

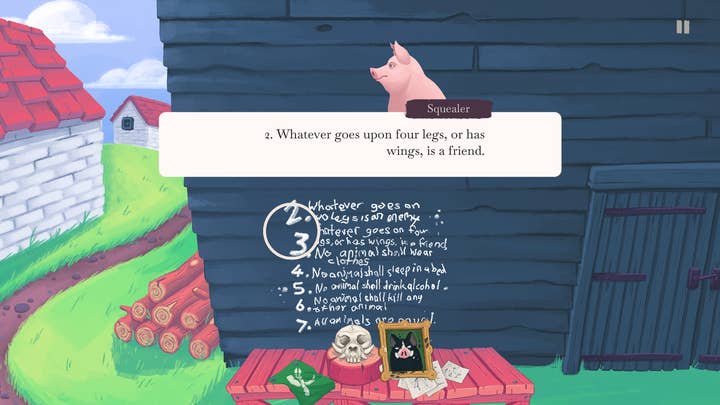

Together, the team has created an experience that marries narrative and strategy simulation. In the game, players choose which animals to side with -- the Stalin-inspired Napoleon or Trotsky-esque Snowball -- and must decide which animals to cultivate, to subvert, or sacrifice, as they manage the farm.

The real challenge is walking the line between dictatorship and uprising -- perfect ground for player choice, then, but a design that risks losing sight of Orwell's original message. But while the team naturally added elements, and offer several different endings, Jele says they have purposefully avoided "justifying oppression."

"The way I see it, there is no adaptation without interpretation," he says. "Even just reading a book, you see something else that I didn't, so it's very difficult not to add yourself. But our goal was to [avoid that]. To [stop] every time we catch ourselves doing that, go back to the basics, and say: 'What would Orwell have done?'

"The reason being is we felt this is not our moment to add our own political perspective or our own view on the words. Our goal is to take something which has stood the test of time for 75 years and just allow it to do its job, and the adaptation we added was specifically to make it fit the interactive form -- which, of course, requires more content."

"Our goal is to take something which has stood the test of time for 75 years and just allow it to do its job"

Those additions have been carefully extracted from stories that are implied, but never directly told. For instance, in the original book, the pigs used the birds to spy on neighbouring farms. In Nerial's adaptation, the pigs also use the birds to spy on their own animals.

"Clearly they [the pigs] don't think highly of them," says Jele. "They're very antagonistic. Of course, they would use the birds to spy on other animals."

Given the distrusting nature of the pigs and Orwell's own examples of life in a surveillance state, particularly in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Jele feels this reflection of mass surveillance keeps the game close to the author's politically-aware prose. And, for each new addition, that process repeated throughout development.

Like any creative, Jele and his team hope that their version of Animal Farm will be fondly remembered by those who play it. But most importantly, Jele wants players to understand Orwell and his political fiction: "Our goals are, of course, entertainment, but it's also a form of art. And when it comes to Animal Farm, as Orwell himself said, there is no such thing as something being non-political. It cannot been non-political -- it is a political fiction."

Taking on this lofty responsibility was "both inspiring and humbling, but also terrifying," he says. Even so, segments of the audience have been resistant to games maturing beyond their roots of action and conflict, and becoming a medium where politics and other complex issues can be explored. Does Jele believe today's audience is ready for a game of this kind?

"I think we are ready as an audience, as a form of media, as a form of art, and I believe we were ready as developers," he says. He cites Papers Please, Thomas Was Alone and the work of The Chinese Room as examples of how dramatically games have changes in the last 20 years.

"Now we have other subjects to talk about and there is an audience. And thanks to digital distribution, you're not limited to only making blockbusters. Now you can do real art, because you can reach your audience directly.

"So I believe that there is a place for these kind of more artistic pieces. And what we've tried to do is to make it in a way that you can enjoy, even if you don't want to get lost. Even if you're not a gamer you can enjoy it. And if you're a gamer, you can figure out the mechanics behind it... I don't think that art has to be in the way of entertainment."

Right now, Jele won't be drawn on whether Orwell's other works could receive similar interactive adaptations. But his passionate evangelism has already impressed the organisers of the Orwell Youth Prize. The annual programme seeks to amplify the work of politically engaged young writers, and the organisers have agreed to add a game design category in the hopes that more young people will be attracted to apply because of the opportunity to write for a medium they already love.

For The Dairymen and Nerial, using games to encourage people to think more deeply could not be more important at this complicated time in history. That's a view that others will share and, with any luck, this promising narrative adventure game could be the start of critical conversations, just like its source material.

"The ultimate goal is: if I can leave someone looking up from the game and going, 'Ha, You know what, that character reminds me of someone I know'. Or 'that character reminds me of a politician I just listened to yesterday'. If I can get them to ask the question, if I can make them start their critical thinking [about] their governance, that would be an insane achievement," Jele concludes.

"I know it's a hugely ambitious, potentially obnoxious goal, but it is something that was on our mind. How wonderful would it be if we could make some people think about life in a new way after playing the game?"