Richard Bartle: "Free-to-play has a half-life"

The creator of the first virtual world predicts the decline of freemium games

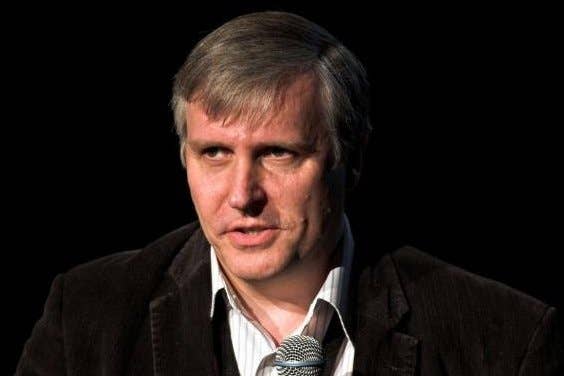

The MMO pioneer Richard Bartle has claimed that the free-to-play business model has an inevitable "half-life" that will ultimately see it fall out of favour.

In a session at the Develop conference in Brighton, Bartle staged a vigorous debate with the prominent game consultant and free-to-play advocate Nicholas Lovell. While Bartle acknowledged that free-to-play was a "great revenue model" right now, various inherent qualities would undermine its popularity.

"It will start to tail off because the people who play the games will recognise when they're about to be nickled and dimed, and stop playing them," said Bartle, who was instrumental in the creation of MUD1, the first ever virtual world.

"It will start to tail off because the people who play the games will recognise when they're about to be nickled and dimed"

"It will tail off because there is a fixed amount of people willing to spend enormous amounts of money, and there's too much competition for those people.

"It will also tail off because the type of games people want to play will change. The more games you play the more sophisticated the content of the games you will want. And when you want a more sophisticated game, then the overlay of free-to-play will be more of a problem for you. You will get a more moral sense of fair play."

A common factor to these issues, Bartle said, is that contemporary implementations of the free-to-play model are inconsistent and difficult to predict. A game may task you with collecting 18 items, for example, and only on the collection of item 17 will you learn that the final one requires either a long wait or a cash payment. In another game, the specifics of the obstacle in the way of progress will be entirely different, and each manifestation will offend a certain kind of player.

"Until we normalise, which could take a few years, and we know what's being charged for, then it'll be the wild west," he said.

In response, Lovell put his faith in the creativity of the games industry, which he believes will eventually find solutions to the problems that Bartle fears will drive players away from free-to-play games. There will still be games that allow individuals to spend huge amounts of money, but egregiously manipulative tactics will slowly be eradicated.

"My sense is that the market will keep evolving," Lovell said. "Things that initially work against players will stop working; players will vote, with their attention and with their wallets, for games that treat them more respectfully.

"Most developers want you to play their games because they're fun, not because they subject you to cheap psychological tricks"

"To my mind what free-to-play does is broaden the market by being free up front. It enables creators to keep creating. And I don't think that has a half-life because I think the games industry is endlessly innovative, and the reason why we're at the forefront of making money from digital content when every other medium is dying is because we love tech, we love change, and we love experimenting and tinkering. I'm incredibly positive."

Bartle did not share Lovell's positivity, referencing the interests of another group of people that, until then, had largely been absent from the talk: game developers, who Bartle called, "the most important people in the industry." According to Bartle, the people who actually make games simply aren't happy, "with the kind of games they're now obliged to make."

"I think that new game designers will be less keen on free-to-play as a regular model because they've seen it's disadvantages," he said in summary.

"Most people working in the games industry are there because they like making games. They want you to play them because they're fun, not because they subject you to cheap psychological tricks. They want to say things through their games. They want to make money, of course, but money is a side issue."

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)