The risky business of sexuality in games

Games with sexual themes have always been difficult to distribute and sell -- is the games industry ever going to catch up to the rest of entertainment?

Despite its universal relevance to human nature, our sensibilities often interpret sex and sexuality as an uncomfortable subject. The games industry is certainly no stranger to this phenomenon, and it has yet to fully embrace sex as a source of narrative or mechanical significance. There have, of course, been many attempts, but whenever sex is mentioned in relation to a video game, the general assumption is that it must be either pornography or parody.

This is unique among the various forms of entertainment media that we consume today. Film buffs have Brokeback Mountain, literature enthusiasts might cite Lolita, art critics will perhaps mention Manet's Olympia, and there are thousands upon thousands of acclaimed pieces of music that discuss sex and lust. While all of these art forms have their cheaper, more exploitative works, it's difficult to imagine any director, painter or novelist arguing that working with sex as a core theme is inherently cheap -- so why is this the immediate assumption in the games industry and is it perhaps time we re-evaluated it?

One industry veteran, Brian Shuster, certainly thinks so. Well known in web development circles, Shuster was instrumental in the development of web 1.0 and the foundational development of web 2.0. He became frustrated with what he describes as "the flat web" because of how it handled social interaction.

"Among the many things adults do when they meet and fall in love is to be intimate with one another"

Brian Shuster

"I look at what web 2.0 really turned out to be -- Facebook, Instagram and Twitter," he says. "It really is depressing, in terms of socially isolating people and generating hostility between them."

Shuster had much higher hopes for the web. In the early '00s he envisioned a less asynchronous experience, in which people would not simply post statuses followed by responses, but interact with one another in three-dimensional virtual spaces, attending conferences or performances that involved millions of concurrent users. In his own words: "I figured we could stop people from having to travel across the world to Las Vegas -- spending a huge carbon footprint, not to mention millions of dollars -- to put up displays, when we should be able to do all of this digitally."

Shuster realised the perfect test bed for his ideas lay in the world of MMOs. As a fan of the genre, he saw potential in MMOs for a more mature kind of interaction during his time as a player of the now defunct Asheron's Call.

"I'm out on a quest with...my clan, and a lady shows up and wants to join us. Everybody immediately stops what they're doing and spends half an hour just chatting, talking about where they're from, doing a little flirting, and I realise that this just makes sense," he says. "This isn't like talking to somebody on a dating service, it's much less pressure and far more natural. We're actually engaged in an activity together, and while we're doing it, we're standing around, talking, socialising. From that genesis grew something where the primary focus was to take the negativity out of social media and add in the real fun, positive, socialisation aspects."

The fruits of that experience became Utherverse -- a "content-agnostic social network, designed for adults to be able to connect with other adults in a low-pressure 3D environment." Very much recognisable to anyone who has played an MMO, Utherverse allows players to create an avatar and wander freely through its many worlds, interacting with both the environment and its human inhabitants. One of the most popular worlds within Utherverse is Red Light Centre, an adult-themed setting that includes everything from theme parks to cruise ships to bars. For Shuster, Red Light Centre is the inevitable response to our lack of desire to embrace sex, not just in the games industry, but in the wider media world.

"We've had some fun games, we've had a whole lot of action games, now it's time that somebody did something serious and made people think and feel"

Al Lowe

"People actually try to sneak adult content and sexual content onto other social networks," he says, "but among the many things adults do when they meet and fall in love is to be intimate with one another. We've tried to make Red Light Centre a very natural place for people to relate to one another in that environment. We're not forcing sex down people's throats -- we just want it to be available as a feature, just like it is in the real world. It's fun, it's part of being an adult, but it's not the only thing about being an adult."

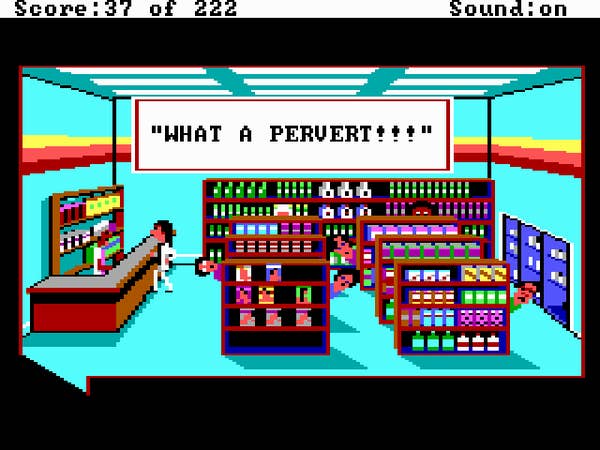

Sierra Online veteran Al Lowe believes that the reluctance to embrace adult themes is rooted in financial issues. Having created the Leisure Suit Larry series, Lowe is very much the godfather of sex-related games, with several decades of experience on the subject.

"I think the turning point was when the accountants took over the management of the firms" he explains. "Suddenly, all of the decisions were based on how many copies the project will sell and what level of funding should be allotted to it."

From Lowe's point of view, a lot of what he was able to achieve at Sierra was a direct result of owner Ken Williams' hands-off, no-budget approach: "He stayed the hell out of the way. He would give you the resources you needed to do the job, but he wasn't micro-managing. Instead, he said 'make a game that you would like to play and other people will enjoy it as well'. That's why each series of games had such unique personalities, because they reflected the personalities of their creators."

Even in the '80s, however, Lowe was contending with the kind of censorship that Shuster finds so frustrating on the modern web. Radio Shack, which made up a third of Sierra's software sales, outright refused to stock Leisure Suit Larry. According to Lowe this was due to the owner's status as a born again Christian. Today, Lowe sees the public as much more liberal in their attitudes towards sex and sexuality, which is why he finds it so puzzling that games are, as he puts it, "still very immature" in their attitude to the subject.

"I think we're long overdue to have a serious game about serious topics" he explains. "We've had some fun games, we've had a whole lot of action games, now it's time that somebody did something serious and made people think and feel. I'm hoping that's going to be soon."

"The average gamer is in their mid 30s and the perception that games are for kids is completely wrong"

D-Dub Games

Lowe sees the race towards realism as a major factor in holding back mature, sexual content from being taken seriously. Referencing his time at Sierra, Lowe describes how they actually attempted a test run at an FMV version of Leisure Suit Larry. "We tried a screen test for a Larry game and... it was painful, because the lines that were funny when a cartoon character said them were cringey when a real person said it. Somewhere that tape exists and it isn't something you want to see."

Ultimately for Lowe, there is no one right way to approach the subject of sex in games. "There are many wrong ways," he begins, "but to find the right way all you have to do is make sure that it pleases you and that it pleases the people around you. Most of us are typical, most of us are like the rest of us. There are atypical outliers, but for the most part if you want to make a game, make a game that your friends like. And if you like it and your friends like it, most of us will like it too. The proof is in the pudding."

Shuster and Lowe aren't alone in their desire to represent what is, for most of us, a significant part of everyday life. D-Dub games, the creator of the GTA-like BoneTown, was also inspired by real-life experiences in a social setting. "The game came from long nights going out to bars and getting drunk" explains the company's founder, who requests to be known only as 'Hod'. "We thought to ourselves, why aren't there games where we can do what we want to be doing in bars?"

Indeed, BoneTown is very much a game centered around being intimate with as many women as possible, often while drunk. There's no question that BoneTown pushes the limits well beyond what many would consider appropriate, even outright problematic. It is unashamedly misogynistic, but for Hod, that's very much the point. "One man's trash is another man's treasure" he says, speaking with the kind of confidence you'd expect from a man who sees seething reviews and angry emails as evidence that he and his team are hitting the right nerves.

"I think there's a general issue that sex and genitalia are so outrageous that even adults shouldn't be able to easily access them"

Bob Conway

Hod's biggest umbrage stems from what he sees as hypocrisy on the part of the ancillary industries that support game development. In particular, his experiences of attempting to organise printing, pressing and distribution have been the source of great frustration. "We were going to print our DVDs with Sony initially because we were using their DRM" he explains. "The day before they went to print, someone higher up in the company saw what was going to happen, and because of their individual moralistic views decided that they weren't going to print them."

While Hod agrees that a company is within its rights to draw the line wherever it wants, he feels that these refusals were never based on company policy, but one individual's personal values. "As a result, I have to go through months of dealing with people, telling them that we do adult stuff, asking if it's okay, and then all of a sudden I find out a higher-up has vetoed it."

This creates a lack of legitimate distribution routes for adult-oriented games, and Hod feels that this separates the games industry from other forms of entertainment. "The attitudes of regulatory bodies, such as the ESRB and its predecessors, plus the fact that games went very corporate very quickly, means you can't do anything with the game equivalent of an x-rated movie" he explains. "The average gamer is in their mid 30s and the perception that games are for kids is completely wrong."

BoneTown came out in 2009, over a decade ago. It isn't a modern game by any stretch of the imagination. In many ways Hod and his game represent not just the attitudes of the era, but the logical conclusion of what Lowe pioneered -- sex-related games, aimed at a straight male audience, designed to appeal to as many as possible by approaching the subject with comedic intent. It's surely no coincidence that they both experienced similar issues with censorship and financing. Today, some might question the value of this kind of game, perhaps even dismissing its creators concerns on those very grounds, but the issues raised by these people extend beyond the horizons of their own studio's work.

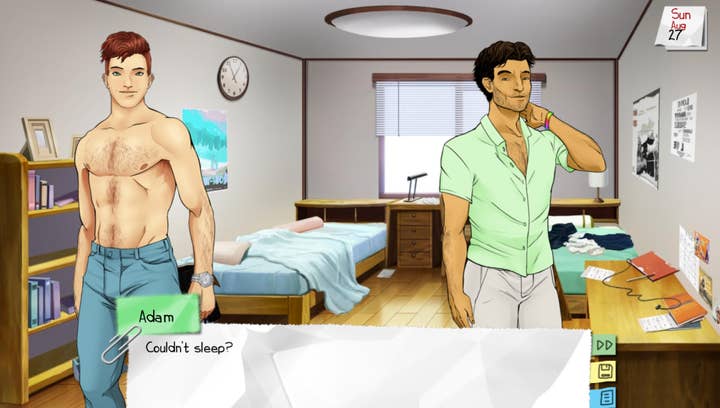

Indie developer Bob Conway, the creator of Yearning: A Gay Story, has seen his work and that of his contemporaries -- Robert Yang's struggles with platforms like Steam and Twitch are another case in point -- suffer from the preconceived notion that sex is inherently inappropriate in a game. Conway's work often tackles the kind of experiences relevant to a member of the LGBTQ community, such as coming out, building relationships and finding love.

"I think a lot of people conflate sex and sexuality", he begins, "and therefore have a knee-jerk reaction to stories that deal with sexuality as being inappropriate. I think there's a general issue, not limited to gaming or the industry, that sex and genitalia are so outrageous that even adults shouldn't be able to easily access them. And that is a problem for developers, not just LGBT ones, but in general, because a lot of romance stories want to include sex."

"People should be able to make the games they want to make. We shouldn't write off entire swaths of games because they contain sex"

Bob Conway

In a scenario similar to that experienced by Hod, Conway describes the fear of being blacklisted from digital purchasing platforms like PayPal and Stripe, both of which have vague guidelines about 'transactions involving certain sexually oriented materials or services' and 'pornography and other obscene materials (including literature, imagery and other media) depicting nudity or explicitly sexual acts'. For Conway, these guidelines are poorly defined, difficult to navigate, and often ultimately determined by an individual acting on their own moral instincts. This makes it extremely difficult to know if you'll ever be able to monetise your work, not to mention the inevitable stigma that comes along with being "banned from PayPal."

However the wider issue here, at least from Conway's perspective, is how this miasma of disapproving attitudes and punitive distribution routes might negatively affect other budding developers. "I think that games are valuable in their own right and people should be able to make the games they want to make," he explains. "We shouldn't write off entire swaths of games because they contain sex."

Conway's work and attitudes represent an evolution in how designers are thinking about sex in games. Traditionally, it has been easy to dismiss, because sex has just been a noun, a naughty word, something to hide behind a fade-out, or cut out of your game entirely for fear of repercussions. Yet Conway is approaching the subject in a new way, with fresh ideas about how and why sex should be a part of the industry. He's pushing the medium forward in terms of how the subject is handled.

Al Lowe and Hod have presented sex as parodical, and you might construct a reasonable argument for why it was a necessary stepping stone to get to this point. But Conway's work is more subversive, and it's that necessary subversion and the push against established norms that comes with it that makes his work so compelling. Sadly, it's also why he's facing so much uncertainty.

Comparatively, Dr. Esther MacCallum-Stewart, associate professor of games studies at Staffordshire University, is more optimistic about the trajectory of sex in games. In her role as an educator, she regularly sees how the attitudes of game design students, many of whom will go on to shape the industry's future, are changing.

"The students I'm teaching today see their sexual identities in a much more complicated and liberal way than their predecessors" she says. "They have no problem with queer students in the class. A lot of them identify as fluid or bi because they just don't know yet. They're thinking in a different way and they're used to doing it. It's just not a big deal to them."

"The game design students I'm teaching today see their sexual identities in a much more complicated and liberal way than their predecessors"

Dr. Esther MacCallum-Stewart

MacCallum-Stewart is also keen to point out that sex is mechanically troublesome at the best of times, remarking on how messy, silly and awkward it can be. But perhaps most importantly, that making love is a subjectively different experience for all of us. "You don't want it to have actual mechanics because then you've got to win at sex" she states, before adding "and winning at sex is really hard."

MacCallum-Stewart then goes one step further by pointing out that, even if we were to discover appropriate sexual gameplay mechanics, they wouldn't neccessarily have to be about sex in order to work. She illustrates this point through an anecdote from a tabletop gaming convention which she attended.

"This lovely young guy was pitching his game idea to Zev Shlashinger, from Z-Man Games. He wanted to do what he considered to be a really cool, edgy game, in which you're a drug tycoon, selling drugs to people. You need to sell lots of drugs, go up the chain of supply, rough people up if they step out of line, and get your cartel to be the biggest and the best. Zed's response to him was: 'If this is such a good game, why can't you change the theme? Why can't you make it about mining? If you set it in the 1920s, you've got a completely different atmosphere. It's now about drug dealers and beating up addicts and poverty-stricken desperation. All of this stuff then suddenly becomes problematic.'"

This aesthetics vs mechanics dichotomy is not a new one, and traditionally, in the study of games, aesthetics and mechanics have been seen as binary opposites, but MacCallum-Stewart feels that this is demonstrably inaccurate. She cites instances of people picking Peach in Mario Kart, not because they wanted to be a princess, but because her AI was too good and they wanted to take her out of the pool of opponents. Jill Valentine in Resident Evil had bigger pockets and it was easier to get to the gun quickly with her.

"They weren't necessarily playing her because they wanted to play a female character" she explains, "but because she was a ludically effective choice for people who wanted to have a bigger inventory and be faster."

Ultimately, MacCallum-Stewart feels that sex, sexuality and gender are all going to find their place in the industry eventually. "Sex sells and gender sells" she begins. "As a player, I've always wanted to see people like me in games. One of the key things I teach my students is that games are big enough now that we can have games for everybody. Saying that I want more queer/trans/gender fluid stuff in games is not restricting anybody else's rights, because there are just so many games."

If there's anything to be taken from the combination of opinions expressed in this article, it's that sex is not only an important subject for many game designers, but also one that inspires a truly diverse and often contradictary set of attitudes. Bob Conway and Hod, despite being miles apart in terms of creative style, both feel that our industry's distribution routes are stifling creativity. Brian Shuster is looking to the future for a more optimistic and adult way of depicting amorous relationships, while Al Lowe feels that we've had our moment and squandered it. Esther MacCallum-Stewart, encouraged by her experiences working with younger developers, is convinced that the size of the industry bodes well for sexually diverse games.

In particular, MacCallum-Stewart's comments seem to suggest that the very thing Shuster was yearning for all those years ago might be just around the corner. A younger, more open-minded generation is about to take the reigns. Along the many developers already out there, both big and small, who intend to continue making sexuality a part of their work, no amount of PayPal bans or conservative boycotts are going to alter the way they've been viewing sex for their entire adult lives.