ZX Spectrum: An enduring legacy

Why I Love: The Oliver Twins share how they went from nearly missing the boat on the computer to building Blitz Games off a library of 17 Spectrum games

Why I Love is a series of guest editorials on GamesIndustry.biz intended to showcase the ways in which game developers appreciate each other's work. This column was contributed by Philip and Andrew Oliver, creators of Dizzy and co-founders of Blitz Games and Radiant Wolrds. It is a follow-up to their recent column on the BBC Micro, and is being published now as part of the lead-up to the Spectrum 35th Anniversary event at the Cambridge History of Computing Museum this Saturday, October 28. The Olivers will be in attendance, as will Rick Dickinson and a number of Spectrum developers.

If you're 40+ and in the UK games industry then Sir Clive Sinclair and the Spectrum need no introduction. For the rest of you, he was THE boffin of the '80s, the UK's answer to Steve Jobs.

He was bright, eccentric, and often making media headlines, not always for the right reasons. He put Cambridge at the centre of consumer electronics and, more importantly, cheap home computers. These home computers would be the entry point for many kids who would be inspired to pursue careers in the games industry, and for many more who simply enjoy playing video games.

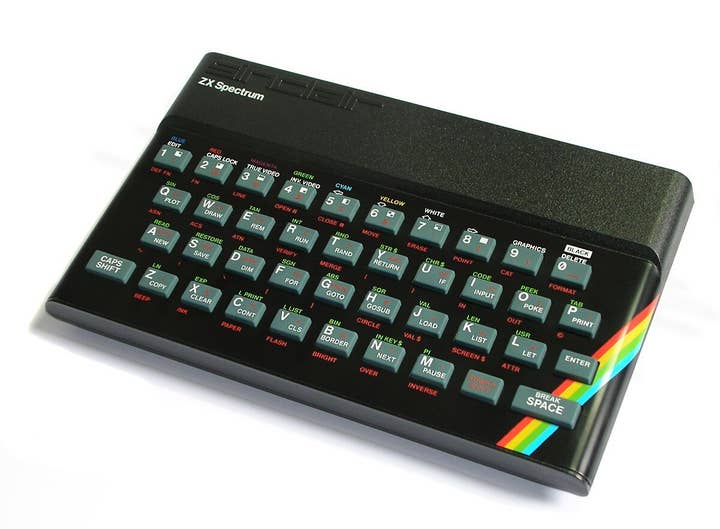

In the '70s, Clive Sinclair was responsible for inventing the pocket calculator, but he soon moved on to selling computer kits. Always keen to drive prices down, in 1980 he produced the ZX80, a computer for under £100. That's still about £450 in today's money, but its closest rivals at the time were two or three times more expensive. He was quick to make improvements and launched the 1K ZX81, with its 'paper' keyboard. Whilst it didn't set the world alight, it proved the perfect stepping stone to producing the ZX Spectrum, a computer capable of colour and hi-res graphics, with another 'interesting' keyboard and graphics comparable to other more expensive computers at the time.

"The fact that World of Spectrum continues to receive thousands of visitors daily is testament to the influence and legacy of the ZX Spectrum"

Lee Fogarty, Curator of WorldofSpectrum.org

Inside the small black plastic casing sat an 8-bit Z80 CPU running at 3.5 Mhz and a video processor that was capable of displaying 16 colours on a pixel mapped 256 x 192 screen. To save memory and increase the speed of displaying graphics, it employed a unique character based colour attribute system, whereby each 8-by-8 pixel block could have a foreground colour and background colour.

But it was the iconic name and design that really made it stand out. Rick Dickinson was the product designer. It was his first project straight out of college and he was thrown in at the deep end. He had to squeeze a full keyboard and many other functions onto a very small area, have keys that moved, and a very efficient and cost-effective solution. The result would become a classic and iconic example of '80s product design.

The ZX Spectrum launched 23 April 1982 at £125 (about £450 today) for the initial 16K RAM model, followed in October by the 48K version for £175 (about £620). Even though the majority of consumers were skeptical that they needed a home computer, several hit the market at around the same time. The Commodore 64, the Dragon 32, and the BBC Model B were all tough competitors, but Sinclair came in cheaper, and with its very small but stylised look, it was one that felt more like a high tech toy. It was within the price range of skeptical parents when their kids wanted a home computer ostensibly for playing games!

Manufactured in the Timex factory in Dundee, the ZX Spectrum led to Dundee becoming a vibrant game development cluster that's still a significant one today, with Abertay University offering the first computer games degree in the world in 1997.

Games for the Spectrum (and many of the other machines at the time) were sold on cassette and initially around £10, which gave a great profit margin for successful games and publishers like Imagine, QuikSilva, Software Projects, and Ocean, who all grew quickly off the back of games like Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy, Horace Goes Skiing, Chuckie Egg, and Ant Attack. Of course, the real geniuses were the Stamper Brothers at Ultimate Play The Game (now Rare) initially with 2D games like Jet Pak and Sabre Wolf, but then came the 3D isometric games Knight Lore and Alien 8.

"Who could have thought that such a compact, almost weightless, package would release so much creativity, invention and kick start a cottage industry of game developers? And yet that was the ZX Spectrum revolution."

Roger Kean - Editor Crash Magazine

All this success culminated in a knighthood for Britain's most famous geek, arise Sir Clive Sinclair, whilst newspapers carried many stories of teenage 'whizz kid' game developers getting rich and buying fast cars.

Software publishers and developers sprang up everywhere to feed this new market. As competition heated up, prices fell and 'budget games', priced at just £1.99, became very popular. These were pocket money games that kids could afford to buy weekly. Mastertronic was first, but was quickly followed by Firebird, Players, Codemasters, and then many more.

With customers buying a game a week, many new games were needed. This led to enormous opportunities for young game developers, and the variety of games available exploded. Whilst creativity was going wild, and the diversity was giving rise to new genres, the quality was very random. However, this gave opportunity to the leading magazines, Crash and Your Sinclair, that thrived on rating and advising players on what they should buy.

We, meanwhile, watched from afar and saw that whilst the Spectrum was the biggest market for computer games, it's one that we had missed... or so we thought. In 1982, we'd made our choice to buy a Dragon 32, because of its proper keyboard. After learning to code on this and wanting more, we upgraded to a BBC Model B. A year later, and after struggling to sell our games on the BBC, we bought an Amstrad CPC 664 with a built-in disk drive. By this point we knew exactly how to make great games fast and this was a relatively soft market, with most good games developers on other computers.

In 1986, after the huge success of Super Robin Hood (our first game published by then newcomer Codemasters), they arranged to convert it to the Spectrum. We started into our next game, Ghost Hunters, and a Spectrum turned up in the post from Codemasters co-founder David Darling, with a note: "Here's a gift, why don't you put Ghost Hunters on to this yourselves and have all the royalties."

We spoke to a friend working at Bath University in electronics and asked him if it was possible to link our Amstrad to the Spectrum, since we had an Assembler ROM and disk drive on this. He produced what we called the SPAM (SPectrum AMstrad) cable within a week. We were able to develop and compile code on the Amstrad, transmit it through the cable and fill the Spectrum's memory in a few minutes. Because both computers ran the Z80 chip, we simply converted the routines that were specific for the Spectrum, the inputs (keyboard and controllers) and outputs (the screen printing and sound). We also included a hidden mastering routine that would save the entire memory to cassette when the game was ready for mass production.

Converting these routines took less than a week and we were then able to produce games almost simultaneously on Amstrad and Spectrum. After that first game, we could get this down to a day or two, simply testing and making a few tweaks for the Spectrum version.

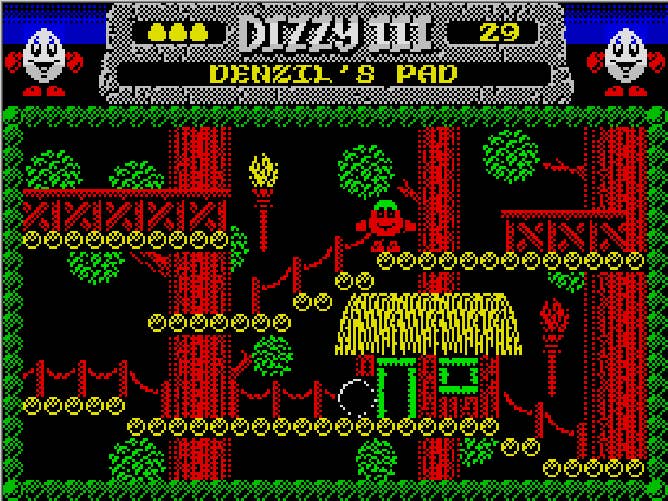

As a result of this incredibly efficient production pipeline and our insane self-imposed work schedule, we went on to produce 17 Spectrum games over the next four years, with 14 becoming UK number 1 bestsellers, including the famous Dizzy games. Obviously we also wrote Amstrad versions of them too, and helped people convert them all to other platforms. We didn't sleep a lot, but we were on a high and at one point over 15% of all games sold in the UK were developed by us. That's when we decided to set up a company and start employing people, many who had learnt how to make games on the Spectrum; that company started life as Interactive Studios but was later renamed to Blitz Games.

Sadly, Sinclair's trailblazing start came crashing down by the mid '80s. He ploughed too much money into the C5, a small electric vehicle, but his 16-bit successor to Spectrum (the Sinclair QL), whilst almost great, fell down in a few crucial areas - particularly its ZX Microdrive tape storage system. In April 1986, Alan Sugar of Amstrad bought the computer business and Sinclair brand for £5m, and a small number of new versions of the Spectrum were produced that gave it another few successful years.

Sadly, 1992 saw Spectrum games removed from most shop shelves, as other computers and consoles took over and its reign was finally over. But the humble Spectrum had sold over five million units, had lasted ten years and had amassed well over 2,000 published games. What a legacy Sir Clive, Rick Dickinson, and the guys at Sinclair Research had created.

More recently, with the advent of the internet, it transpires that the Spectrum had an even bigger influence that we thought at the time. Timex went on to produce Spectrum compatible computers for various places around the world, but more interesting was the number of unofficial Spectrum clones produced, over 50 different models, particularly in Eastern Europe and Russia and because cassettes were so cheap and easy to duplicate. They became very popular games machines, and recently we learnt from the curator of the IT Museum in Ukraine that Dizzy was the most popular video game character in Eastern Europe and Russia in the early '90s.

Even today, clones are still being produced. Earlier this year saw the Kickstarter for the Spectrum Next become a runaway success, with over 3,000 backers pledging over £700,000. Now many Spectrum developers are developing new games for this. Even we are producing an all new Dizzy game for it, Wonderful Dizzy, with programming taking place across Europe by fans of the original games.

So what was it about the Spectrum that made it such a success, and makes it still so fondly remembered by so many gamers 35 years later? We think it's because it was a toy, simple to use, unintimidating, and at a price that most middle-class families could afford. It was a simple entry-level computer that turned out to be great for games. For most of a generation, this was their first experience of computer games. The variety of games was huge and after this, computers weren't just for geeks; they became a mainstream home entertainment platform.

The ZX Spectrum will always hold a special place in our hearts, and in the hearts of many gamers and developers of our generation.

Upcoming Why I Love columns:

- Tuesday, November 7 - Wasteland 3's Brian Fargo on Inside

- Tuesday, November 21 - Voyageur's Bruno Dias on Magic: The Gathering

- Tuesday, December 5 - Lightseekers' Ana Steiner on World of Warcraft

- Tuesday, December 19 - Last Day of June's Massimo Guarini on ICO

Developers interested in contributing their own Why I Love column are encouraged to reach out to us at news@gamesindustry.biz.