GI 100 | Game Changers -- Part Four

Game Changers continues with Saudi Arabia's first women-only game event, building an industry in Singapore and Malaysia, and galvanising the Japanese indie scene

As 2020 draws to a close, many will reflect on 12 months defined by stress, upheaval, and the urgent need to confront some difficult truths about the way the games industry operates, and the myriad ways it can be a better and more inclusive place.

But just as that process of self-examination is necessary, so too is recognition for those already working to solve those problems. In this GI 100 series we will profile 100 individuals and organisations making progress in vital areas like diversity, accessibility, charity, mental health, progressive politics, lifting emerging markets, uniting communities, and more -- people whose stories can show us how this industry can be that better and more inclusive place.

Below is the fourth group of ten Game Changers, with ten more to follow every working day until December 18. The project is sponsored by Unreal Engine -- you can read more about it, and find links to all ten parts, here.

Ghada Almoqbel, GCON

Diversity is a huge issue, and it's easy to overlook the unique barriers people face in different parts of the world.

GCON, the women-only game event in Saudi Arabia, is a case in point. According to its current owner and CEO, Ghada Almoqbel, it was started when women were banned from another gaming convention. Hosting a "mixed gender event" in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia at that time required compliance with more regulations, the completion of more paperwork -- the organisers didn't believe there were enough female gamers to make the extra effort worthwhile.

Tasneem Salim, Felwa al-Swailem and Najla Al-Ariefy took the initiative, and hosted the first GCON in 2012. Those early shows attracted more than 4,000 attendees.

"At first it was just a gaming convention for women, then almost immediately it started to become more than that by organising the first game jam that focused on empowering female game developers in the Kingdom," Almoqbel says. "GCON since then had its value and reputation in the women gamers and game developers community."

Almoqbel represents the second generation of GCON, having taken over running the organisation from its original founders in 2018. It was an organic transition; Almoqbel vividly recalls attending her first GCON in 2013 at the age of 17, with "the only girls I knew that played video games," her sister and cousin.

"I was amazed, an unforgettable experience," she recalls. "A huge pretty place, filled with many video games including AAA and indie games. Many tournaments and competitions. And most importantly, 4,000 women and girls of all ages -- teenagers to adults and moms -- who loved gaming as much as I do, and maybe more.

"I knew instantly I wanted to be part of the team who enabled all this. And I wanted to do more. I didn't know what exactly at the time but I was game for whatever comes next."

Almoqbel joined GCON as a writer for its website in 2014, and she is now CEO of the entire organisation. The conversation around diversity in Saudi Arabia changed with the introduction of the government's Saudi Vision 2030 strategy in 2016, she says, and there is now a more widespread push to empower women across multiple sectors. Almoqbel's early actions as GCON's new leader were defined by that shifting context.

"I knew instantly I wanted to be part of the team who enabled all this. And I wanted to do more"

Ghada Almoqbel

"Keywords of our new vision [are] 'inclusiveness' and 'women empowerment'," she adds. "We aim to enable inclusiveness in the community and industry, as well as supporting and empowering women."

In addition to GCON's original founders, Almoqbel is most grateful to her family, whose encouragement and support has never wavered as she pursued her goals. More broadly, she calls upon the industry to match its words of support for diversity with action.

"So many say they support women in the industry, but only a few actually genuinely care to understand our actual needs and wants," she concludes. "Genuine understanding and opportunities is all we ask for."

Meagan Byrne, Achimostawinan Games

Byrne quips that her route into gaming is a bit of a "weird story," because she didn't have a typical entry point of simply being passionate about the craft. Instead, she came from a background in lighting design, but was forced to make a change during the 2009 recession.

"After about the fifth or seventh short-term contract I was like 'Okay, this isn't working. What does the Canadian economic forecast say?' -- because I like data before I make major life decisions," Byrne says. "And right at the top of the 2012 forecast was Software Development and Video Games. So I took the plunge."

Since then, Byrne has worked as the lead digital and interactive coordinator at imagineNATIVE, an organization that promotes and presents Indigenous screen content. Out of that role, she developed Night of the Indigenous Devs as a riff on Day of the Devs, aiming to draw attention to Indigenous-made video games.

Currently, she's a narrative mechanics designer and owner of Achimostawinan Games, an Indigenous indie games studio that makes games with original Indigenous stories. She has also been on the board for both the non-profit gaming arts organization Dames Making Games and Indigenous new and digital media artist collective Indigenous Routes.

"Creating the space that I wish I had starting out in video games was really important to me," she says of these roles.

Byrne is grateful to people like Archer Pechawis, who brought her into Indigenous Routes, and Elizabeth LaPensée, who has been her mentor since her early career. She also has found support from Dames Making Games, the Indigenous game development community, and programs like the Toronto Arts Council, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts that have given her safety nets with which to create the games she wants to create.

"The industry needs to start acknowledging that it is almost entirely made up of those in the middle-class or higher"

Meagan Byrne

"The industry needs to start acknowledging that it is almost entirely made up of those who are in the middle-class or higher," Byrne says. "So often funders and publishers ask for a level of polish on demos and prototypes that is only possible if the team does not need to work other jobs, or if everyone is doing free labour, or barring that, that team members are sacrificing their wellbeing and health to hit the level of polish required while living in poverty or working other jobs. Too often I see funds aimed at bringing equality to the industry that continue to privilege those from the middle class.

"When I was starting I had to work to pay for school, so I could not spend my summers working on a game with a team. After school I had to take on a few contracts in order to live. All this means that what I can produce will not stand up to someone who has those things taken care of for them. It's not about who does more work either; it's about those who want to support a more diverse industry getting rid of the 'bootstrap it' mindset and working to create space where someone doesn't need to make the choice between having a warm home and making a game.

"It's about looking real hard at the boundaries we are perpetuating in the industry. It's about discarding predatory practices like unpaid internships or giving a small amount of funding in exchange for control to a marginalized creator's IP."

Julie Chalmette and Audrey Leprince, Women in Games France

Julie Chalmette, managing director of ZeniMax in France, and Audrey Leprince, co-founder at The Game Bakers, both joined the industry in the mid-1990s. Their desire to create an organisation championing female voices in a male-dominated industry came from the realisation that it isn't necessarily more welcoming now than it was two decades ago.

"When we first discussed creating the organisation with Julie, we talked to a lot of women in our network," Leprince says. "We were hoping to hear from the younger generation that it was better for them than it had been for us, as a result of a general progress of society and mentalities. We were surprised it was not the case."

That's how Women in Games France emerged in 2017, as a non-profit organisation dedicated to the advancement of diversity and gender equality in the French games industry, through training, education, networking and overall support. The keywords to the organisation's initiatives? Staying pragmatic and result-oriented.

"We work so that more women and people of marginalised genders can find their space in our industry and contribute their voice to push the medium forward, especially today when half the players identify as female and only 20% of the developers," Leprince continues "Some of our key actions are for instance building a list of 200 expert women ready for public speaking about games in any area of expertise, or our esports incubator that coaches promising women players to help them get into pro teams."

"The success of diverse teams will lead to more unique ideas, new voices heard, new games catering to a wider variety of tastes"

Julie Chalmette and Audrey Leprince

Three years on, Women in Games France is now a team of 50 volunteers and about 2,000 members across the country, bolstered by the support of big names such as Riot Games and Ubisoft, as well as French games trade body SELL, of which Chalmette is the president.

"SELL is very committed to promoting a culture of gaming that is both diverse and inclusive: not only to women, but also to seniors or disabled people," Chalmette says. "Video games are mainstream today and it is very important that everybody feels welcomed."

Leprince is also co-founder of Wings Interactive, a fund targeting game creators from underrepresented genders.

"Wings is in many ways born from our work at Women in Games," Leprince says. "It made it clear how money was the key to change. And how many additional hurdles women game entrepreneurs -- already very rare -- had to go through to access funding for their games. We believe the success of diverse teams will lead to more unique ideas coming to life, new voices heard, new games catering to a wider variety of tastes. That it will help accelerate the change of our industry in terms of diversity and inclusivity."

Tanya DePass, I Need Diverse Games

In 2014, in response to an Ubisoft developer blaming the lack of playable women in Assassin's Creed Unity on "a reality of game development," Tanya DePass took to social media to express her exasperation at a lack of characters that looked like her in games. With it, she added the hashtag #INeedDiverseGames.

"I was just frustrated with how things were going in the games coming out that year," DePass says. "I was tired of the same brown-haired, blue-eyed dude protagonists in most games. I didn't set out to be an advocate or activist, I was just mad about video games at six in the morning a little over six years ago. It was very much a lightning in a bottle moment that has kept going."

A few years later, she founded the non-profit foundation of the same name, which seeks to elevate projects, works, and research by marginalized individuals, as well as analyze and critique identity in culture in games through a lens of intersectionality. The group publishes articles, attends conferences, speaks at conventions, holds talks, and participates in other activities that promote diversity across the industry.

DePass isn't just at the helm of I Need Diverse Games. She also does diversity and inclusion consulting, game reviews, editing and writing, consultation on RPGs, and is currently creating Into the Mother Lands -- a weekly RPG, streaming on Twitch, featuring all Black developers, cast, and crew.

She says she's supported in her work by the I Need Diverse Games board of directors and the foundation's community manager, as well as a board of industry individuals who help review applications for I Need Diverse Games' participation in the GDC Scholarship Program -- which allows them to send 25 people to GDC each year who otherwise wouldn't be able to attend due to cost.

DePass adds that anyone can support her individually, or specifically support Into the Mother Lands or I Need Diverse Games through platforms like Patreon and Ko-fi.

But more broadly, she asks that the industry "understand that inclusion isn't caving to an agenda, that the games people are making should reflect the world we live in."

Mayara Fortin, Abragames Councillor for Diversity

When Mayara Fortin started in the Brazilian games industry in 2015, its issues with diversity were all too clear. "All it usually took was a look around the room" -- she was one of the few women present, while women's voices were seldom given a platform or heard at industry events.

"The games industry in Brazil is growing and changing, but so far it mostly fails to reflect Brazilian society," she says. "Over half of the population in Brazil is Black or of Black [descendancy], while less than 10% of people working in the industry are from that group. Over half of our gamers are women, though they are still a minority in our industry especially when it comes to leadership roles and technology.

"These numbers get even smaller when looked at closer: a lot of these women are in areas not directly involved in the game making process, and Black people are rarely in positions of leadership or decision-making."

Brazil is not alone in struggling with diversity, Fortin points out, but her commitment to making a difference has been absolute. She was one of the founding members of the Diversity Council at Abragames, the Brazilian games association, creating a platform from which real change could be made.

"Soon enough we noticed that we were talking about a much bigger and much more complex issue," she says. "It was not just about visibility; it was about representation, voice, opportunities, and respect. So the next logical step was structuring the Council, planning our actions based on potential impacts, as well as opening up the space for other people to join and represent more diversity groups."

Among the many initiatives Fortin spearheaded was a national "Stamp for Diversity" that awarded games companies and events for their representation of gender, sexuality, race, and people with disabilities. Recognising "how alien the terms 'diversity and inclusion' were to many people in the industry," the Council created online resources and materials to improve education and awareness, and partnered with events to ensure the presence of underrepresented groups.

"The games industry in Brazil is growing and changing, but so far it mostly fails to reflect Brazilian society"

Mayara Fortin

Fortin is quick to point out the contributions of other members of the Diversity Council, including Marina Pecoraro, Camila Malaman, Gustavo Arcanjo and Carolina Caravana -- "none of the great work would have been possible without them." There is still a great deal of progress to be made, she says, but change for the better is already apparent.

"I feel that as an industry we are improving and moving towards a more diverse environment one step at a time," she says. "In a way, that is what keeps me hopeful and committed even when I know we still have a long way to go.

"Women, LGBT+ and Black people have slowly been occupying more spaces, speaking up about their issues and points of view. I believe that is the key step for real change."

Gwen Guo, Singapore Games Association

While Gwen Guo is the co-founder and creative director of a respected audio company, Imba Interactive, to the games industry in Singapore she is so much more -- a bedrock of the local community, a committed member of its core organisations, and now chairperson of the Singapore Games Association (SGGA).

Guo was a key member of the team that turned the grassroots Singapore Games Guild (SGG) into a registered society, qualifying its members for the kind of grants and subsidies that help to establish careers. The SGG -- which became the Singapore Games Association -- also bridged the gap, as Guo describes, "between what schools teach and what the industry needs, in order to equip graduates with the necessary skills to be employable or start their own indie studios."

"With SGGA formed, most of these initiatives still stand, since the community forms the bedrock of our industry," she continues. "However, being a trade association means more responsibilities and being more company-centric rather than individual. On top of what we previously did at SGG, we now speak to international stakeholders, government, and corporations to build the necessary bridges between each other."

As an entrepreneur herself, Guo is alive to the way Singapore's cultural and societal norms can stand in the way of the industry's progress. Video games is a risky business, she explains, and while a reduction in government grants since 2015 have made careers in fintech seem more appealing to many, there are larger forces in play.

"The more insidious problem is really society's fear of failure and the constant pressure to afford a house, raise children, and support your parents. What we really need to do is explore ways we can support these game businesses via mentorship and financial assistance so founders can make amazing games without feeling around in the dark when it comes to survivability."

Guo is one of the principal figures addressing these big picture issues in Singapore, another of which is diversity. A regular voice on panels about the subject at events, she was also an early member of the MYSG Allies in Games group, a collaborative effort from women in the Malaysian and Singaporean industries.

"The more insidious problem is fear of failure, and the constant pressure to afford a house, raise children and support your parents"

"We held dialogue sessions to share about the state of diversity in our respective countries, shared stories and played games together," Guo says. "The group also did a fantastic job in ensuring that their local events get more diverse representation. Shortly after I became chairperson of SGGA, I stepped back from the group and focused my efforts on the association instead, while supporting the group in whatever way I can."

One of the next barriers for Guo is better representation for Singapore's LGBTQ+ developers, which she laments is "unfortunately a touchy topic" in a broadly conservative region. While there is no official representative group, the SGGA worked with Sagakaya (of which Guo is also a member) and the queer-friendly platform Prout on the Heritage Game Jam, allowing an event not explicitly about gender identity to be more inclusive. Through consistent action of this kind, Guo believes that further positive change in the Singaporean industry is possible.

"We [still] have a serious lack of women founders in the indie game and tech space, save a handful who I have utmost respect for," she says. "However, there has been a heartening rise of indie studios who have more than 40% women employees -- albeit male-run. I am hopeful that there will be more diverse leaders in the gaming space in the next five years, as employees may eventually become founders one day."

Outi Laiti, University of Lapland

Outi Laiti wears many hats. In addition to her work for the University of Lapland, she is project manager at Finnish Pensioners' Federation, one of the organisers behind the Sámi Game Jam, and a consultant for several games and related projects.

As an Indigenous Sámi herself, both her studies and her work with the game jam centre around personal interests, exploring ways to empower Sámi people through games development.

"Games have always been a part of my life," she says. “I think I was around four years when I programmed my first lines using Commodore 64 so that I could play. Sámi culture is the core of my being, but games have been a solid part of it. I like to think of this as an 'old ways of knowing, new ways of playing' type of thing."

On the drive behind the game jam, she says: "Games are much needed in Sámi culture and, in my opinion, the ways of producing these games are as important as the final piece and what it includes. After all, Sámi people have always made and played games, so we can be cultural consultants in gaming projects but also game developers. This just needs a spark to become a roaring fire, as we also have a history of colonisation that had an effect on gaming."

Laiti is also involved in projects to make gaming -- and specifically esports -- more accessible to elderly people. She was a key part of the Eläkeliitto Netikäs project, which collaborated with Lenovo Finland and its esports team, the Grey Gunners. In addition to organising a live event where people could see the Grey Gunners in training, she is helping to plan a league with another elderly esports team, Senior Fighters.

Laiti is even working with Finnish libraries on events to introduce tabletop role-playing games to the elderly -- although this had to be piloted online due to the pandemic.

Her ongoing work in its various guises is all about bringing down the barriers to underrepresented voices -- barriers, she says, that are fortified by a lack of resources.

"Our games are mostly serious games and funded by other projects, where Sámi are cultural consultants," she says. "We had the privilege of having games industry sponsors when organising Sámi Game Jam, and support is still needed in future. This support can be anything, like supporting Indigenous game developing events financially, to organising game dev tool workshops and sharing tool knowledge or collaborations.

"Elderly people also need support and, most of all, acceptance as players. Promoting gaming through their lifespan, and seeing the elderly as potential customers -- as individuals, not as a group."

Astrid Refstrup, Triple Topping

"Our first business pitch did not have one game, but was a pitch on how to make the best workplace."

Astrid Refstrup co-founded Copenhagen-based Triple Topping with Simon Stålhandske in February 2017. Since then, the pair's vision of the type of games it wanted to make evolved, but it stuck to that idea of building the best workplace.

"I believe we need to work more actively with creating a safe workplace," Refstrup says. "Alcohol is a big part of how we network in the games industry, and especially in Denmark. [But] if alcohol is the main social reference, many people are actually left out. This is why we don't serve alcohol at Triple Topping -- people can arrange going out themselves, but I don't think I should advocate for a drinking culture by serving my team beers."

In one of the GI 100 nominations advocating for Refstrup's inclusion, she was praised for her ongoing efforts to create a transparent, climate-friendly, crunch-free and family-supporting workplace, but also for her willingness to share that experience and knowledge with others. The studio's employment contract and handbook are both available on Triple Topping's website for anyone to read. They include salaries, as the studio has a flat pay structure.

"Everyone gets the same -- I make the same too, because I want people to focus on making the most amazing games, not compete with each other," Refstrup says. "I want to send the signal that everyone in Triple Topping is equally valid to the company and what we do."

Finding the right balance in terms of working hours to avoid stress and burnout has also been at the core of Triple Topping's vision.

"I want to send the signal that everyone in Triple Topping is equally valid to the company and what we do"

Astrid Refstrup

"Working fewer hours is possible even for that person on your team who will keep trying to convince you that they love working 24/7," Refstrup says. "We debated [having] a four-day work week, but ended up with a solution where we work five days but leave earlier.

"There is not one right solution. But one [piece of] advice I would give people is that they should focus on what life situations the whole team has and what challenges it gives them. One example is when people with kids go to the office in the morning, so much work has been done while they were taking care of their kids -- parents therefore end up working nights or weekends to compensate. But if I let everyone leave at the same time, no one has to compensate.

"Oh and then there is the free baby stroller. Dads in Denmark can take paid leave but very few do, and I can't force them to do it. I designed a taking leave bonus, so if anyone in the team takes parental leave, we will give [them a] stroller… Hint hint, men!"

Hasnul Samsudin, former Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation

Last month, Hasnul Samsudin was appointed head of Sony Interactive Entertainment WWS Malaysia. It was a significant moment -- an undeniable show of faith from one of the foundational companies in video games, and a new chapter for one of the single most important figures in the evolution of the Malaysian industry.

Samsudin has worked for and with the Malaysian government, developing the country's digital industries, for much of the last 20 years. As video games grew in popularity all over the world, they became a more and more important part of that strategy -- and Samsudin was right there, getting to know pioneering companies like Gamebrains to better understand how the government's Multimedia Development Corporation (MDC) could help them to thrive.

"When I first started to look at supporting the local developers then, I was also an enthusiast who saw the potential of the game industry," he says. "I essentially immersed myself in Gamebrains, which was one of the only companies then to understand game development and the business… I worked within the MDC, our partners and the government to bring awareness of the opportunities of growing and developing the game industry."

While he didn't act alone, Samsudin was instrumental in establishing the framework in which a sustainable industry could grow -- strategies for talent development, mentorship, funding, technical infrastructure, and access to international trade shows were all established, allowing more and more game developers to emerge.

"We should try to be more open to those who are enthusiastic to enter, and mentor and guide them to be the best at what they do"

Hasnul Samsudin

Some of these concepts, like the IPCC funding programme, are still going after 15 years. Others have evolved to become even greater, like the Level Up KL developer conference, and the Level Up Inc. talent incubator -- a current or former home to leading Malaysian studios like Kurechii, Kaigan Games and Magnus Games.

"A lot has been done to make the global game industry aware of what Malaysia has to offer, but I still think there is a lot more that needs to be done," Samsudin says. "I am glad to see that we have studios now that have become internationally recognized for both the products and services that they create. Companies like Streamline, Passion Republic and Lemon Sky are working with the biggest studios in the games industry on the most visible products in AAA."

Samsudin left his role at the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation to join PlayStation, and he will now be able to contribute to the country's industry in different ways. One area he is passionate about is diversity, and ensuring that new generations are aware of what is needed to build careers in video games.

"It is more critical now than ever to be open to [get a] diverse talent pool to enter the industry. I always felt that the general public sees the industry as a black box, and that it is extremely hard to get in. But more and more, the tools are becoming accessible, and from a very young age the line between passion and vocation is becoming a blur.

"We should try to be more open to those who are enthusiastic to enter, and mentor and guide them to be the best at what they do."

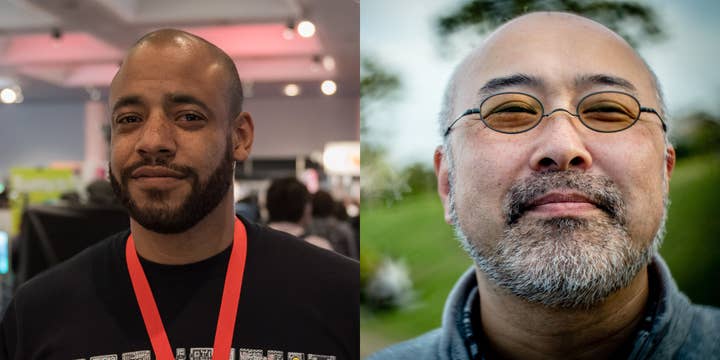

Shouichi Tominaga and John Davis, BitSummit

As much as Japan has played a pivotal role in shaping the games industry over the decades, the country's indie development scene hasn't always been well supported.

Eight years ago, a group of developers at independent studio Q-Games set out to change that, creating an exhibition where studios and developers like them could showcase their work. Shouichi Tominaga, John Davis, and James Mielke put together the first BitSummit in March of 2013, with the help of their employer, Q-Games founder Dylan Cuthbert.

The first BitSummit was a closed event hosted by Q-Games, but it attracted 30 creators, about 200 attendees, and a fair bit of international media attention. Since then the event has grown immensely, drawing more than 17,000 attendees in 2019.

"One of the major roles of BitSummit is to revitalize the Japanese indie game scene"

Shouichi Tominaga

In 2015, Tominaga and a group of volunteers formed the Japan Independent Games Aggregate (JIGA) to oversee and put on the event. Tominaga serves as president and chairman of the board of JIGA, which is also represented by its vice president Hisashi Koshimizu of Pygmy Studio, as well as Skeleton Crew Studio's Masahiko Murakami and Davis.

"One of the major roles of BitSummit is to revitalize the Japanese indie game scene," Tominaga says. "We also want to expand the definition of indie games, rather than narrow it down. BitSummit is not the only indie game event in Japan, but it is the biggest and we hope that BitSummit will continue to stimulate the games industry, encourage more people and companies to try new and unique things. Ideally, we'd like to see an increase in the variety of channels for creators to share their work with the world."

BitSummit's impact extends far beyond Japan's borders, something Davis helps with as the self-described "foreign face" of BitSummit. He coordinates with overseas attendees and runs satellite events, like the internationally touring BitSummit Roadshow, which helps to showcase Japanese games in foreign markets.

Tominaga is still with Q-Games as a creative director, while Davis has since started his own consulting firm, BlackSheep, where he helps developers with the usual problems like landing funding or launching worldwide, as well as helping them make their games more diverse and providing feedback on people of color in their stories.

Both Tominaga and Davis expressed their gratitude for the help of numerous volunteers who ensure BitSummit goes on, and Tominaga also mentioned the Kyoto government, which has been supporting the show since its second event in 2014.

As for what they need in terms of help from within the games industry, Tominaga says BitSummit is always looking for sponsors who share the event's vision, while Davis says the best way to support him would be "to continue supporting events like BitSummit and continue to make content that represents the diversity of the people who enjoy games."