Tech Focus: Game Graphics vs. Movies

Does resolution really matter? Developers discuss bringing a filmic look to next-gen titles

The ambition of what is being suggested here shouldn't be understated. It would involve a lot of buy-in not just from the game-makers, but also from the audience themselves who have become conditioned to a particular aesthetic. The perception of video games graphics in the HD era is that there's a purity to the look, a certain pristine edge to the visuals that has only been challenged by a very small number of releases (Limbo and Killzone 2 are two examples that spring to mind).

Even in some existing console titles, there's already evidence that the focus on detail is not so important and that rendering resources can be better deployed elsewhere

To truly work it would also need to be accompanied by technologies that make the most of the "freed up" processing budget. Lighting technologies in particular would need to make a step-up, but other elements such as animation and direction would also need to match. To get the filmic aesthetic, it's as much about how a game moves as well as how it looks.

However, in terms of the quality vs quantity argument, there is already a range of evidence within the existing console generation that the focus on detail is not so important and that rendering resources can be better deployed elsewhere. Call of Duty is perhaps the most spectacular example, if not quite along the lines being suggested by Timothy Lottes. It's a fact that the biggest example of the triple-A philosophy does not render at a recognised high definition resolution: a typical 720p game offers an additional 50 per cent of resolution over the 1024x600 framebuffer utilised in Modern Warfare 3 with the developers using the resources available to operate at a target 60 frames per second.

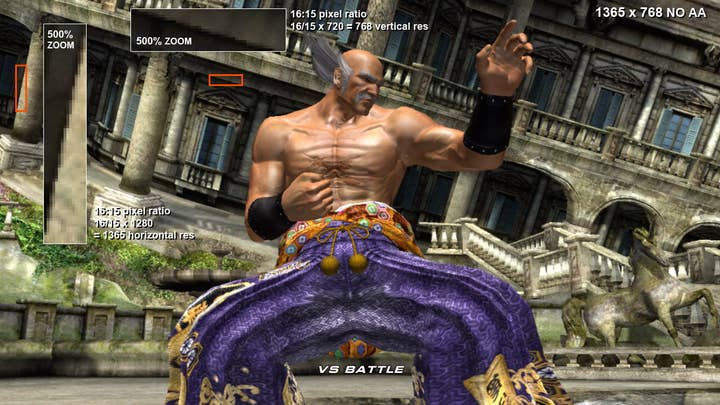

Other examples do tie in more closely with the ethos being suggested by Lottes: that it's not the pixel count that's important to image quality rather than the way those pixels are used. Namco Bandai's Japanese teams have experimented a great deal with resolution on current generation systems, most notably in Tekken 6. Without motion blur active, the Xbox 360 version renders natively at 1365x768, downscaling to 720p - using super-sampling to give some anti-aliasing. However - perhaps surprisingly - with motion blur active, resolution drops to 1024x576, but the game measurably looks better. Not only does the blur add more realism to the movement, but more detail appears to be resolved in the textures even though base resolution is effectively halved.

Discussing Tekken 6 in particular, RedLynx's Sebastian Aaltonen - the main technical mind behind the brilliant Trials HD - discusses how the lower resolution mode offers up system resources for other forms of graphical processing:

"Both configurations fit well inside the 10MB eDRAM. The 1024x576 is kind of a strange choice, as it's only around half the pixels of the 1365x768 and the cost of the blur filter comes nowhere close to the performance gained from the resolution decrease, and they are not eDRAM limited either," Aaltonen observes.

"The resolution reduction itself is not something I consider strange, but a reduction this large means they have something else going on than just the motion blur. The better texture detail you are seeing could mean they have enabled anisotropic filtering for the lower resolution."

What Timothy Lottes is suggesting is something a whole lot more ambitious - a new approach to rendering from the ground upwards, encompassing both the engine and the creation of the core art assets.

A more dramatic current generation example would be Remedy's Alan Wake. The game actually operates with an even bigger resolution penalty than Tekken 6, with a native 960x544 framebuffer - but the combination of 4x MSAA, phenomenal lighting effects and post-processing work ensures that the game does not suffer for it: aliasing and the dreaded "jaggies" are not especially an issue (though screen-tear definitely is). Remedy itself says that Timothy Lottes' FXAA is utilised in the American Nightmare Xbox Live Arcade sequel, most likely in place of the 4x MSAA of the original - so it will be interesting to see if resolution is increased, or if the processing resources are instead used on cleaning up the intrusive lack of v-sync.

As game developers transition across to a new breed of architecture, exciting possibilities open up - the ability to present gameplay in ways we've never seen before. There's been a lot of discussion about how to make the next-gen matter - this is just one discussion, one possibility. Developers like Crytek have already indicated in their SIGGRAPH and GDC presentations that the ability to innovate with new rendering paradigms is limited on current generation platforms. New hardware means new opportunities, and the notion of key developers, artists and decision makers already discussing the possibilities freely and publicly is another credit to the openness and the collaborative spirit that flows through the video game industry.