People have figured out premium mobile - Ken Wong

Designer of Monument Valley and Florence sees increased competition in the market, reflects on what connects his games

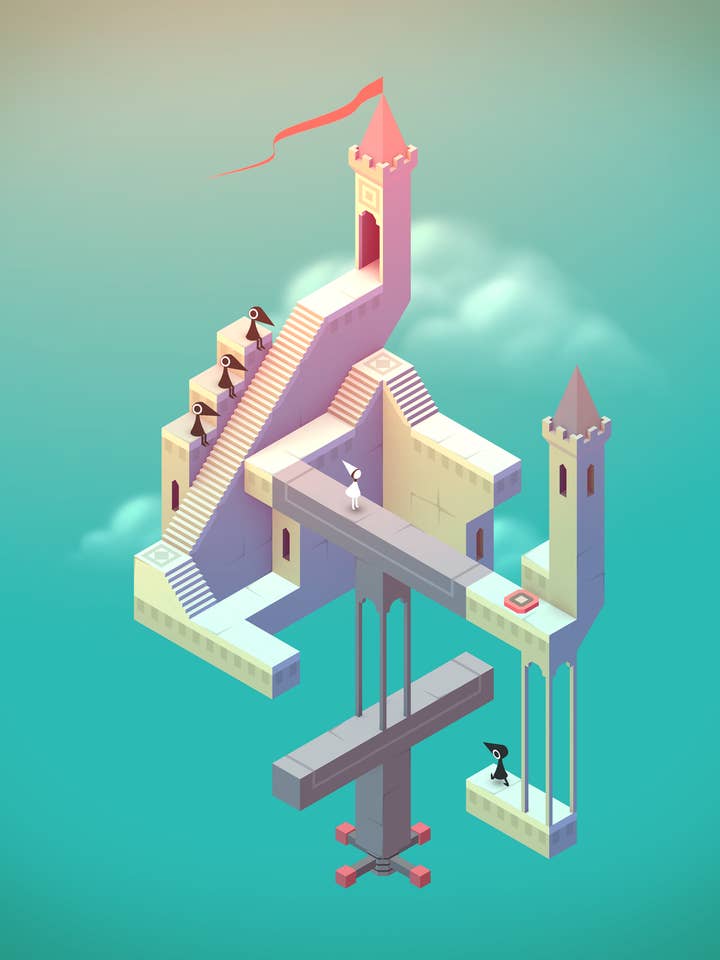

Monument Valley was a surprising hit when it came out in 2014. First, it was the product of Ustwo, a digital design studio rather than a game developer. Second, it was a premium-priced title in an era where the conventional wisdom in mobile had already shifted heavily toward free-to-play business models.

After the success of Monument Valley and a downloadable expansion to the game, lead designer Ken Wong left Ustwo to establish his own company, Mountains. In February, the studio launched its first game, the premium priced Florence, and Wong spoke with GamesIndustry.biz at the Game Developers Conference last month to talk about how the mobile market has changed between the two titles and the response to Mountains' debut title.

"It's still a bit early, but I feel like the reception has been really amazing," Wong said. "We're looking at Facebook and Twitter and people are just moved. We get a lot of people writing in to say the game made them cry, made them cry on public transport, and that people are seeing themselves in the game. That's been incredible to hear. It feels like it's connecting to people on an emotional and personal basis."

"I remember thinking when we launched Monument Valley, there weren't a lot of premium titles to talk about"

Financially, Wong said the studio has been happy with the early sales of the iOS version of the game, and the Android title (which had launched just days prior) was also tracking well. And even though it may seem to be a similar story of a premium-priced app succeeding despite going against conventional wisdom, Wong thinks the surrounding market is very different these days.

"I remember thinking when we launched Monument Valley, there weren't a lot of premium titles to talk about," he said. "You had The Room. You had Sword & Sworcery, a few things here and there but nothing was like a really massive hit. Now it feels like between Monument Valley and a couple other titles like Lara Croft Go... I feel like people have figured out that premium space. And it's difficult, but so is free-to-play. I feel like there's more competition in the space right now."

As for how Mountains makes games in that more competitive field, Wong reached back to the approach he took at Ustwo, which arose from a need to make the game work for a studio which was wasn't focused on making games.

"So the work that actually funded the games team [at Ustwo] was apps and other interactive multimedia experiences," Wong said. "So I felt like we needed to make something they could understand and recognize and appreciate, and that led to a different way of thinking about games, about maybe we bring a bit of app DNA, or a bit more graphic design and motion design. And that led to thinking a bit outside the games industry box--like, let's revisit the idea of what a mobile game is--that's totally informed how we design games at Mountains.

"With Florence, it was the same kind of thinking. Let's take the mobile device, smartphones and tablets. Blank slate. What can we do with it? What do we have? We've got a touchscreen, a microphone, a gyro... How can we make a game experience with that? And that's a different way of thinking compared to when you're working with consoles or PC and you've got a much more traditional audience and there are all these existing patterns to work with."

While Florence's narrative about modern love and its comic visual style have drawn plenty of praise, they weren't the focus at the beginning. Wong said everything stemmed instead from the team's emphasis on exploring a new area of interaction design.

"We were actually looking for a core mechanic," Wong said. "What's a new core mechanic we could come up that's different to anything else? What we were playing around with were jigsaw puzzles. Because you can drag elements on a touch screen, we could do jigsaw puzzles. That's something that hasn't been explored as much, nothing that I can think of. How can we use that to do something, either to make a fantastic digital puzzle we can't do in the real world, or can we tell a story? What we arrived at from those options was telling the story of a relationship where the jigsaw puzzles are metaphors for things being pieced together, or things coming apart? Or what happens if a piece is missing, or what happens when the pieces don't fit together? How can they represent different moments in a relationship? And when we had that idea, it started writing itself, so we spent more time exploring that."

Much of what they discovered in those explorations is readily apparent in the finished product. And while the design of the game and the way it infuses meaning in player interactions is certainly clever, describing certain scenes doesn't really do them justice. Seeing puzzle pieces of a couple drifting apart is a pretty on-the-nose metaphor for them drifting apart as people, but scenes like that can be plenty affecting regardless.

"Maybe we don't have the language yet to describe what's going on there," Wong said. "It's a bit like trying to describe a song and tell a friend why it was so amazing. 'It was like, it had this bit that was awesome, and it made me feel like that...' That doesn't make sense, you just play them the song. Maybe it's easier to write about games when it's very similar to other games you've played. If there's a new team-based shooter, you can say, 'It's like that game, but it does this differently.' With Florence, because we're sort of in uncharted territory, I would say we're really exploring meaning behind interactivity.

"I think about the word 'sensation' a lot. What sensation does this interaction give you that we can evoke? So when we do that interaction in conjunction with imagery or music, what kind of synesthetic effect does it have? All these things combined hopefully takes you back to a moment where you were in a similar place with a partner or an ex-partner and you say, 'Oh right, it's totally like that.' It's partly the power of how a documentary works. You're seeing something that feels very real, but you're seeing it in a compressed amount of time, like hearing about a war, or a journey, or how Apple designed a product. Hearing that all in the space of half an hour or an hour, it becomes a rich story. And I don't really know why that is, but it works."

On the surface, Florence is a very different game from Monument Valley, from the story it tells to the interactions it uses to tell it. But for Wong, they don't seem so different.

"Some people join the dots and some don't," he said. "It's interesting. Most people don't see the connections between the projects, but I do. They're kind of in terms of positioning, and sort of values. Both Monument Valley and Florence are not about winning. And they're not about skill. It's about giving players a really good, valuable time. A short time, but a good use of their time. And every scene, there's something new to see. You're not really repeating things. So in that sense, I think they're very similar."

There's at least one other arguable similarity between the two projects.

"I think a lot of game design is about extrinsic rewards," Wong said. "You're doing this interaction because it rewards you with points, or ammo, or gold. And when you remove that, when you say you're not just going to assign a random thing, the thing itself has to be rewarding. When you finish a chapter in a book, you don't get points for that. They don't give you stars for it. You're just rewarded because that was a good story and you want to see what the next chapter is. And I think, why not apply that to games? Games can be their own reward. It just requires a bit of a different approach."