Loot boxes a matter of "life or death," says researcher

Academics discuss their studies and concerns surrounding game monetization at FTC workshop

In the opening panel of the Federal Trade Commission's workshop on loot boxes yesterday, representatives of the industry and consumer and watchdog groups gave the federal regulator a lay of the land on the issue, detailing what they are, how they work, and why some people have problems with them. There was a measured tone to the meeting that apparently didn't sit well with York St John University researcher Dr. David Zendle, who later led off the day's discussion from a panel of academics.

"There's one clear message that I want to get across today, and it stands in stark contrast to mostly everything you've heard so far," Zendle said. "The message is this: Spending money on loot boxes is linked to problem gambling. The more money people spend on loot boxes, the more severe their problem gambling is. This isn't just my research. This is an effect that has been replicated numerous times across the world by multiple independent labs. This is something the games industry does not engage with."

"This is so important. It's not something we should trivialize or laugh at or compare to baseball cards. This is life or death"

Dr. David Zendle

Zendle said that problem gambling is "an excessive disordered engagement" beyond the person's control and has been linked to depression and anxiety, can cause financial distress, destruction of families, and even leads to people taking their own lives.

"This is so important. It's not something we should trivialize or laugh at or compare to baseball cards. This is life or death."

While Zendle said his research and others has shown a link between problem gambling and loot boxes, he conceded that it's unclear what sort of causal relationship might exist. It could be that players who get deeply into loot boxes are then more likely to develop problems with real-world gambling, or that people who already have problems with real-world gambling are disproportionately drawn to loot boxes.

"We don't know which of these are true and which of these are right, but in either case, it's a clear cause for concern and not something to be trivialized," Zendle said. "In one case, you have a mechanism in games that many children play that is literally causing a state of affairs that is enormously destructive. And if loot boxes do cause problem gambling, we're looking at an epidemic of problem gambling the scale of which the world has never seen.

"And if that's not true -- and I'm totally open to that not being true -- then you've got a system in which game companies are differentially profiting from the most vulnerable of their consumers. Problem gamblers already have enormous issues in their lives. They don't need to have their money taken away from them through this as well."

Following Zendle on the panel was Dr. Andrey Simonov, assistant professor of Marketing at Columbia Business School. Simonov described his research, which is exploring whether players who engage with loot boxes are doing so for practical, legitimate reasons, or because they're hooked on the gambling aspect of it.

He and his collaborators believed they could start to examine that question by looking at when players turn to loot boxes. They reasoned that if players are opening loot boxes when they seem to be stuck in a game and need a boost to get over a difficult stretch, then that might suggest there's a rational thought process behind it, whereas if they were opening them repeatedly when they seemed to have no need for a boost, that might suggest there were gambling tendencies at play.

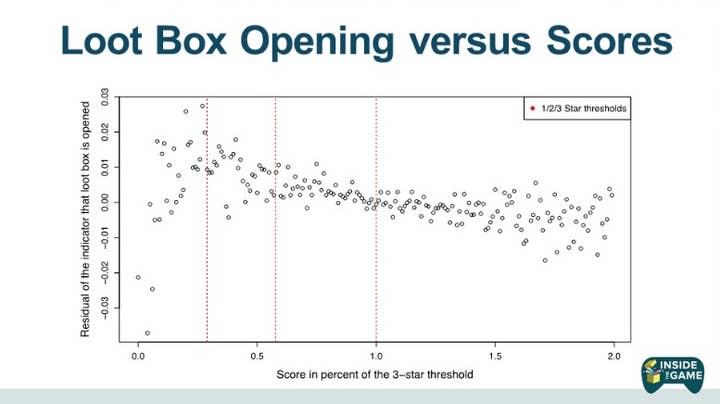

They worked with the publisher of a Japanese mobile puzzle game where the loot box items were primarily functional and centered on in-game progress, and looked at what players' success rates were on levels leading up to their use of loot boxes. Like many mobile games, there were score thresholds players had to meet to pass a level with a one-star rating, and higher thresholds to earn a two- or three-star rating.

Simonov showed a graph contrasting players' scores on levels just before they opened loot boxes. As the numbers approached the one-star point threshold, there was an uptick in the number of loot boxes opened, while there was a general downward trend in boxes opened as players passed higher thresholds.

"So what this shows, and it's consistent with all descriptive evidence, is there's definitely some functional value in how people open loot boxes," Simonov said, adding the caveat that this doesn't mean people only open loot boxes for functional value.

The next researcher up was Dr. Adam Elmachtoub, assistant professor of industrial engineering and operations research at Columbia University. Elmachtoub's research came at the issue from a different angle, creating a model to determine what sort of loot box would make the most money.

At the heart of the model is the idea that every individual consumer values every item differently, and they will keep buying loot boxes until the total value of the items they get in a box no longer exceeds the price they paid for the box. Together with collaborators at Columbia as well as the University of Toronto and the University of Pittsburgh, Elmachtoub ran a number of scenarios and came up with some counterintuitive findings as to which formats would generate the most money for publishers.

"Since there's a benefit for lying [about loot box odds], there must be regulation around this"

Dr. Adam Elmachtoub

For example, they determined that the "traditional" loot box approach where players can earn duplicate items rather than a "unique" loot box approach where they are guaranteed that every item will be new to them actually works in the players' favor. While players bought roughly the same number of loot boxes in traditional or unique models, publishers were able to charge higher prices for unique loot boxes under the model because players were guaranteed new items. So even with duplicates (which the researchers regarded as worthless), players in traditional loot box schemes had a larger gap between what they perceived the items to be worth and what they paid overall.

They also looked at allocation probabilities to find out what the optimal strategy was for publishers, and under their model, the most profitable strategy was the most straightforward: dole out everything uniformly at random. If there are 1,000 items in the game, the best results came from giving each one a one-in-a-thousand allocation.

However, there was one very important caveat.

"It turns out if the seller publishes some list of probabilities and lies about them, the seller can make significantly more money," Elmachtoub said. "There is a benefit for lying. Since there's a benefit for lying, there must be regulation around this."

Elmachtoub said games need to be monitored to ensure publishers are actually following the probabilities they post, and it needs to be tracked not just in aggregate but on the individual consumer level because it's otherwise possible to gain more money by extorting specific individuals.

In a post-panel Q&A session, Elmachtoub talked about the difficulty of ensuring publishers are accurately reporting their probabilities while they are also employing dynamic odds, something the ESA defended in an earlier panel.

"I think that would be a nightmare to regulate," Elmachtoub said. "As the odds are changing, you could never with just a couple of samples see if you're truly adhering to such odds. So that's something I think would be something to worry about in terms of making sure people are sticking to these odds, even if they are dynamic.

"Another unique thing about loot boxes versus baseball cards is that companies can see your inventory. That's a fundamental difference. Being able to take advantage of that would obviously be beneficial to the seller and allow them to exploit more. But also it would be bad for consumers because it would be very, very difficult for them to understand their optimal purchasing strategies in the long run of the game. It would be very hard to anticipate how much money they would need to succeed in the game if everything's updating dynamically."

"I'm trying to shift this conversation away from, 'Just tell me how many hours are allowed' to, 'What are some symptoms... that would indicate there's a problem?'"

Dr. Sarah Domoff

The final academic on the panel was Dr. Sarah Domoff, assistant professor of clinical psychology at Central Michigan University. Domoff spoke about gaming trends among children and parents she's seen both clinically and in her research. One obvious trend recently has been Fortnite, with Domoff saying Epic's battle royale shooter has been played by 45% of children and 61% of teens.

Domoff said it's important when talking about children and games that the discussion doesn't get boiled down simply to screen time. It's also important to consider the context in which they enjoy games; For example, she said a quarter of teens endorsed playing Fortnite during class. And despite the prevalence of Fortnite in kids' gaming habits lately, Domoff said about 75% of parents and children have never played the game together, even if they play it separately.

According to Domoff's research around games and other screen media, there's very limited interaction between parents and their children on mobile devices in particular.

"We heard earlier today that parents have a lot of power to control some of these concerns related to games, but right now things are getting in the way and there are barriers to parents and children interacting around games. This is really problematic because recent research supports setting limits around gaming, and that parent-child communication about gaming could be really important for older children and adolescents."

Domoff also addressed concerns that have been raised from teachers and clinicians she has worked with at Central Michigan University.

"One thing we hear time and again is that gaming is embedded in social interactions among children. Sometimes this can be really good; you connect with your friends and peers on games. Other times, it can be conflictual."

She then turned to definitions of problematic gaming, both her own and the World Health Organization's, and emphasized that the symptoms to look out for aren't just someone playing games a lot or being really enthusiastic about gaming. Instead, it's more about the context of how they engage with games, and the actual symptoms to worry about are when gaming begins to interfere with the child's functioning, when they aren't getting enough sleep, lose interest in other activities, are unable to cut back on playing, and continue or even escalate their gaming despite it having such negative consequences.

Domoff emphasized, "I'm trying to shift this conversation away from, 'Just tell me how many hours are allowed' to, 'What are some symptoms or engagement with different types of screen media that would indicate there's a problem that should be addressed?"

While she didn't endorse any specific avenue of loot box regulation, Domoff emphasized in the post-panel Q&A session just how difficult it is for parents to navigate the details of the vast variety of games their kids could be playing.

"Regardless of whether regulations are coming forth, we definitely need better documentation about what parents should consider, whether from within the industry or from consumer groups such as Common Sense Media, because it's just really complicated and there are so many games for parents to keep up with," she said. "It's such a challenge."