Abbey Games: Survival through a singular vision

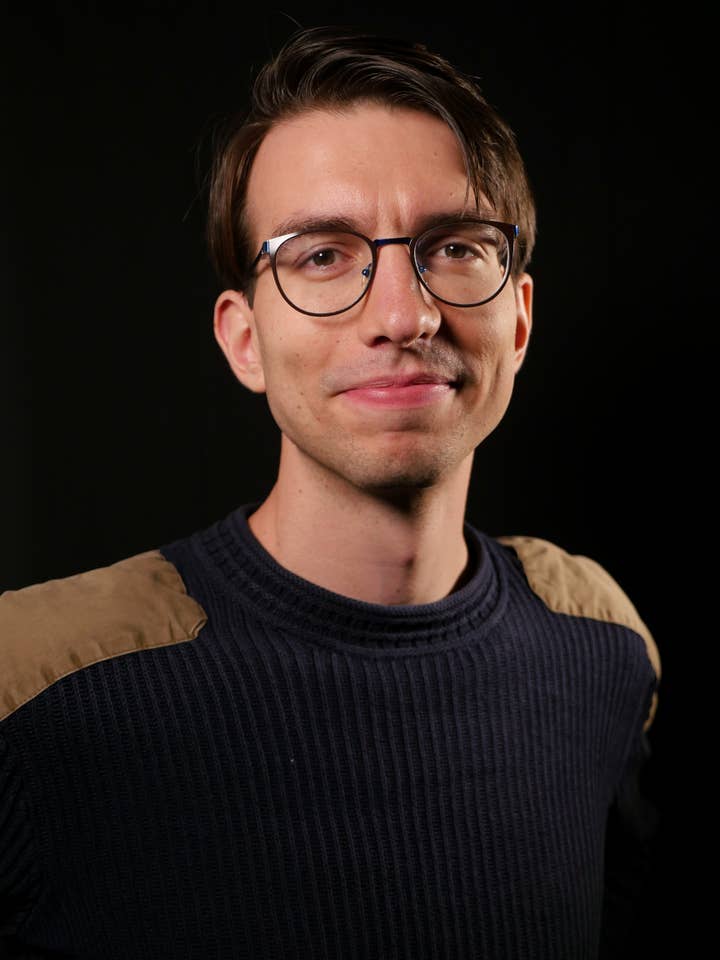

Co-founders Adriaan Jansen and Manuel Kerssemakers tell the story of the studio's rise, near-collapse, and year of gradual recovery

When Dutch studio Abbey Games first started in 2011, the team consisted of only its four co-founders, most of whom were still students funding their first game, Reus, with loan money. It was a success.

But after six and a half years, three games, and a team at least three times the size it started with, Abbey Games terminated all its employee contracts in 2019 due to struggles with its most recent title, Godhood. One of the four founders departed, leaving creative director Adriaan Jansen, gameplay programmer Manuel Kerssemakers, and artist Maarten Wiedenhof remaining at Abbey to work on a game that had received a lukewarm reception, and to decide the future of the studio.

So what happened?

Now, one year after the studio's downsizing, Kerssemakers and Jansen have had plenty of time to reflect on what went wrong, and where Abbey Games will go next. Speaking to GamesIndustry.biz, the two are candid about the wrong turns Abbey Games took, with Jansen summing up the situation as stemming from Abbey's founders knowing how to make games, but not how to build teams.

With Reus, he says, it was easy for the four co-founders to collaborate. The four had a shared vision of a studio with a flat structure where everyone had equal say. But with most of the team was still in school, Jansen was the only one of the four able to work full-time on Reus and thus was able to steer the ship. Reus did well, and allowed the studio some room to grow for a second title.

"Once we finished Reus, we had a lot of money," Jansen says. "And that makes us all crazy, of course. So we started to talk. We always knew how to make games, because we're all very technical. We had a good sense of what was hard to make and what was easy to make. But we did not necessarily have that [sense for what it takes] to run a company; we were pretty idealistic.

"If you talk long enough, everything can be a good idea. There are arguments to be made about everything"

Manuel Kerssemakers

"So when we started Renowned Explorers, the first thing we did was hire a lot of people. We didn't have jobs yet for anyone. We just hired like four or five people, doubled the team."

At the time, Abbey was working out of the same building as Vlambeer, which frequently worked with individuals on a freelance basis. Abbey wanted to be different. But when the new employees joined the studio, there weren't really specific jobs waiting for them to do, so everyone just worked on whatever they wanted. That's how Abbey Games ended up with its own game engine -- two people on the team wanted to build it, so that's what they did.

"It sounds a bit like we were just doing everything in chaos, which in hindsight is probably true," Kerssemakers says. "Of course, we had long and expansive conversations about everything. Like, 'Is this a good idea? Should we do it?' But if you talk long enough, everything can be a good idea. There are arguments to be made about everything."

Even with the self-described chaos, the pair say that the second game, Renowned Explorers, was also reasonably successful, so they began preparing the team to work on Godhood. While the four co-founders continued to embrace their original ideal of a flat structure, as the team grew, they recognized that some kind of structural change was necessary.

"Most of the people we could call friends, right?" Jansen says. "We talked with each other on a very equal basis. That was a culture that already existed. But we also started to acknowledge for the first time that we needed to have some sort of structure and leadership, but we didn't necessarily know how to mash those two things together.

"And on top of that, the personality of the four founders was that most of us wanted different things, but we were not very confrontational about it. We were just thinking, 'As long as we keep talking about it, we are going to find something.'"

Abbey Games's founders hired someone to be the company CEO, which they thought would allow them to focus on development rather than on management tasks. But this quickly became a hierarchical problem: while the founders technically employed the CEO, the CEO was also serving as their boss when they were acting as developers. The result was that Godhood didn't have a single, unified vision. Everyone was simply working on whatever aspect of the game was most interesting to them personally.

"This very democratic and open culture made it easy for a lot of takes on the vision to be pursued at the same time," Jansen says. "So we could say, 'We're going to make something that looks like this.' And then people would think, 'It's going to look a bit like this, I'm going to put a lot of effort on making specifically that part shine.' But that part might not be as important as that person thinks it is. Or maybe that person just doesn't care as much for the whole idea and just wants to see that part become bigger."

"This very democratic and open culture made it easy for a lot of takes on the vision to be pursued at the same time"

Adriaan Jansen

Jansen cites Godhood's city as a specific example. The city is intended as a progression layer, but because so many of the developers put extra effort into it, "the actual core loop of the game just starved."

As Godhood neared release, the Abbey Games team knew it had issues. Jansen and Kerssemakers say that the developers all agreed about what was working and what wasn't, but there was no one to unify the vision and right the ship -- everyone was complaining about everyone else's parts of the game not coming together, and power was too distributed for anyone to have an impact on the overall direction.

Which brought Godhood to its Early Access launch in August 2019. It did not sell well, and multiple team members were burnt out. When a sale on the game a few months in didn't improve matters, Jansen says they knew the studio wouldn't last until January in its current form. Employees were given notice, with budget to pay them for two more months, and by the end of 2019 Abbey Games was reduced to three of its founding members -- its "most technically involved" founder departed the company voluntarily as well.

But, Jansen says, the remaining three were determined to finish Godhood and "at least make it a decent or good product, because that's just on our honor." Without a monetary incentive and no real hope for the game's success outside a decent amount of Steam wishlists, they started working on free patches for the game that focused on one or two key aspects each.

By August of this year, Abbey Games had a product it was at least happy with. With the help of freelancers -- including former employees -- the founders focused on the game's core loop, abandoned chasing ambitions they were no longer technically able to fill (such as Linux compatibility), and managed to bring the game from 54% positive reviews on Steam up to 70%, with 73% positive in the last 30 days. Player retention also improved, and community conversation in the game's Discord is far more positive than it used to be.

Most importantly, says Jansen, the team is happy with how Godhood finally turned out.

"Quality-wise, I think you really just have to look at yourself," he says. "It sounds like a very silly thing to say, but in the end we are game developers. And if we don't know if we're making something good or not, then we're probably in the wrong business... Looking at yourself is the most important thing. It doesn't necessarily guarantee success...but at least you can look at yourself and say, 'This is good. I like this. I made it.'"

Kerssemakers suggests this is a simplification.

"This whole thing about communication and vision where we went from 12 to three people -- there weren't 12 definitions of success anymore, but just three, and in the best case just one. So it's easier to feel it's going well. It was easy to sort of mislead this and think, 'Is this fun? Well, it has to be fun, because otherwise we can't pay the bills.'"

Jansen thinks there are some key takeaways from the story of Abbey Games. For example, he recognizes it was a "weird idea" to bring in an outsider to fix the studio's leadership problems when the founders didn't have a clear vision in place to start with.

"Another thing is the power of culture itself," he continues. "I think culture trumps structure in the sense that the culture is more powerful and has more impact than the structures that you put in place. Even if you say, 'We're going to do this differently,' if the culture is still the same it's just not going to work."

"We went from 12 to three people -- there weren't 12 definitions of success anymore, but just three, and in the best case just one"

Manuel Kerssemakers

Kerssemakers adds: "Throughout the years that we're talking about, we never really changed our culture too much. But we did change our structure quite a lot. Like we did different CEOs and different boards. We did production planning differently. We had separate project teams for the engine and the game, or not. So a lot changed.

"Ironically, the more we focused on structure, the worse it became. I think it's because the structure gives you a false sense of security. Whether you're doing scrum or you're having a board meeting, the only thing that really matters is what kind of people are doing that and how they interact with that structure."

Abbey Games is still recovering, but it's close to being able to pay off its debts, and the studio will ultimately survive. However, Jansen and Kerssemakers aren't interested in trying to grow for now. The three remaining founders are finally having fun making games again, and now they have a chance to figure out what ambition they want to chase going forward. Jansen says they recognize how lucky they are -- most studios with headlines about terminating all employee contracts don't ultimately survive.

For the foreseeable future, Abbey Games isn't interested in trying the studio experiment, and won't be scaling up. The team will continue to work with freelancers as needed, but if they ever decide to hire more employees again and build out the studio, Kerssemakers says that at least one of the founders will need to step up into a management role and focus less on game development.

"We're not looking for growth for growth's sake," Jansen concludes. "If somebody would give us a big bag of money and say, 'Now grow your studio and make something really cool,' -- making something really cool, we feel we have a better grip on doing right now. But we are still afraid that we will fall into the same traps that we fell in five, six years ago. Or at least, we don't know how we would not fall in that trap yet.

"That's something that we're working on. We're talking about it. But we don't have that as a first ambition. We have to scale up enough to make a cool new product and that we feel comfortable with, but we don't need to grow."