Mediating the meeting of games and movies

APA Agency's Gina Ramirez talks about her time on both sides of the Hollywood and Games divide

When Gina Ramirez tells people in the games industry she's with the talent agency APA, there's a common first reaction she dreads.

"They refer me to all of their friends who want to be actors," Ramirez laughed, saying a blank stare is another common response. "On occasion, they'll know one of the things we do is celebrity representation. Aside from that, most people just don't know so they ask what we do."

Ramirez spoke with GamesIndustry.biz about that perception recently, and about how it might be changing. While the company has always represented actors for voice-over work and celebrities/influencers for marketing and endorsements, the agency has been expanding its gaming presence in recent years, representing entities large and small. On the one hand, APA represented Capcom for film/TV initiatives. On the other, it helped a writer negotiate a deal with Activision to work on Call of Duty downloadable content.

The agency's work expands beyond the AAA sector as well; APA has represented production company DJ2 Entertainment as it has scooped up rights to make film/TV adaptations for a number of independently developed games, including We Happy Few, Little Nightmares, and Ruiner. They'll represent celebrities for endorsements, influencers for content marketing, performers for live events and tours; they'll even work with developers in their dealings with publishers, or other potential financiers.

"There are a lot of independent companies that could use our resources, but just have no idea who we are or what we do"

"Everybody should be aware of it because there are a lot of independent companies that could use our resources, but just have no idea who we are or what we do," Ramirez said.

She admits that's in no small part a self-created problem, as talent agencies traditionally keep to the background, leaving the spotlight for the talent they represent. And of course, APA is not alone in the field. Agencies like CAA and WME have made waves in gaming at various points, but Ramirez said on the whole, gaming has yet to establish itself as an essential pillar of the talent agency business.

"There are only a handful of individuals trying to make video games work within the bigger agencies," Ramirez said. "I like to joke that when I started this career ten years ago there were about three video game agents and now there's about four. But the opportunity exists."

When asked why games hadn't become a standard line of business for agencies, Ramirez pointed to some fundamental differences in the way the film and games industries work, illustrated in part by her own career path.

During her education at USC Film School, Ramirez interned at a number of firms and discovered a love for the dynamics of talent agencies. After she graduated school and discovered that video game agents existed, Ramirez (a life-long gamer) pursued a career as one. She spent a number of years at United Talent Agency in its digital division and had the opportunity to work with games here and there, but she felt it didn't quite count as working "in the games industry." In 2013, she jumped the fence and took a job with Activision as director of talent and found out just how different the film and game worlds are.

"I think the larger talent agencies struggle with understanding what talent means in the games industry," Ramirez said. "We tend to associate talent with game developers, but it wasn't until I got to Activision and had firsthand experience with developer/publisher interactions that I started to realize the industry may be a little young for labels. On Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, we had Activision's CEO, Eric Hirshberg, writing character dialogue. That's like walking onto a film set and seeing your gaffer rehearsing lines or your actor working on the film budget."

Just as Ramirez had to bring herself up to speed on the logistical differences between the industries, so too was there a learning curve for the cultural differences.

"I think the larger talent agencies struggle with understanding what talent means in the games industry"

"At talent agencies, you're allowed to be outspoken and very confrontational," Ramirez explained. "It's actually a good thing to be able to have that level of communication."

To her initial surprise, Ramirez found the games industry was a little more concerned with polite diplomacy, particularly when dealing with people higher up in the org chart.

"Applying [the talent agency approach] to Activision was probably not as effective," Ramirez deadpanned.

Ramirez said Activision was fortunately understanding of the occasional breach of decorum, and she in turn honed her diplomatic skills greatly over time. (Possibly too much, as Ramirez joked she's having to unlearn some of that behavior now that she's back in the world of talent agencies.)

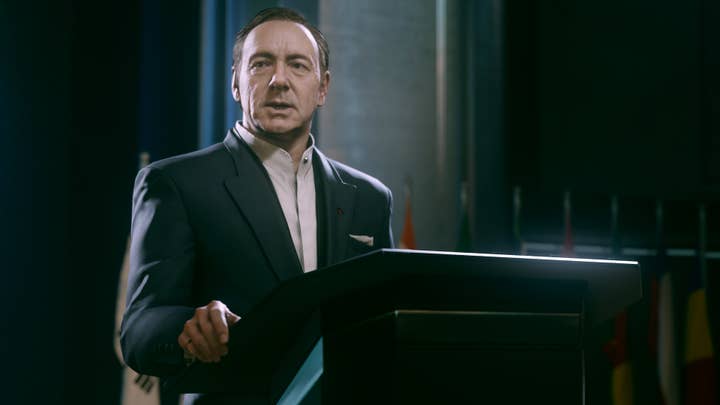

During her two years at Activision, Ramirez helped land a wealth of celebrity talent for the publisher, including Kevin Spacey, John Malkovich, Megan Fox, Chris Evans, Heather Graham, Jeff Goldblum, Rose McGowan, and more. While it wasn't that long ago, even in that span of time she's seen an evolution in the way celebrities and games get together. A decade ago, celebrities viewed video game work as a product endorsement, Ramirez said, charging publishers the same rates they would command to sell soda or sneakers. But during her time at Activision, Ramirez was pursuing the lower rates they would ask for artistic work.

"The idea here is that you're creatively involved with this game," Ramirez said. "You're definitely not running the game; you actually don't want to be running the game. But you're definitely involved with the creative. That was the subtext of the conversations that would happen."

That doesn't necessarily mean Ramirez was having to pitch games-as-an-artform to people. For the most part, she said it was either self-evident to people or it was something you'd never sway their minds about. So the key to getting a reasonable rate was to find the people who already understood the creative aspect of games, and to be willing to walk away from those who didn't.

"That's what most game companies aren't really aware of," Ramirez said. "They happen to fall in love with a specific somebody or they think that person's so perfect."

"I didn't think the gaming industry's stubbornness was going to match the film industry's stubbornness"

Celebrities aren't the only part of the film and TV world that's cheaper to bring to games these days. The entire movie industry's perception of how to work with games has changed.

"When I started, the thought process at the big film studios was, 'If you want to use one of our IPs for a video game, you have to pay us a high licensing fee for it,'" Ramirez said. "Nowadays, you can tell a lot of film studios are seeing video games as a marketing extension. So as opposed to charging really high licensing fees, they're much more either funding their own content or lowering the fees so they can just have more content out there. Because you have to market your product."

While it's clear there's some cozying up going on, the friction of two massive industries interacting with one another hasn't gone away entirely. Ramirez had nothing but positive things to say about her time at Activision, but when she left in 2015 she was just about convinced that getting games and Hollywood to play nice together was impossible.

"They're both very powerful forces," Ramirez said, clearly searching for a diplomatic way to describe the problem. "The short of it is I didn't think the gaming industry's stubbornness was going to match the film industry's stubbornness."

But then APA approached her about signing on to grow the company's footprint in gaming. She knew all about the potential upside to the move, but it was the way APA wanted to go about it that convinced her to try again.

"They were of the mindset of, 'We're willing to listen. We want to do this the right way,'" Ramirez said.

That willingness to play by unfamiliar rules is a good first step toward making the two fields work well together, but more needs to be done. Fortunately, Ramirez has a solid plan of action for addressing the entrenched stubbornness.

"I am yelling a lot," she laughed. "It will eventually have to [go away] because it does make sense for both mediums to work together. They both have very different qualities which, when put together, can lend a lot of value to each other... Talent agents by definition are people who are committed to the growth of others. We're not just looking to place a celebrity or to pitch a developer, we're looking to help you push the medium further and sometimes we need your advice on how to do that. But when we say we're in, we're all in."