Pick Up That Can

Human Head's Norm Nazaroff on the problems with interactive objects

Jumping back to our modern game examples, yours truly once spent several minutes trapped in a tiny room in Uncharted 2 simply because I didn't anticipate that a statue could be moved. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of statues scattered throughout Drake's adventure, and seldom are they interactive objects. I ended up resorting to the 3D equivalent of pixel hunting, in which I systematically walked around the room looking for a HUD prompt to appear and indicate what it was I needed to do.

Bringing it on home

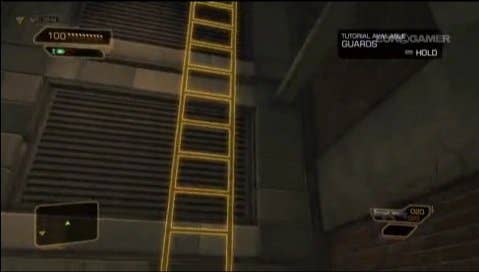

Let's get back to our original topic: Deus Ex 3's object highlighting scheme. We know that the problem it's trying to solve is real, and that similar techniques have been employed in other games. Given that, why are people so unhappy about this particular example?

The crux of the matter is this: no matter what, any attempt to break interactive objects out of the environment results in a momentary loss of immersion. Even when it takes on a much more subtle form – such as exploding barrels that are all red, or electrical switch boxes that all happen to look exactly the same – the presence of these cues reminds us that our character exists in a world of limited interactions. The result of Deus Ex's extensive, always-on highlighting is to constantly remind the player that no matter how alive and immersive the world feels, most of it isn't actually interactive.

Of course, different sorts of games require different solutions. Slower paced games (such as adventure games) have more freedom to let the player dink around and discover interactivity, whereas fast-paced games with lots of time pressure situations (such as shooters) have to be more explicit. Some settings are more restrictive than others, as well. A game set in ancient Rome doesn't have many hooks to integrate something like Deus Ex's system into the narrative, whereas a more futuristic, sci-fi setting like Crysis 2 is less restrictive. In fact, it's almost certain that Eidos was hoping to leverage the cyberpunk themes in Deus Ex to make it easier for players to accept their augmented-reality approach.

The ideal solution might be creating a world in which everything that should be interactive is interactive, but the reality is often isn't practical. It's easy enough to conceive of a game where most of the props can be picked up – just look at Half Life 2 – but what about one where all the doors open? All the vehicles can be driven? All the TVs turned on? Grand Theft Auto 4 probably comes closest, but it's not clear to me if more linear experiences would be significantly improved by these additions.

I think the most important takeaway is this: the amount of player feedback you need to give is inversely proportional to the amount of interactive objects in your game. That is, the more interactive you are the less you need to worry about getting the player's attention because you have already created the expectation that things are interactive. If you have less frequent (or less important) cases of this in your game, you need to do something to remind the player that items in the environment sometimes need to be manipulated to succeed. It could be that Deus Ex 3's scheme goes a little too far given their level of interactivity, in which case their best option is simply to scale it back until the proverbial Goldilocks is just right.

Norm Nazaroff is a game programmer and designer working on Prey 2 at Human Head Studios.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)