"Netflix of games" a threat to developers

If subscription streaming services take off, creators likely to lose leverage in dealing with platform holders

Downloadable subscription game services and on-demand game streaming are not new. The former has been around in one form or another since the early 1980s. The latter is almost a decade old already.

But what is new is the fervor with which the industry has been pursuing both ideas of late. Sony has had both on the PlayStation family of systems for years. Microsoft and Electronic Arts have their own subscriptions and both announced plans for streaming services at E3. Smaller publishers like Capcom are testing out streaming, and an assortment of start-ups like Hatch, Jump, Utomik, and PlayKey have also joined the field. Google is rumored to be muscling in on game streaming as well. Amazon has tested out subscriptions with Twitch Prime, and would anyone be surprised by a jump into on-demand streaming as well?

There remain a number of non-trivial challenges for these companies, some technical and some financial. We've covered those in the past on this site, but one thing we haven't talked about as much is the threat a "Netflix of Games" poses for game developers.

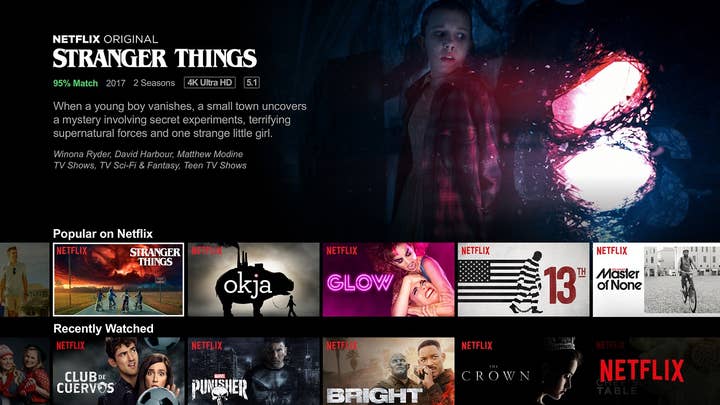

Many aspects of that threat are dependent on what form these future streaming platforms take. Look at discoverability, for example. An industry-reshaping streaming platform set up like Netflix--where you can only find things by searching for the title or browsing endlessly through an algorithm's idea of what you might like--would have particularly concerning implications for small creators. And if that platform holder were also a content creator weighting the algorithm toward its own efforts, the negative effects to small developers could multiply like Netflix Originals recommendations.

And what happens to user mods in a world of streaming games? Perhaps there's a technical solution where the platform can let players turn on and off the mods they want, but then there's the question of which mods would be approved and offered to players, and how the platform holder could monetize them to justify the hassle.

But for developers, the biggest concern I have at the moment is funding. It's already difficult enough to find backing for development, but the investments made in smaller titles--whether by boot-strapping developers or angel investors--are often predicated on the idea that their investment may one day see a return. That's always going to be a gamble for independent developers, but if streaming subscription services become the norm in the industry, those odds are going to get increasingly intimidating.

"The more successful streaming subscription services are, the more they will undermine developers' already limited leverage in dealing with platform holders"

Even if subscription services and on-demand game streaming take off in a big way, massively expanding the gaming audience and increasing the overall amount of money pouring into games, I don't see developers being well positioned to benefit from it. To the contrary, the more successful streaming subscription services are, the more they will undermine developers' already limited leverage in dealing with platform holders.

When working with a digital storefront, developers know how many copies they sell and how much they're charging for those copies. That makes figuring out how much money a game brought in a straight-forward process. Platform holders and creators may argue about how to split the pie, but at least they can more or less agree on how big the pie is.

Compare that to subscription services, where the metrics a developer has for their game's performance will likely be limited to the number of times it was downloaded/streamed, or perhaps cumulative and average time spent playing. If companies use Netflix as a model (and why wouldn't they, at this point?), developers may not even have access to those except through third-party solutions with questionable accuracy.

Even if platforms do give developers the metrics for their own games, those numbers alone don't give accurate insight into how much money a given game has brought in. Generally speaking, they are poor ways to assign value, as a beloved niche simulator game may not generate huge download numbers but could be reason enough for its modest audience to stay subscribed long-term, even if they never touch another title. On the other hand, if payments are tied to time spent playing, the platform favors games designed as engagement engines and disadvantages more finite experiences from Undertale to Uncharted, which wouldn't be ideal for either developers or platform holders.

Regardless, the only party who will be well positioned to determine the value of a given game to a streaming subscription platform is the platform holder, because only the platform holder can put those numbers in the context of the streaming service as a whole. How impressive were those numbers relative to other games? Did the addition of the game to the catalog drive new subscriptions? How many people would be a risk to cancel their subscriptions if this game were no longer available?

With limited information, the developer cannot hope to answer these questions as well as the platform holder. So when it comes time to negotiate terms, the platform holders have an incredible advantage. Better than anyone else, they will know the value an individual game or a slate of games can bring to their service. All the developer knows is how much they think they need to keep the lights on. The worst case scenario here may be the music industry, where even the most successful of artists routinely complain of insulting royalty checks from streaming services.

A new report from Citi GPS this month determined that of the US music industry's $43 billion in revenue, artists only pocket 12%, with the rest of the money going to the various middlemen between themselves and the audience. While this is actually up from the artists' share of just 7% in 2000, the report makes it clear that growth isn't coming from streaming services; it's instead coming from concerts, a revenue stream with no clear parallel for game developers.

"The danger comes when these services shift from a secondary sales window to the primary way the audience plays its games."

Of course, we already have gaming subscription services that aren't streaming--complete with the same information asymmetry between platforms and developers--but we don't have a steady drumbeat of artists complaining about how exploitive they are. It's possible that's because to this point, those services have largely served as a secondary sales window for the industry. Much like bundles, they have been seen as a way for companies to squeeze some extra revenue out of a game that had already sold the majority of whatever it would sell as a stand-alone title. If a developer gets taken to the cleaners on such a deal, well, it might have been viewed as ancillary revenue anyway. Or perhaps it could be justified as a way to raise a game's profile, boost the number of online players, or provide some other less tangible benefit.

The danger comes when these services shift from a secondary sales window to the primary way the audience plays its games. Concerningly for developers, platform holders have shown a desire to do exactly that. Microsoft added first-party exclusives to its Game Pass program earlier this year, and has followed that up with a few third-party titles as well. Meanwhile, EA's Origin Access Premier subscription service for PC is giving subscribers frontline titles like Madden NFL 19, Battlefield V, and Anthem a week before their general release dates.

If new release AAA games become the standard for subscription services, they become exponentially more appealing to a broader audience of players. If platform holders can tackle the (admittedly considerable) technical challenges associated with streaming, their convenience factor increases exponentially. If both things happen, I see no reason players wouldn't let such services become the primary way they play console and PC games. Much as purists might decry the latency inherent to any streaming solution, there likely exists a broader audience willing to compromise the experience in the name of expedience. (Personally, I love movies yet I've still watched something on Netflix knowing it would have occasional compression artifacts rather than locate the Blu-ray copy I actually own and put it into the console.)

The companies investing in streaming services for the future are not doing so with the intent of simply monetizing forgotten bits of their back catalogs. They are looking to be first movers in the next industry disruption. They want to be for game streaming what Steam has been for PC gaming. They want to be a Netflix or a Spotify. They want to be the gatekeeper every developer feels obligated to deal with because their platform is where the audience is.

If they can do that, it will be great for them, obviously. It may even be great for gamers, as they'll be able to keep up with the latest blockbusters for a fraction of the price it would cost today. But it could be disastrous for creators, and make the idea of a sustainable career in independent game development seem like that much more of a pipe dream.