Combating tribalism and reducing bias in Persuasion Invasion

Colgate University's Nick Diana discusses his experimental title and new ways video games can inspire empathy

Tribalism is on the rise. Across the globe, countries and their populaces are falling prey to nationalism and "us vs them" mentalities. In the United States, studies have shown an increase in partisan antipathy as people see those with other viewpoints as less human, lacking deep feeling, rather than just having a difference of opinion.

While there is no easy answer to this growing problem, video games are uniquely suited to combat it. Games such as The Last of Us Part 2 call on players to take on the perspective of someone they hate and see the human behind the trauma.

What The Last of Us accomplishes has a technical term: perspective taking. Teachers and civic educators use this method to get students to understand why people hold opinions different from their own. For instance, asking a student who is pro-choice to write a pro-life speech is perspective taking.

The problem with the method is that it's hard to scale since one has to adapt the instruction to the individual. And that is why video games are special: they induce perspective taking on a large scale, despite lacking the individualization that occurs during bespoke instruction.

But what if a video game could have the individualization of instruction and tailor the interactive experience to the beliefs and values of the player? It's a complex proposition, but researchers at Carnegie Mellon have created a learning system, known as Value Adaptive Instruction or VAI, that may make it possible.

Initially, Nick Diana, an assistant professor of computer science at Colgate University and the researcher who headed Carnegie Mellon's VAI projects, believed that improving civil discourse depended on correcting people's logic but he eventually realized that the problem ran deeper.

"I had been doing some work on informal logical fallacies and a colleague pointed me to Moral Foundations Theory, which helped me realize that the problems in civil discourse are not going to be solved with training in logical fallacies," Diana says. "The problem was more fundamental -- rooted in our values and biases."

Moral Foundations Theory, which inspired Diana and his team, argues that our beliefs arise from a set of core values. The version used by Diana states that there are five foundational values: fairness, care, sanctity, authority, and loyalty. While these values are all shared by everyone, according to the theory, they are weighted differently with people prioritizing certain values over others. To describe how this works, Diana offers an example concerning the contrasts between liberals and conservatives.

"A lot of Moral Foundation Theory work has looked at liberals and conservatives and how they weigh these different values when making judgments. They've generally found that liberals tend to value the care foundation and the fairness foundation, and then don't weigh as much loyalty, authority and sanctity. Conservatives tend to value care and fairness a little less than liberals, but pretty much value all of the foundations equally, so they have a kind of broader palate of values that you can appeal to."

The problem that arises from our values is that when we analyze an argument or assess a situation, our critical thinking is not purely logical and is filtered by these values, creating bias.

"The extent to which you think critically about some content you're consuming depends on (the relationship between your values and the values latent in the text), so if you read something that aligns with your values, you're more likely to kind of blindly accept it as true versus if you read something that contradicts your values or world view; you're going to really think about it critically and try to figure out why it's false," Diana adds. "In civics instruction, this is called Myside bias."

"Imagine a game developing an understanding of the player's values, and when it comes to a pivotal betrayal in the storyline, adaptively choosing the villain's action in a way that maximizes feelings of anger or disgust"

With this understanding of values and bias, Diana and his fellow researchers set out to create a scalable system that could account not only for an individual's values and the values inherent in whatever content is being considered but also the dynamic way in which these sets of values relate to one-another.

"So, in our work, what we thought was... we're not gonna be as good as an expert teacher in figuring out what kind of beliefs students have, but what if we were good enough and what if we could kind of model student values using social psychology concepts, and then model the values latent in text using artificial intelligence, natural language processing," Diana explains. "Then, if we can relate those two sets of values together, maybe we can get an idea for this kind of dynamic relationship that can dictate the way you think, the way you process information."

The end result of their work was Value Adaptive Instruction, a system of learning they put to work in an experimental video game called Persuasion Invasion.

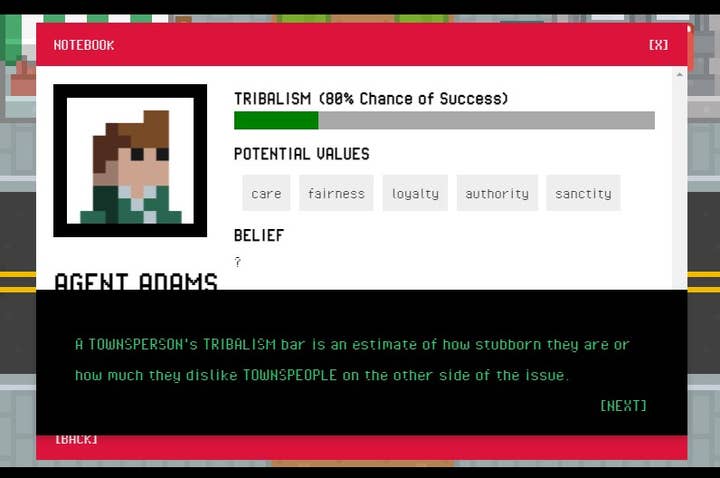

In Persuasion Invasion, aliens invade earth and, rather than using violence to conquer humanity, they sow discord in communities. To combat this threat, players take on the role of an FBI agent who must bring people together through civil discourse. The intent is not to convince anyone of a particular viewpoint but rather to just get them talking to each other. To accomplish this, players utilize discourse cards to simulate conversation whereby they can learn NPCs' beliefs in order to discern their values. Once the player believes they know a NPC's core value, they can attempt to persuade them to take part in discourse by presenting them with an argument from the other side that utilizes their core value, thereby showing them that they share the same values with those they disagree with.

This immediate gameplay requires active perspective taking as players must consider beliefs founded in another's values. However, the game's educational mechanics go much deeper as VAI is utilized to directly engage player bias.

Before playing the game, players must take the Moral Foundation Questionnaire. Players' answers, according to Diana, create "a vector of value weight which is a kind of signature of this particular (player's) value structure: the things that they care about." Then the AI behind Persuasion Invasion uses cosine similarity to compare the resulting scores against the latent values within the various arguments offered throughout the game, which are discovered via a form of natural language processing called Distributed Dictionary Representations. Upon comparing these value signatures, the AI prepares the necessary interventions whereby the player can be made aware of the arguments they are biased to. (For a complete breakdown of how these processes work, take a look at this academic article written by Diana and his team about VAI).

The VAI intervention manifests in Persuasion Invasion when the player attempts to persuade an NPC. The AI, using the previously described processes, highlights the argument the player will be positively inclined towards and warns them of potential bias. For example, one of the conflicts in Persuasion Invasion involves whether or not to turn a cemetery into a garden. If the player is someone who prioritizes sanctity, a value tied to religion and notions of purity, then said player will probably find arguments grounded in sanctity compelling. So, when presented with arguments to offer a townsperson, the player may be biased towards the option that relays the opinions of the local religious leaders. Thus, the AI responds by marking that argument.

"There are some people who just kill [Skyrim's] Paarthurnax and don't stop to think about it"

To test the potential of VAI, Diana and his team created an experiment using Persuasion Invasion. They went to two high schools and had 86 students play the game with half of the students playing with intervention and half playing without intervention. The results, as Diana explains, were encouraging.

"We found that when we did this kind of adaptive de-biasing intervention that, for some students at least, this seemed to improve their ability to regulate their own bias, to kind of tamp down on that kind of gut reaction to pick the argument that they think is best rather than the argument that's best for the person they're persuading, that ability for them to mitigate their own bias increased with practice. So, we were able to train this as a skill throughout the game."

Part of what makes Persuasion Invasion effective as a learning tool is that it is a video game. Aside from offering the means to scale personalized instruction, video games, especially those that are single-player, offer a safe place for players to engage with content that engages their beliefs and sense of identity.

"There's a lot of unique, interesting, challenging features associated with working in civics education that you don't get in math or biology or physics or whatever, and one of them is that students' sense of identity is bound up to the instructional content," Diana says. "So when you have a class discussion about a certain topic, students have to make themselves vulnerable because they are putting their belief out there to be responded to or criticized, and so I think that makes it very hard to do for students that don't have that sense of security."

On top of engaging with sensitive content, VAI, and the teaching methods that inspired it, actively challenges people, asking them to not just consider what they feel but question it and be open to change. That is to say, by it's nature, this sort of instruction is combative and having a sense of distance helps open people up to alternative viewpoints.

"As the player, you play a character, and already there's some emotional distance between you as a player and the character that you're playing," Diana explains. "So, when we are approaching what could be an aggressive, threatening topic, like bias -- telling someone you're exhibiting bias is a very aggressive thing to do -- if you say your character is exhibiting bias, there's a little bit of a buffer there: [the player] can grapple with these complicated issues without necessarily feeling the impacts directly on their own sense of self."

Video games are no stranger to presenting players with controversial, uncomfortable content. Series like The Witcher are famous for forcing players to make difficult decisions. But, there is a limitation to how such games can engage players. The developer can present the issue to the player but they have no way to guarantee the player will actually wrestle with the problems at hand. As, Diana says, "there are some people who just kill [Skyrim's] Paarthurnax and they don't stop to think about it." However, with VAI, players can be forced to consider the gravity of their choices and the implications of their actions.

Diana imagines if developers utilized a similar system to VAI, they could alter how players see moral choices in games. For instance the dialogue, wording, or choices themselves could be altered so players "grapple with the issues in a deeper way as [the] developers intended for them to do."

VAI, or a system akin to it, could do far more than personalize dialogue and moral choices. Diana hypothesizes that the system could even be used to actively shape narratives, having them unfold in a way determined by the player's personality -- their values -- rather than in-game choices.

"As designers, we're often trying to cultivate a certain kind of interaction," Diana says. "In my work, it's situations where players can recognize and wrestle with their own biases, but in other contexts it might be provoking a specific emotion or prompting a certain realization. In some cases, value-adaptation might be an effective tool for reaching that state.

"Imagine a game developing an understanding of the player's values (maybe throughout gameplay), and when it comes to a pivotal betrayal in the storyline, adaptively choosing the villain's action in a way that maximizes feelings of anger or disgust. Conversely, if the game wants the player to wrestle with moral ambiguity, it might choose an action that it's confident the player could sympathize with. In both cases, value-adaption lets us provide more personal and likely more powerful experiences."

Video games are on the cutting edge of interactive storytelling and have the capacity to engage audiences in a way no other art form can. VAI offers a new way of approaching that storytelling, personalizing the experience not just to entertain but to teach, showing players the inherent humanity that resides in all people as well as the limitation of their own perspective.

"If we all had a better understanding of our shared values, we might recognize those places in which our beliefs don't match our values," Diana says. "That's not going to resolve every disagreement, but it would put us in a much better place than we're at now."