No Sex Please, We're Gamers

No Reply Games' Miriam Bellard on falling afoul of Steam Greenlight and the industry's longstanding aversion to sex

When Valve announced Steam Greenlight it seemed like another progressive move from one of the boldest companies in the industry. Steam's popularity had reached a point where, for the vast majority of independent PC developers, it was the only distribution platform with a large enough audience to offer a realistic chance of success. With the number of submissions growing all the time, Valve turned to the crowd: the community buys the products, so the community should be allowed to decide which products make the cut.

For No Reply Games, however, the reality of Greenlight has been somewhat different from its promise. Founded by two former employees of Guerrilla Games, Miriam Bellard and Andrejs Skuja, No Reply Games focused on perhaps the least developed part of the global market: interactive erotica. There were Japanese Hentai games, there were Flash games with rock-bottom production values, but there was nothing to compare to erotic literature, photography or film. No Reply's first project, Seduce Me, would effectively combine all three.

"We always intended to at least approach Steam with this," says Bellard, a softly spoken native of New Zealand, who has been living in Amsterdam since getting a job with Guerrilla. "I think we'd managed to convince ourselves that there was a reasonable chance that they'd take it, and the game was close enough to being finished when Greenlight came around, so we thought we'd get in at the start and see what the community said."

"It was just a very generic e-mail saying we'd violated and the game was being taken down. It struck us as Valve not wanting to deal with it, not wanting to engage"

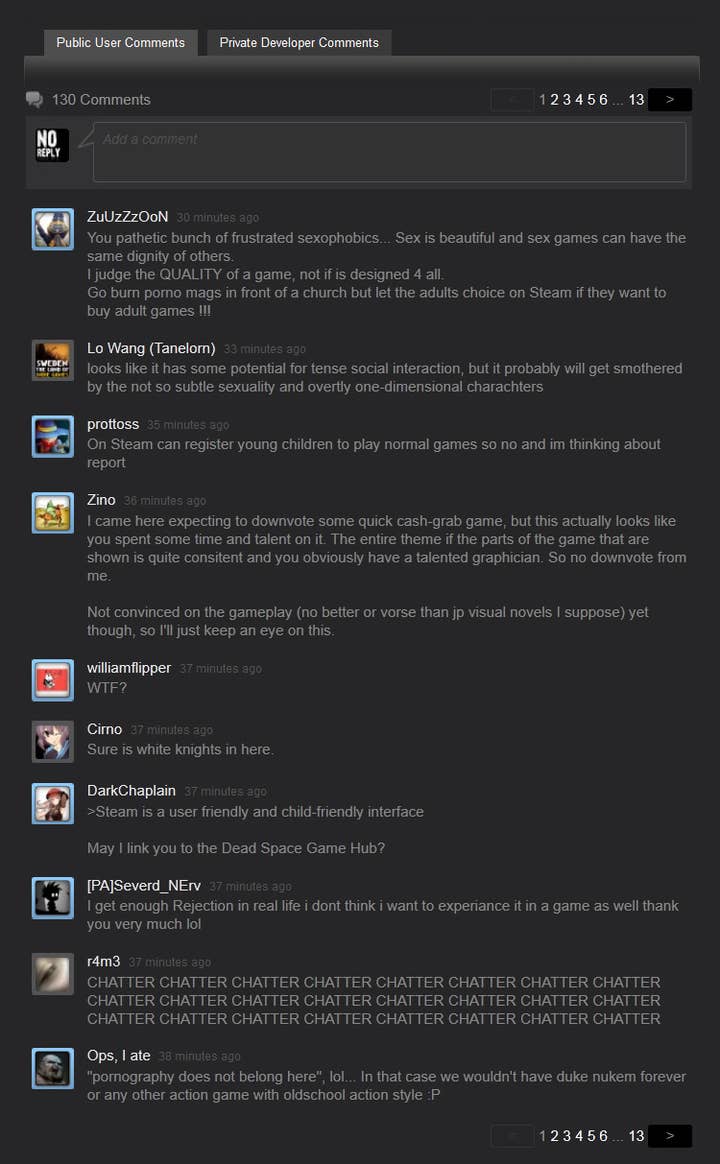

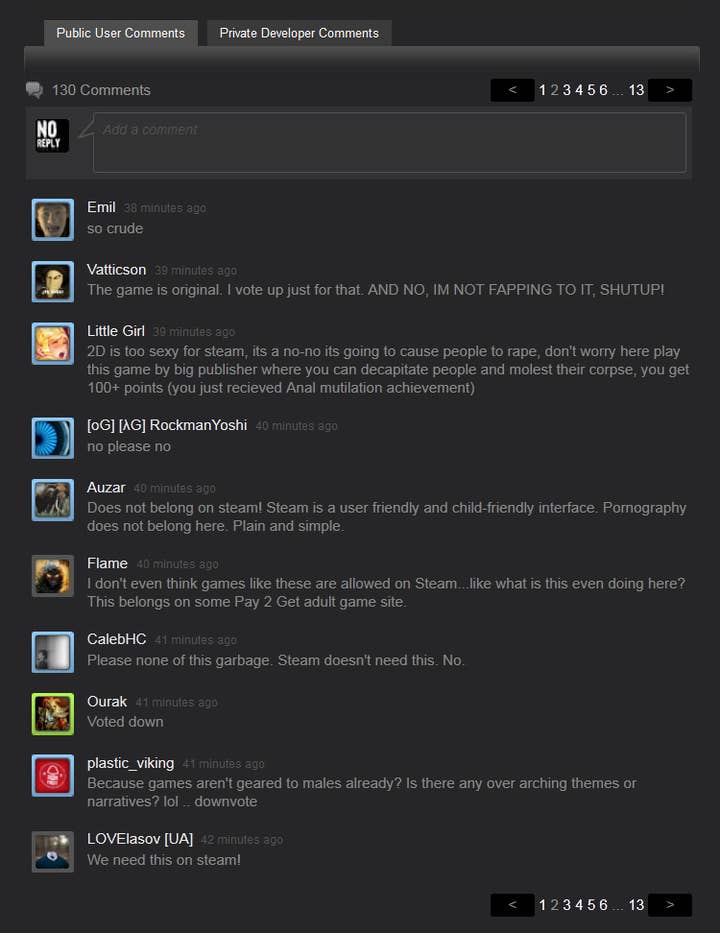

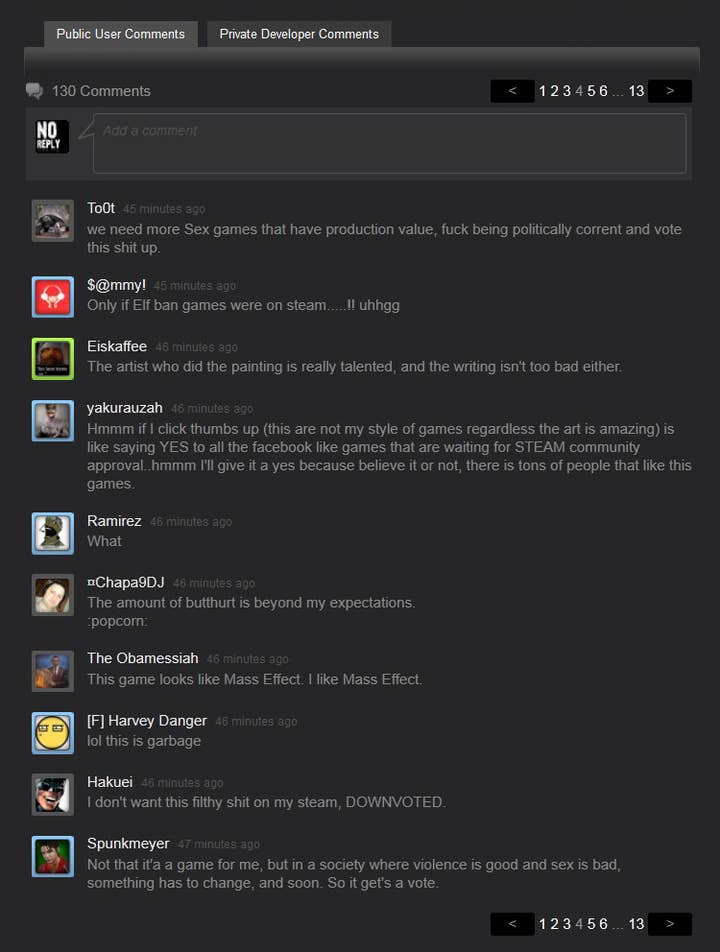

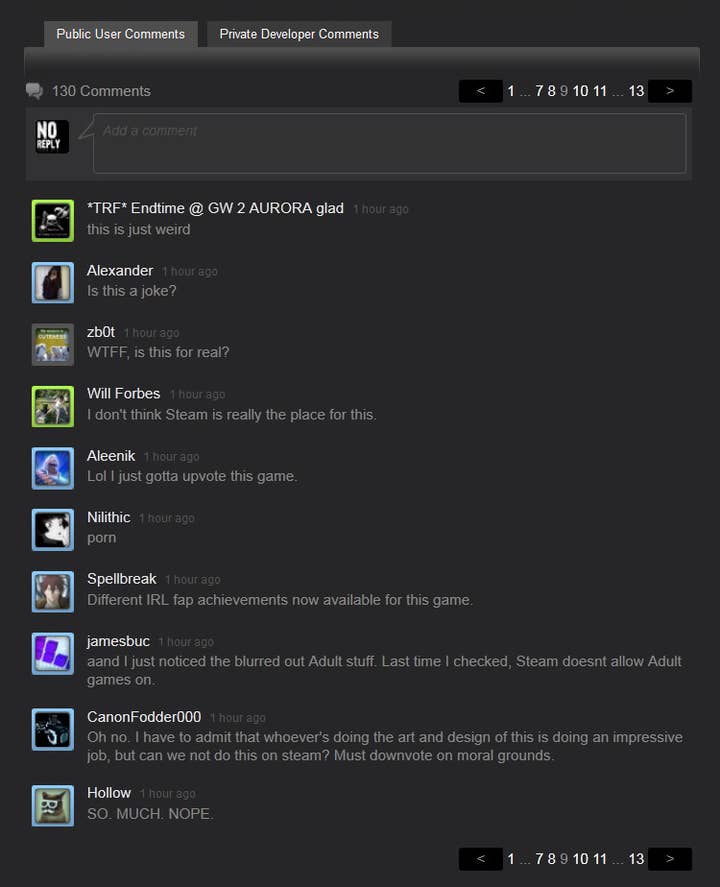

The community's response was polarised. Bellard observed a relatively even split between those calling for Seduce Me to be down-voted and threatening to complain, and those who, for various reasons, believed that content of this sort should be allowed a place on PC gaming's most pervasive distribution platform. Ultimately, the community didn't make the final decision; within an hour, No Reply received an e-mail from Valve stating that Seduce Me had violated Greenlight's terms of service and had been removed from the process.

"It was just a very generic e-mail saying we'd violated and the game was being taken down. It struck us as them not wanting to deal with it, not wanting to engage," says Bellard. "We were actually really shocked when it went down, because we thought that it would at least be allowed on Greenlight to be discussed. We wouldn't have minded taking down some of the images if they were considered too racy for the forum, but there was no communication - nothing.

"Before Greenlight happened, when indie developers didn't get [a game] onto Steam there was usually very little discussion about why not. People would sometimes not receive responses to their e-mails. Based on that behaviour, I can't see them doing any different here.

"I've heard figures from other indie developers, and proportionally Steam accounts for as much as 90 to 95 per cent of their sales. Getting on Steam for an indie developer is the difference between surviving financially or not."

For Bellard, Valve's intervention undermines the Greenlight concept. There is a good chance that Seduce Me wouldn't have received enough votes to pass muster, but the balance between the community's approval and disapproval was not the deciding factor. The Greenlight website lists two restrictions on acceptable content: "Your game must not contain offensive material or violate copyright or intellectual property rights." Seduce Me was evidently cast out for violation of the former, causing offence, but this description is far too vague to be useful to any developer wishing to push the envelope in terms of content.

If it can be said that greater diversity in gaming is important for the future of the medium, and it can be said that what offends one person won't necessarily offend another, then Valve's decision to remove the game is effectively a political act. How many people need to be offended for a game to be removed? Should the moral compass of certain individuals dictate what content is offered to those with a different view? For Bellard, the side of the argument that Valve chose to take will only convince other developers to err on the side of caution, and create content that won't transgress a frankly vast possible spectrum of opinion.

"Getting on Steam for an indie developer is the difference between surviving financially or not"

Of course, these strictures on what is deemed fit for sale aren't difficult to find in the games industry. Apple's guidelines for iOS submissions have attracted criticism for prohibiting a wide range of themes and subject matter, from sex and sexuality to depictions of animal faeces, but Bellard associates Valve with a different set of values.

"I understand it more on iOS, because Apple has this air of, 'we're here to protect you, everything just works and it's a nice, safe place to be'," she says. "That's Apple's whole ethos: I don't like it, but I understand it. I don't understand Valve's, because it's supposed to be part of the PC, Linux ethos. I'd always seen them as being on the side of the underdog, on the side of free speech."

When considering this issue, it's important to remember Steam's global reach. Valve sells games to a range of different countries, each with its own standards when it comes to sex and violence: Germany, for example, is more tolerant of sex than violence in cinema, television, gaming and other forms of entertainment; in America that bias is reversed. On the face of it, there's no practical reason why these varying standards should lead to games with sexual content being excluded - it certainly doesn't when it comes to violence - but Valve's decision to remove Seduce Me could simply be an example of playing it safe in a global marketplace.

"I personally don't think Valve needs [to play it safe]," Bellard responds. "I think Valve is in a position where they could push this if they wanted to. Sure, they might lose a very small amount of their audience, but they would gain others... Why they've chosen not to is possibly that they're part of that American culture, and they view this issue with that American point-of-view."

"I personally don't think Valve needs to play it safe. I think Valve is in a position where they could push this if they wanted to"

To a large extent, the righteousness of Bellard's position is besides the point: Steam is Valve's platform, just as iOS is Apple's, and it's entitled to make decisions about the propriety of different subject matter, even if that basically places that content in a commercial and creative ghetto. Frankly, the deeply conservative response of the Greenlight community is even more provocative.

Bellard and Skuja aren't pornographers; they are independent game developers attempting to fill a gap in the market that has existed since the dawn of the industry. On one level it's just good business sense, and yet Seduce Me, which is scarcely more hardcore than 50 Shades of Grey or The Joy of Sex, provoked vitriolic opposition. The complaints went beyond simple disapproval, or the refusal to purchase a product that isn't to your taste. Many comments were nothing less than blanket condemnations of all sexual content, and Bellard believes this is indicative of the way even the most engaged gamers view their hobby.

"The people we've spoken to [about the game] here in Amsetrdam, we just never hit that intensity of disagreement. Many of them felt that it wasn't for them, but there wasn't that sense of outrage that we saw from the Greenlight forum," she says.

"There's still that historical view of games being for children, and even though the average gamer is now 30 yeas old it's still the gut reaction. With books, you have children's books, teen fiction, adult books of all genres. But we tend to view games as one solid category. I think things like this can just be about habit; it's just what we're used to."

This is an important point. Despite the ubiquity of extreme violence - a talking point following this year's E3 press conferences - the games industry has a somewhat hysterical track record when it comes to sex. The most famous example is the Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas mod, Hot Coffee: a mini-game depicting consensual sex between adults that somehow managed to be more controversial than the killing sprees allowed by the game's mechanics.

"There's still that historical view of games being for children, and even though the average gamer is now 30 yeas old it's still the gut reaction"

With this in mind, it's pertinent to consider how violent a game would have to be to raise a similar level of ire from the Greenlight community, and which side Valve might take in that situation. Similarly, would a product as explicit as Seduce Me have been greeted by the same condemnation if it were on a Greenlight-esque service for film or literature? In a world where Netflix can host Disney fare and art films with scenes of penetrative sex without complaint, it's certainly hard to imagine.

For Bellard, this is just another teething problem for an industry that is perhaps less mature than those who work within it would believe. The acceptance of sexual imagery and themes has been the source of enormous struggle for every entertainment form, but it was also a vital aspect of their evolution and cultural acceptance. For now, though, there is little encouragement from either the industry or the audience for developers to demolish those taboos.

"That there's no content like this is exacerbated by the fact that there's nowhere for it to be sold.," Bellard says. "Once content starts to appear places will be found for it to live, which will encourage other people to make that kind of content.

"The indie scene is quite young, and I see where we are with games as like where the film industry was in its early years, when it was dominated by the really big studios, before developments in technology allowed people to break away from their control. That's where games are at the moment. We've finally got products like Unity, which allow you to make a game for a lot less money, and allow you to break away from the control of the big companies. And big companies are always more conservative."