Where is the line between fan creativity and IP infringement?

Harbottle & Lewis' Kostya Lobov discusses the balance rights holders must strike when protecting their property and allowing fans to express themselves

Takedown notices have scuppered many a fan-driven project in the realm of video games, and yet some creators still seem to be confused as to what they can and can't produce as we still see works facing the threat of legal action from time to time.

In some instances, it's fairly obvious why; for example, it was unlikely an Unreal Engine 4-remake of Goldeneye 64 was ever going to be allowed to see the light of day, even if distributed for free.

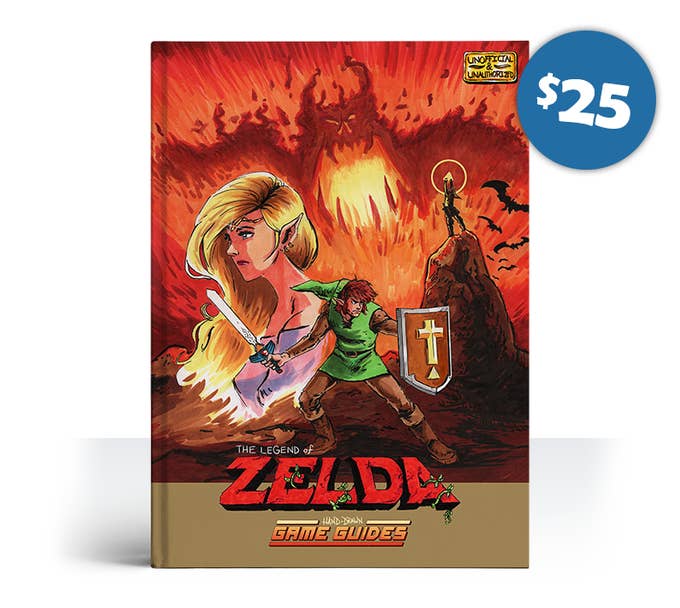

But earlier this month, a Kickstarter-funded series of game guides for classic NES-era titles by Nintendo, Konami and Koei Tecmo was shut down. The creator, Phillip Summers, didn't go into detail, but did mention wanting to avoid "legal trouble."

The guides contained walkthroughs and tips on titles like The Legend of Zelda, Metroid, Contra and Ninja Gaiden -- information that can be found on many an online guides section or YouTube channel -- illustrated by maps and pictures hand-drawn by Summers.

It's unknown which company issued the legal warning or which elements of the guide triggered it, but Kostyantyn Lobob, partner at UK law firm Harbottle & Lewis, suggests that the artwork is likely the reason for the project's downfall.

"We can't speculate on the specifics of this case, but generally speaking it's unlikely that a complaint would centre on the text content of a guide itself -- assuming that content is original, and is not proliferating cheats or exploits, which could be problematic for other reasons," he says.

"It's more likely that a complaint would focus on either the use of artwork, use of trademarks in the product or in the course of marketing it, and/or the creation of a misleading impression that the product is licensed, authorised or endorsed by the company."

That perhaps makes sense. The covers for the Hand-Drawn Game Guides each bore Summers' own illustrations of the main characters, including familiar faces like Link and Samus Aran, which are almost certainly protected by their respective IP holders. But surely this can be considered fan art? Summers has not produced exact copies of images produced by Nintendo, for example, but created his own scenes using his depictions of the characters. Companies like Nintendo have been creating iconic characters for decades, ones that millions of people around the world have embraced -- are those people not entitled to celebrate or express that love in their own style?

"It's important not to fall into the trap of thinking that, just because everyone else seems to get away with it, it's fine for you to do it too"

"This is a fair point, and companies are not blind to this," Lobov admits. "Most of them don't want to alienate genuine fans, and a lot of them are supportive of what they do.

"However, the problem is that often, mixed in among the genuine expressions of fandom, there are bad actors who are simply looking to make money by trading of someone else's IP rights, and they could be damaging the brand and the community as a whole in the process. Letting this go unchecked can have disastrous consequences for the IP owner, as their brand could eventually become swamped and virtually enforceable.

"The good and bad actors all use the same platforms, so how do you, as an IP owner, separate them? The answer is that every company will decide its own criteria for where it draws the line on enforcement, depending on a variety of commercial factors. For example, an indie studio releasing its first game might not be as concerned about unofficial fan-made products being sold online as a global publisher releasing the third instalment of its AAA franchise, which already has an extensive merchandise operation."

Where, then, is the line between fan expression and an unlawful product? Again, direct copies of games is an understandable faux pas on the creator's part, but the shutdown of Hand Drawn Game Guides muddies things somewhat.

"It's worth emphasising that 'what is unlawful' and 'what will receive a takedown notice' are often two different things," Lobov explains. "At any given time, there could be literally thousands of items or pieces of content out there which are technically infringing, but a large proportion of them might never be complained about.

"Reasons for this vary from company to company, but typically it's because resources for enforcement are finite and it's difficult to police all of the internet in real time, so there needs to be some prioritisation. And in some cases letting a minor infringement slide is, overall, a better commercial decision for a brand. Again, approaches to this vary drastically between companies, with some having a near-zero tolerance policy.

"It's important not to fall into the trap of thinking that, just because everyone else is doing something and seemingly getting away with it, it's fine for you to do it too. The fact is: you simply don't know why those products have not been taken down. Maybe they have a licence. Maybe they will get taken down next week. Maybe they've ignored a letter of complaint and are about to get sued. The reality is that anytime you use somebody else's IP rights -- without getting permission -- there is some degree of risk that it could result in a complaint."

Part of the problem, Lobov adds, is the rules are complicated with a "degree of fuzziness" rather than a clear line between right and wrong -- something that makes it harder for non-lawyers to navigate. But at its most basic level, he says that copying the whole or a substantial part of a copyrighted work -- whether that's a logo, a character image or a screenshot -- will infringe copyright.

The only way to avoid infringement -- other than getting the rights holder's permission, of course, is to prove your product or works fall under 'fair dealing' in the UK, 'fair use' in the US, or whatever similar exceptions may be available in your country.

"This is a whole area of law in itself and difficult to summarise in a few sentences, but it's safe to say that these exceptions are not as wide as some people think, and relying on them becomes more difficult if you are selling a product commercially and at scale - such as unofficial fan-made merchandise," he says.

And that's just with regards to copyright. Fan creators also need to take into account trademarks, which are entirely separate and have no 'fair dealing' defence. These can be used on names and titles, logos, slogans, and any distinctive elements of a game, including its characters. There are other IP rights protections that games companies may use, with Lobov summarising that most of what players can see when they're playing the game is likely to be protected by copyright.

Going back to the fan art argument, does the amount of original work produced -- regardless of whether its basis is protected -- have any impact on whether a project is likely to be shut down? Lobov says it can vary from case to case.

"It's probably fair to say that, for a lot of IP owners, products which have a high amount of inherent originality or are highly transformative are going to be less of a priority for takedowns or complaints than blatant copies," he says. "Other aggravating factors, which make a complaint more likely, include products which are dangerous to consumers or don't meet regulatory requirements; products which are incompatible with the company's values or target audience (e.g. smoking paraphernalia branded with IP from a game popular with children); products of poor quality; and/or products being sold commercially in large quantities.

"These are not hard and fast rules - different companies will have different attitudes to this. As I mentioned, some companies have a near zero-tolerance policy, and will (eventually) take down almost everything which they are legally entitled to. For those companies, if something is still up, it probably just means they have not got to it yet."

Monetisation is also likely to have an impact. Hand-Drawn Game Guides raised $320,000 on Kickstarter, for example. Again, while this was not cited as a specific reason for the takedown, Lobov does observe that commercial sales are likely to feature higher on a company's radar when it comes to infringement.

"But, again, this doesn't mean that non-commercial uses are safe to do," he says. "The bottom line is -- if you create something that is not entirely original and uses third party IP rights -- without that party's permission -- you need to accept that there is a degree of risk in what you are doing."