Adventures in Virtual Reality

Three developers discuss VR development for first-person adventure games

Like any nascent technology, VR brings a slew of challenges to make its potential accomplishments a little more interesting. For hardware developers, these have primarily manifested in the form of fidelity, motion sickness and cost, with the various solutions on the consumer market all taking differently prioritised approaches.

Game makers share some of the same issues. Preventing discomfort is perhaps the primary concern for most, with movement mechanics and camera control generally needing a complete overhaul for anyone used to working on screens. Of course, some genres are easier than others, with seated experiences sidestepping many of the medium's trickier problems. Still, some devs are happy to take on the challenges of working on games for which those challenges are inescapable, so we spoke to three studios who have worked on first-person adventure games in VR to ask if it was all worth it.

nDreams' Jamie Whitworth, game director of multi-platform VR release The Assembly, agrees that movement and camera restrictions were tough challenges, but says that the rest of development actually followed fairly naturally.

"Our main challenge was to create a game that allowed first time VR players to freely navigate our environments without suffering from cybersickness," he explains. "Once we nailed that, it was pretty much usual development fare for designing and creating engaging scenarios or locations in which players would want to spend their time exploring. That's not to dismiss the challenge involved in creating that world! However, for those who have worked on story-driven, narrative-focused titles before and are moving to VR, it feels like all the challenges beyond controls are in the smaller details than the broader strokes.

"When telling a story, the real challenge is to find what is specific to the media you are using"

Flavio Parenti, Untold Games

"When it comes to the player's attention, we can't forcefully direct it, but we can track it. We invested time and provided players with lots of bespoke information or visual clues depending on where they are looking at critical moments. Even something as simple as a phone screen flashing when a phone rings helps draw players towards important locations."

Flavio Parenti is the CEO of Untold Games, which recently launched Loading: Human alongside PSVR. Whilst he acknowledges that any medium has its challenges, we're really too early on in VR's journey to say whether it's any harder than anything else.

"When telling a story, the real challenge is to find what is specific to the media you are using," he says. "If you are doing a play in theatre, the storytelling - writing, direction, etc - will be very different than the one of a movie or a VR experience. I like to see VR as a medium that merges immersive theatre, the creative power of digital imagery and the gamification of videogames. VR is still in its infancy, so the rules need to be discovered while producing for the market. It's a complicated process that involves all the aspects of a VR experience, from locomotion, to interaction design.

"As an example, in the ending of Loading Human, we used a technique that comes from the movies - which is to intercut the ending with the credits. It's very effective, but we found out about the effectiveness of the idea only after we developed it. It's a trial and error process whose purpose is to define the rules of VR."

For Jakub Mikyska at Grip Digital, there was a different challenge. Their game, The Solus Project, had already launched as a traditional first-person adventure title on PC, so porting to VR meant rethinking some existing ideas. Coming to the decision to do so was a natural consequence of the nature of the game.

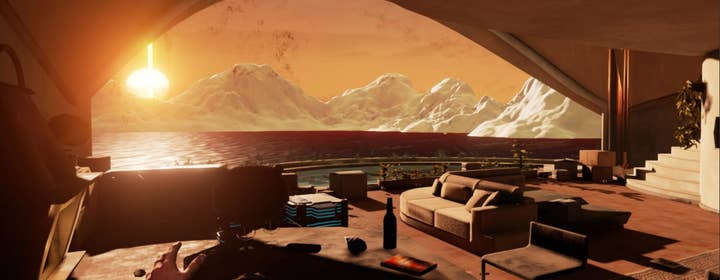

"The Solus Project was always about immersion, about 'being there'. The game was in development for three years and I would say that the technology managed to catch up with the vision for the game while we were working on it. So, it was never a question of whether Solus is going to be a great VR experience. It was just about figuring out the stuff that everyone else who is looking into VR is trying to figure out: how to handle menus, text, movement.

"We knew that exploration, immersion and atmosphere are going to be better suited for VR than, let's say action games. And what we have made really does stand out from the crowd of other VR games at the moment. You can spend about 15 hours on the main story mode and countless hours just exploring the vast, open archipelago and cave systems that make the game. In the time where most other VR games are still more like short experiences, or 3-hours games asking for an AAA price, Solus combines linear storytelling with completely open 'go anywhere, see what you want, explore' attitude. VR is something that adds another dimension to the game."

"The game was in development for three years and I would say that the technology managed to catch up with the vision for the game while we were working on it"

Jakub Mikyska, Grip Digital

In terms of player movement, both nDreams and Grip offer the player a choice of styles - between 'teleportation' and the smooth analogue movement of TV gaming for "those who don't get motion sick." In The Assembly at least, Whitworth says that players have overwhelmingly opted to go for the safe option, something he says has contributed to longer playing sessions.

"Roughly 90% of our players in VR are sticking to the default Blink mode. Both systems allow for full and accurate movement around our environments, but Blink mode is great for those who are susceptible to cybersickness when playing in VR and for those who don't have the dexterity to handle movement and rotation across two analogue sticks. The latter can be overlooked when the first wave of VR hardware caters for a largely hardcore, early-adopter community.

"We've had a lot of feedback from players who were able to spend more time playing The Assembly than other titles because of the benefits of Blink Mode. I wouldn't say that shorter play sessions are detrimental to The Assembly: we deliberately paced our game around small locations that the player could nip in and out of. But if you're developing an intense experience in VR, it's worth considering breaking your levels or encounters down into sizeable chunks that allow the player to take breaks in sync with the ebbs and flows of the game's pace, so as not to force them to quit in the middle of the action in order to take a rest."

Untold decided to adopt a more hybridised system of movement for Loading: Human, which Parenti is still happy with, but stresses that experimental nature of.

"We are happy with the choice, and looking forward to improving it. It is important that we all understand how early this tech is. In Loading Human, we tried to give the player the most freedom possible, thus we avoided teleportation (in order to keep a strong sense of presence), and any 'fixed rail' kind of experience as well. This forced us to find a system that enabled free roaming without giving any nausea. The point and go system is a first step toward the right direction, and we are aware that many improvements can and will be made."

In terms of how that affects playtime - perhaps a more serious consideration in a game where the player is following a complex narrative - Parenti says that you can compare VR usecases to TV. Bookend experiences in the same way TV shows do and you won't go far wrong.

"It pretty much depends on what we call 'small chunks'," he says when asked about session times. "A TV series episode could actually be categorised as small if it's compared to a full feature movie. But then a movie is small if compared to a full season, let alone an entire TV series, which sometimes reach six to seven seasons. I'd say that the goal is to understand what is the VR sweet spot for the player. In Loading Human, each episode is divided into a 45 minute fragment. This way, if the player needs to take a break, they can, without breaking the narrative. It seems to be a good balance, but we are studying the players' feedback to gather some more information about it."

Mikyska agrees that flexibility is key, although The Solus Project hasn't been broken into chunks in the same formal way. By offering both VR and 'regular' versions of the game, the CEO hopes to find something which suits everyone.

"Everyone's experience with VR is a little different," he says. "There are people who can spend hours in and there are people who can't stand VR at all. The Solus Project is a relatively peaceful game that encourages players to explore it at their own pace. It is quite easy on the eyes, does not require quick sudden movements...it is not what people would call an 'intense' experience. So, we believe that extended sessions with The Solus Project will be OK for most people. But there is always the option to drop the VR headset and just enjoy the game on a TV as well."

"for VR as whole, it [roomscale] offers us a step towards our holy grail - an interface with a virtual world that feels and responds as the physical world does"

Jamie Whitworth, nDreams

The last key divide in the VR space is the approach to the player's surroundings. As anyone who's tried the Vive in a well thought through set up, the effects of room scale VR are truly incredible, but as anyone who has one at home will testify to, it's also not the most convenient device in any but the largest houses. All three of our developers are excited by the prospect of room scale consumer VR, but equally realistic about its chances of mainstream success.

"The VR of today is the first step of the journey to the holodeck," says Mikyska. "So, a room-scale VR is exciting, but it certainly isn't a consumer-facing thing, more like an entertainment park attraction. But the idea is interesting. Combining movement in the virtual world, combined with the movement in the real world can not only remove the sickness that some people feel in VR, but can offer another level of immersion.

"But we are far from there, yet. As long as we need the headsets connected with cords to the PC and power, room-scale VR is just not practical. But wireless technology will come. For now, I believe the most important task is to make VR work. Technologically, as well as financially."

Parenti agrees. "Room scale is a lot of fun, but it is very demanding. You need an empty room to play, and you must also have the desire to play standing. I strongly believe that most of the players or audience like to sit in order to enjoy things like games, movies, stories, books, etc. I can see room scale as a perfect fit for arcade VR, and hardcore VR gamers, but it's not for everyone. And sooner or later, every developer has to deal with the market."

Of the three, nDreams' Whitworth is perhaps the most optimistic about what room scale can offer, although he does note one particular drawback...

"For The Assembly, room scale doesn't offer much, as we're a gamepad first experience. But for VR as whole, it offers us a step towards our holy grail - an interface with a virtual world that feels and responds as the physical world does. This not only increases the sense of presence for the player, but allows them to act in the virtual world as they would in the real world, which can offer more scope for player led improvisation and reward it appropriately. This is hard to do when players are relying on abstract mechanics to govern complex behaviours, especially when those abstractions simplify complex actions into digital on/off actions.

"A great and common example of the advantages of room-scale can be seen when stealth game players are free to use their head, legs and body in tandem to peak around corners at any speed, distance, angle or height. If anyone has had the chance to play Budget Cuts or Alien: Isolation (with the VR hack) then it feels light years ahead of systems where leaning is controlled by juggling multiple buttons, keys and/or joysticks.

"But...It also means I should start getting leaner too. I can't ask for more physical participation from audiences for our games without getting involved myself!"