Shattering Muslim stereotypes with Islamic Relief's mobile game

Ultimatum Games' Shahid Ahmad explains why an idle clicker was perfect for the charity

International aid charity Islamic Relief recently released its first video game with the aim of not only raising money and awareness of its work, but also improving the representation of Muslims in games.

The organisation was looking for a way to portray the complexity and scale of the work it does -- from disaster relief to building sustainable sources of food and water for communities around the globe -- in a game that counters negative portrayals of the religion's followers.

Islamic Relief spoke to multiple developers, but one that was recommended by the British Game Institute's Rick Gibson was Ultimatum Games, the independent studio of Shahid Ahmad, formerly head of Strategic Content at PlayStation. Ahmad believes he was a prime candidate for two reasons.

"First, I happen to be a game developer," he tells GamesIndustry.biz, "and second, I happen to be a lippy Muslim, unashamedly talking about standing up for the religion and representations of Muslims in the media -- although I've been toning down in my old age, because [getting lippy] doesn't seem to do anything."

Ahmad had been playing a lot of idle clickers in the run-up to this project and thought the format would be perfect for what Islamic Relief was trying to accomplish. For a start, clicker games are incredibly accessible to a broad audience -- and interestingly, they actually appeal to the traditional hardcore player as well.

"I saw a stat that 80% of the people who play idle clicker games also play hardcore games on Steam, and that blew me away," Ahmad recalls.

"The other thing I really liked about the format is it allows you to depict the stage-by-stage, work-based and project-based nature of what an international charity does. There are lots of stages involved in building a school, for example, and it's very easy to depict those in an idle clicker -- here's the first stage, tap away, now get a manager to direct some people and do it automatically, then on to the next stage. Even stuff like emergencies and trucks, it all seemed to show that an idle was well suited.

"Nobody can ensure the game is fun, but idle games are easier to make because they don't have too much mechanical complexity. That makes it more manageable. And we already know they work, we know that's compelling and engaging as a mechanic."

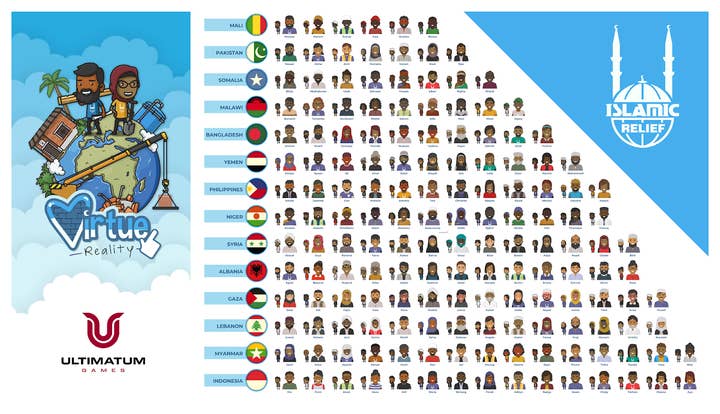

The result is Virtue Reality, a mobile title that sees players tapping their way through the various stages of international aid projects around the world, starting with a microdam in Mali and a shelter in Pakistan. Players tap to generate money for the project, gradually unlocking managers that can automatically handle each step and starting on the next stage.

The game was developed by Ahmad, along with Rob and John Donkin of Bad Viking, with the Ultimatum boss emphasising: "This game wasn't made by Muslims, it was made by three game developers -- one of whom happens to be a Muslim."

"Have you ever seen a game where all the characters are different shades of brown? All smiling, doing good work, saving lives. That's not been done before"

And the fact it was made by game developers -- "this sort of thing is usually picked up by an agency that doesn't understand video games" -- has led to a great start for Virtue Reality. The game accrued thousands of downloads in its first two days, and is highly rated on both app stores.

Ahmad has, in the past, been highly critical of the way free-to-play business models work in mobile, and with Virtue Reality he had a chance to prove it can be done ethically. All in-app purchases go directly to Islamic Relief for their aid efforts, and even the ads are centred around the charity. In fact, Islamic Relief actively turned down the option of advertising other products (thereby further monetising the game) in order to keep everything on message and take advantage of the opportunity to teach players about its work.

"I was really impressed with them," says Ahmad. "They could have said to allow any old ad and monetise them, but they said no. They wanted the message to be clear, just their stuff. They were prepared to take a hit to keep the consistency of message. How many people are prepared to do that?"

He continues: "I'm really happy with it. It turned out to be a nice little game. It looks good, plays well, gets the charity's aims across and dispels stereotypes thanks to the vast array of characters. Have you ever seen a game where all the characters are different shades of brown? There are some white people in there as well, of course, but it shows the true spectrum of humanity. And they're all smiling, they're all doing good work, they're all saving lives. That's not been done before."

Representation is enormously important to Ahmad, and this title gave him the chance to "combine the two dominant strands" of his life. To date, most Muslims in games "usually tend to be terrorists you have to shoot," but Virtue Reality introduces a wide array of managers and specialists to help you on your project.

Their religion is not vital to their role in the game; instead these characters are hired for their expertise. Ahmad believes subtle yet positive depiction is the way to improve representation, not only in games but in all areas of life.

"If we can come up with the video games equivalent of non-Muslims singing 'If he scores another few, then I'll be Muslim too,' then we'll be okay"

"It's about normalising mainstream Muslim activity as opposed to pushing people to be more inclusive," he says. "The way you get more people to see that Muslims are not necessarily a threat is to see Mo Farrah winning races, to see Mohamed Salah doing the sujud after scoring a goal, to hear Liverpool fans singing 'If he scores another few, then I'll be Muslim too.' They're in the pub singing that, and that to me is beautiful. That's a start... It's about progress."

When asked what the industry can do more to improve the representation of Muslims -- perhaps looking to the blockbuster AAA games as much as (if not more than) independently developed charity titles -- Ahmad observes that this is not just a question about video games, but about the mainstream audience.

"That audience does not like or tolerate risk," he says. "There's no one out there, no matter how good their reputation, who is going to get the budget to create something that's a blockbuster and that's risky. The whole point of a blockbuster is that it's meant to have minimal risk and maximum production value.

"Society as a whole is actually way more conservative than we appreciate and it takes time. The reason we have stereotypes in the media is because of the drip-drip effect over decades, centuries -- there has always been animosity between Christianity and Islam. The point is that the undercurrents that fuel this divisiveness don't just run deep, they've been running for centuries. You can't shift society to suddenly say, 'Oh yeah, Muslims are alright.' It doesn't happen overnight, it takes time."

Ahmad sees growing signs of acceptance and more positive attitudes around the world, pointing to the election of Ilhan Omar, the first hijab-wearing member of the US Congress. While Omar has undoubtedly received hateful comments, her presence in the Congress is a step towards improving the wider perception. He also believes the public is "actually a lot less hateful on whole than we might be led to believe by the media."

"For the last four or five years, I don't recall the last Islamophobic or racist incident on the street against me personally," he says, by way of example. "But if you read my timeline a few years ago around the fear that was being stoked up, it was clear that I was being affected by the fear as well, concerned about my wife who wears a hijab and so on. So normalising the dialogue would be a good start.

"I don't think there's an easy answer. Normalising the discussion and not being embarrassed [will help]. We need the Muslim equivalent of non-Muslims being able to sing, 'If he scores another few, then I'll be Muslim too.' If we can come up with the equivalent of that for video games, then we'll be okay."