Bridging the gap between games and non-gamers with Twelve Minutes

Creator Luis Antonio on the game's conception and evolution, and his hopes to uplift the Portuguese games industry

When Luis Antonio first conceived Twelve Minutes, the idea was for the game to span a 24-hour period and contain a plethora of ambitious, interlocking interactions. Over time, that scope become much smaller and more contained. And in a way, so too did Antonio's work, as he moved from one of the biggest game studios in the world to working nearly solo on his own game.

Antonio pitched the original idea for Twelve Minutes both during his time as an artist at Rockstar London and later as art director at Ubisoft Quebec. Both rejected it because, as Antonio puts it, it was "never something that aligned with the vision of the studios at the time."

However, he found support for the concept during his time working as an artist on The Witness with Jonathan Blow. While on that team, Antonio says, there were a number of developers "coming and going" who liked his idea, and suggested he learn to program and make it happen.

"[AAA studios] always have these goals that I think are against developers having enough freedom to take risk"

When The Witness wrapped, that's exactly what Antonio did. Initially with support from Microsoft and later with the publishing support of Annapurna Interactive, Antonio began refining his idea into Twelve Minutes. For some of that time, he worked solo. The team now has a total of six people, but everyone except Antonio is part-time.

It's a dramatic shift from his previous experience as an artist at major studios, and it's one that Antonio says suits him well.

"Personally, I think what attracts me to game development is this constant exploration and iteration into interactive experiences," he says. "But the issue with AAA [studios] is maybe because of the size or how they're run, they always have these goals that I think are against developers having enough freedom to take risks. After a while, it just became frustrating to me. A lot of good projects we started ended up not going anywhere because of high-level reasons.

"In indie, I realized that this much smaller scale and the fact that everyone on the team has a lot of different skills lets you iterate on ideas a lot. Just the concept of the designer also being a programmer is huge. Jonathan Blow would have an idea, he would go into a room, and one hour later he would show us what his idea was. Versus AAA, where a designer would write a document, we'd go into a scrum meeting, it goes into the task list of a programmer who implements it, then we all see this kind of half-version of something, then the cycle repeats."

Now as an indie developer, Antonio also feels he's uniquely positioned to draw attention to another issue he's passionate about: the growth of the Portuguese development scene. Antonio studied fine arts in Portugal, but left when he went to work for Rockstar and is now based in San Francisco. After visiting recently, he's sure that the country's industry has plenty of talent -- it just needs a bit of investment help.

"I think we need a couple of Portuguese titles that will make investors believe in the talent and see that we are viable creators"

"I think the main issue is the lack of investment in general in Portuguese styles," he says. "Most games end up being mobile or small experiences. In terms of talent and skill, it's just like everywhere else.

"One of my goals with this project is to help [the Portuguese development scene]. I've tried to get some Portuguese developers as part of the team and do as much as I can for the industry there. I think we need a couple of Portuguese titles that will make investors believe in the talent and see that we are viable creators."

Twelve Minutes is a game about a time loop, where the main character experiences the same 12 minutes over and over again but remembers his prior actions each time and can use that knowledge to make new choices. Antonio says the game was initially conceived as a way to explore player choice, and gradually evolved into an experience heavily tailored by the player's own knowledge and understanding of the situation they're in. It is meant to be highly ambiguous (particularly after the player moves beyond what they've seen in trailers), with no specific direction as to whether the player has done anything 'right.'

"I didn't know at the start what the exploration of the time loop would be about," Antonio says. "But I realized it's about accumulated knowledge that the character has, and the player interpretation of that accumulated knowledge. A character can be learning new things he can use about the characters around him, but if I [the developer] don't tell you [the player] what to do with this knowledge, don't give you objectives or guide you in any direction, it becomes a very subjective experience.

"A character can be learning new things, but if I don't tell [the player] what to do with this knowledge, it becomes a very subjective experience"

"In a very shallow interpretation of [the movie] Groundhog Day, the fact that he could do things the right way in order to 'win' the loop is something that takes away from the experience. [If I did that in the game], I'd be saying you did the 'right' set of actions that allowed you to stop being in the time loop, but if I don't tell you what actions those are and don't tell you that you're correct or wrong, it becomes your interpretation. It gets pretty ambiguous later on. Once you stop trying to do things right, there's a deeper layer I hope players will enjoy."

Realizing that answering my question specifically would ruin the game, Antonio manages nonetheless to respond to my curiosity about how a game where there's no 'right' answer could have an end state.

"A book has a last page, and in a movie after two hours you get the end credits," he says. "In the medium of games, we can do a little bit more than that. You'll reach a satisfactory conclusion to your experience in six to eight hours, but I'm trying hard to make something that's not an ending as we're used to having them. It's a time loop. My first question was, how does an endless experience conclude, rather than end?"

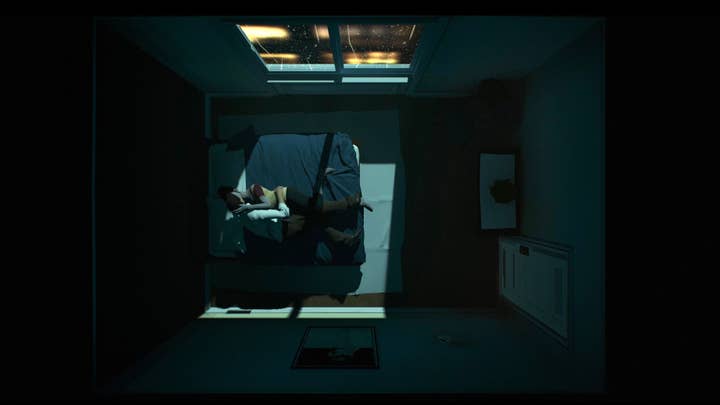

Despite the importance of ambiguity to the game's narrative and meaning, the actual gameplay isn't ambiguous at all. Twelve Minutes is a top-down game, with its only button inputs involving the mouse. The player uses click and drag to pick up objects (which Antonio says are all very easy to find) and combine them with others, and everything is intuitive. A glass of water dragged to the sink is filled, and in turn dragged to the main character's wife is offered to her to drink.

"[I want to have] people not look at games and interactive experiences as just entertainment, but more like a good book or movie"

"Once you know the objects, that's your vocabulary," Antonio says. "When you play a first-person shooter, you don't think about dropping the gun and picking up a stone from the ground. You know that you have this thing attached to you and all you do is shoot and kill other characters. Same with a platformer. You know the vocabulary you have.

"I wanted to do something where you had more than just one or two actions with variations, so I looked a lot at adventure games. The issue with adventure games is that if you play a platform game and you get stuck, you fall, you die, you know why you died. But in an adventure game, you could jump out a window, or combine this object with this other object. It becomes guesswork after awhile. But there's a richness to the environment and experience that more linear games don't have."

Antonio says he wants to combine that richness with the simplicity and straightforward understanding that he sees in platformers and shooters, then wants to ensure it's even simpler. That's because he wants Twelve Minutes to be a game that can reach even people who don't typically play video games, and be just as intuitive to them as most video games are to people who play them regularly.

"My wife does not play games," he says. "Like zero. I remember early in our relationship I tried to play Portal with her, and she couldn't even manage to look around. The concept of using a gamepad and getting comfortable with movement and camera rotation [was not one she understood.] And I realized there is this whole range of experiences that get locked beyond the complexity of interfaces and knowledge you 'should' know.

"When people who have experience in games play Twelve Minutes, they start hoarding all the items and combining trying to see what they do. And they don't go very far. It's very logical, the way things are built. While non-gamers, all they have to do is know how to use a mouse and click. It flows much better for them. They don't think about systems and breaking them.

"There's a moment where you want to prove you're re-living the same day. They [non-gamers] find it immediately, just by thinking. They think, then they execute their thought. People who play a lot of games, especially adventure games, don't think of how to prove it. They just start combining things, hoping they'll unlock it. That's a thing I've always wanted to do, is bridge that gap. Having people not look at games and interactive experiences as just entertainment or spending your time doing something because you're tired, but more like a good book or movie."