OnLive: Assessing the UK Launch

Digital Foundry analyses OnLive - is this really the future of video games?

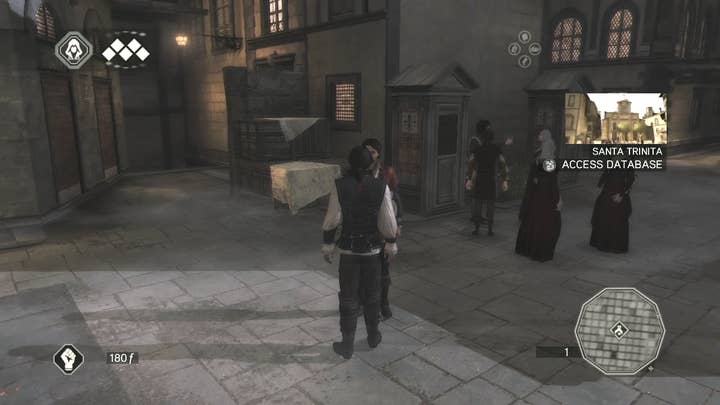

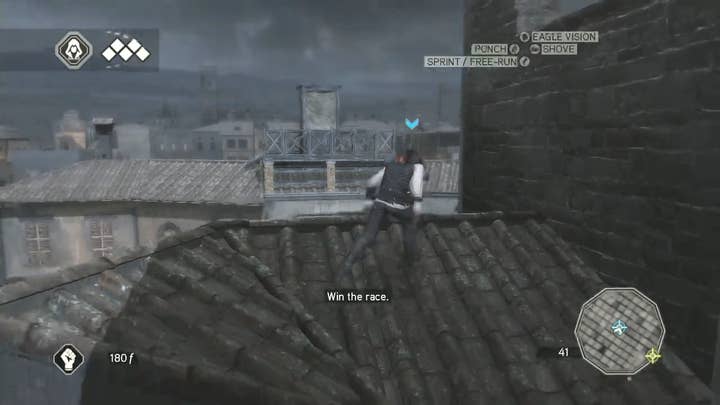

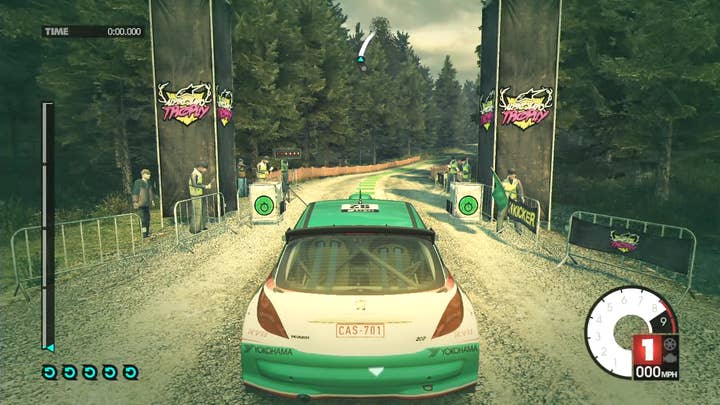

Image quality is equally variable. In motion, there is almost always a detail-killing blur, which scales up to full-on macroblock artifacting depending on the amount of movement on-screen and the colour schemes employed. Batman: Arkham Asylum favours the encoding scheme and looks good by the standards of the service, LEGO Batman generally looks fine in-game but looks poor on the cut-scenes, while in-game action on Warhammer: 40,000: Space Marine is mired in artifacts and it's difficult to describe it as any kind of high definition experience.

At the end of the day, OnLive is what it is: a lo-fi alternative to console gaming, offering significantly impacted visuals and often muggy response from the controls. There are types of game that will work fine with it, there are others which really don't suit the system - whether it's down to lag or visual complexity being lost in the video encoding process, or both, the result can be disappointing if you're used to traditional games consoles. When it works well, there's an almost magical edge to it, but when gameplay is compromised owing to technology, it's an immensely frustrating experience.

So will OnLive find a significant audience? Firstly, while the price of games is generally too high by whichever yardstick you care to measure it against (console retail games, Steam etc), I do think that the £6.99 PlayPack has much to offer - it'll be interesting to see how well the platform holder can manage to keep it stocked with decent games. By addressing gaming as a subscription service in the same way that people sign up with Sky, or for their broadband, OnLive has made a canny move. The price is right too, and subscribers get 30 per cent off the price of full purchases, which helps to address the price-competitiveness problem a little.

There are types of game that will work fine with OnLive, there are others which really don't suit the system - whether it's down to lag or visual complexity being lost in the video encoding process

I also think that while picture quality can be really rough, pitched at the right audience, gamers probably won't care on all but the most extreme cases. This is the generation that has grown up with YouTube quality, that watches TV on Sky or Freeview where picture quality (HD channels apart) is generally rather low. Core gamers though definitely be able to tell the difference, and I suspect that only a big boost in bandwidth will get this encoder up to scratch.

In terms of the overall package, while I can see a great many game designers (not to mention artists) upset at how OnLive compromises the quality of their work, the fact is that the service functions and it is playable. Control might not feel 100 per cent "right", but in the absence of a "correct" reference, it's playable enough to feel authentic.

Where the company needs to improve is in terms of the robustness of the platform. If it doesn't work properly on all broadband providers, there's a big issue that desperately needs to be resolved. I also found that the quality and consistency of service took a nosedive if WiFi is utilised, even if I was right on top of the router. Unfortunately for OnLive, if it's going to pitch for a casual audience, it really needs to have both of these issues licked.

It's also clear that game publishers need to step up to the plate too in making the overall offering more attractive. Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Tropico 4 and Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine are the only stand-out titles that are recent. The rest of the launch line-up comes across very much like a dumping ground for games that have enjoyed their sales spikes on other platforms. The mentality here is puzzling: at the very least OnLive is a superb means by which to sample games that may actually end up being bought on other platforms, but in some cases it almost looks as if publishers want to sabotage the whole sampling concept.

A good example of this is Deus Ex: Human Revolution, where the system offers no rental or demo options, just a price-point that is actually more expensive than it is on competing digital platforms. It's ultimately self-defeating and also serves to make OnLive's offering look inconsistent. I cannot help but think that it is not the fault of the platform holder: there's certainly no technical reason behind it and the only reasonably explanation is publisher intervention. The bottom line is that either publishers support the new platform and all of its features, or they don't. Half-in or half-out doesn't really cut it.

Another example is Electronic Arts: there's no Battlefield or Need for Speed heading to OnLive: instead, the best game it offers is Bulletstorm (coming soon, unfortunately we couldn't test it). It's a fine title, but probably not one ideally suited to the limitations of the platform. EA does seem to have embraced the Cloud concept with its recent Gaikai deal, which suggests that EA prefers to invest into the Cloud as a means of providing a demo - a sampler designed to get people out to the shops and buying boxed product. Certainly, in this case, it's very easy to forgive the foibles of the set-up and nobody can deny that Cloud gaming is a superb mechanism for supplying almost instant game content. But as a gaming platform charging full sticker price? Whether it's down to limitations of the system itself or in the surrounding infrastructure, perhaps the kindest way to put it is that OnLive is years ahead of its time.