How the Rainbow Billy team swapped combat for conversations

ManaVoid discusses the process of overhauling its indie RPG to make it a non-violent game about empathy

From the screenshots, Rainbow Billy: The Curse of The Leviathan may look like a simple turn-based RPG (albeit one with a colourful art style and an indie vibe). And, to be fair, that's how it was originally supposed to be.

The game was dreamed up by ManaVoid Entertainment CEO Christopher Chancey and art director Anthony Vaucheret shortly after they met in 2018. Vaucheret, a big fan of how Disney-style animation was making its way into games via titles like Cuphead and Bendy and the Ink Machine, wanted to create an animated black-and-white RPG, but Chancey was keen for there to be more colour.

Eventually, the two decided on a game where the world starts out as black-and-white and your objective is to explore and find ways to bring back colour. The game would have a traditional turn-based RPG combat system similar to Final Fantasy or Pokémon, and the 1,720 backers who pledged CA$ 88,480 ($68,955) to ManaVoid's Kickstarter campaign suggested the audience would be okay with that.

Then the team read a GamesIndustry.biz analysis into the balance between violent and non-violent games at E3 2019.

"Your article came at an opportune time for us because we were having issues with our combat system at the time," Chancey tells us. "I always thought it was really weird in Pokémon how you're basically trapping creatures and having them fight each other, kind of like a dog fight type situation, and everyone's cool with this.

"Your article came out, and I'm like, 'Okay, well, you know what? It sucks that there are not enough games that just shun violence altogether.' Video games as a medium are still exploring a lot of things. We've pigeonholed ourselves pretty quickly in certain genres that just keep repeating the same loop, and so I wanted to break that. And we decided to go the whole non-violent route."

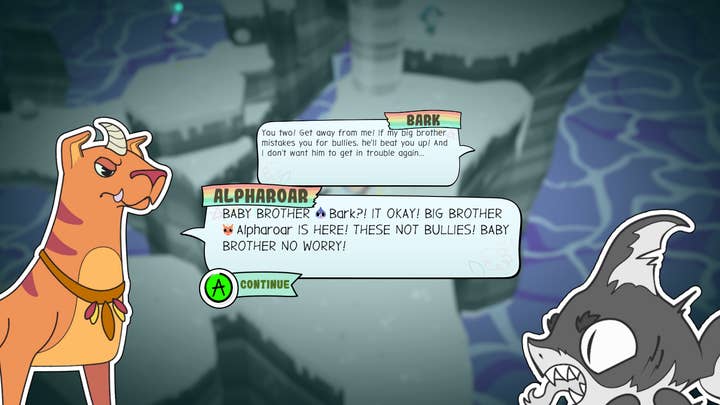

Changing the combat changed the context of the entire game; it becomes focused on empathy rather than conflict. Instead of battles, you now enter confrontations, but while that may still sound aggressive, the objective is to talk to the opposing creature, choosing from dialogue options in the hopes that their response helps you better understand their issues. Doing so successfully reveals the colours they lack, which you can call on the monsters in your party to deliver. The system is still turn-based, but the goal is now to fill the enemy's icons with colour rather than to whittle down their health bar. Victory changes the creature's outlook on life, restores their full colours, and adds another friend to your party.

An added differentiator is the use of minigames and quicktime events throughout the battle to improve your defense or power up your empathetic endeavours.

"One of the things that I hate about old-school RPGs is that you select what you want to do and then you wait for a minute while the animation passes," Chancey explains. "We wanted to keep people engaged even while their choice was done, so we added on the QTE phase and that keeps people still in the flow of the game. This is particularly important with the redesign that we did because when there's more dialogue in a confrontation, then there are more stops and starts."

"I always thought it was really weird in Pokémon how you're basically trapping creatures and having them fight each other, kind of like a dog fight type situation, and everyone's cool with this"

Overhauling the combat system involved going right back to the code and changing how interactions worked. Mechanically, players are still selecting options and watching things play out, but choosing dialogue rather than an attack or spell involves more thought on the player's part. The UI also needed a revamp in order to house entire lines of dialogue as opposed to short text indicating your battle options.

The broader flow of these encounters also changed. With more traditional RPGs, you often encounter identical copies of the same monsters, allowing you to learn their weaknesses and over time develop a strategy to defeat them faster. When a variation of that monster arrives, you understand the combat system well enough to take it down.

"We couldn't really do this here because there was no more damage, there was no more HP," says Chancey. "So pacing the difficulty level became more about how many colours you needed to discover on the character, and the strategy about which colours to use and when."

There are over 60 characters in the game for players to encounter, and Chancey was keen for each one to feel unique. Traditional RPG mechanics made this difficult, so the uniqueness came from each monster's backstory. Lore was developed around every confrontation, and the writing became a much more important part of the process than the team initially envisaged.

"To keep the encounters unique, we had to really think outside the box on how we wanted things to go back and forth," Chancey adds. "Usually you'll have character A talk, and then character B respond, and then character A talks again. We designed a system that allowed us to not only have ABABAB, but we could have a third character come in. We could have dynamic text, so because we wanted the dialogue system to feel engaging as well, we could colour text, we could animate text, we could highlight certain things. That also came about after we decided to do the confrontation system."

The writing also presented a delicate balance to strike. Now that confrontations were built around sensitive issues like depression, the aggression from the dialogue had to be removed.

"Billy's not like, 'I'm going to recolour you!'," Chancey says. "It's more like the whole design of it is empathy, so we wanted people to understand what communication is like and what a conversation looks like in 2021. I think it's important to remind ourselves sometimes that having opposing points of view is okay."

At the beginning of a confrontation, players have the option to talk or listen. Listening helps them understand more about the other character's ordeal, while talking enables you to try to reach out to them and help them, in part by trying to pass on their missing colours. It's an example of how a simple change in words can recontexualise an entire experience.

"It's not 'Attack', 'Defend'. It's 'Talk', 'Listen', and that immediately changes the dynamic entering the confrontation," Chancey says. "Instead of calling it HP, Billy has a morale bar -- and that's important, too. HP is directly linked to your health, your corporeal, general wellbeing. When you're taking away HP, you're hurting that person. All of these little changes really made it easy to take away from the whole violent part of the traditional RPG combat system. It's essentially the same dynamics and mechanics, actually. It's just the rewording of it that makes it suddenly not violent.

"You would think that to create drama or interest, you need to have a fight... But if you use the right words, [you can] make your game as non-violent as possible"

"It switches the perspective a lot. There's a lot to say about the power of words. Saying the right thing to the right person at the right time can change a life."

There's a sensitivity, too, when dealing with personal issues. ManaVoid were keen to avoid presenting Billy as this child psychologist that magically makes things all better. Chancey recognises there are many ways to deal with any issue; instead, the emphasis here is on "empowering the person to keep communicating, or keep empowering the person to go and feel what they need to feel along the way."

ManaVoid, thanks largely to its publisher Skybound Games, worked with a lot of consultants on this project. They partnered with Rise Above the Disorder, which helps gamers with mental health issues, who vetted every line of text in the game. Another consultant specialised in trans children ensured the non-binary Billy was relatable. Skybound even brought in a consultant, John Morgan, who has worked with children's literature and comic books, to ensure everything was appropriate and understandable for a younger audience.

After overhauling the game and removing, or at least recontextualising the combat, ManaVoid found Rainbow Billy received an even stronger reception when showcasing at events like PAX -- especially among children and their parents. The studio began leaning heavily into the non-violence as a pillar of the game's marketing.

"We wanted to position ourselves also as a non-violent video game, because not enough non-violent video games exist in our opinion," said Chancey. "Your article obviously highlighted that at the time, but just in general, people felt that there were enough gunplay shooters with white males doing things, and we wanted to just do something else."

Chancey also encourages other developers to reconsider alternatives to combat, if only in the presentation. As much as it took a lot of work for the Rainbow Billy team, the indie's CEO is confident it was worth it.

"You would think that being able to create drama or create interest in a project, you need to have a fight. And I think even in our game, we call them confrontations, but in the end, you're interacting with a person who has an adverse, maybe, point of view, so I think you'll always have the good guy, bad guy, kind of situation.

"But I think if you contextualise it the right way, you use the right words, and you fundamentally understand how a child might be able to see a confrontation, or how a child should learn how to confront, be it their emotions or a bully or whatever, and I think then you'll be able to understand what you need to do to make your game as non-violent as possible.

"I don't want to speak for anyone else. It was our process, our journey, that brought us here, but I just think oftentimes, we're afraid that the game is not going to sell, or we're afraid that we won't do it justice, or that we don't know how to do things, and I think just letting go of that fear and owning up to what you want to do is the way to go. And we're really, really happy with the change that we made. This game is the complete vision that we were trying to accomplish."