"Games are the largest provider of critical thinking education in the world"

Improbable's Oliver Lewis and Nick Button-Brown want to unlock the potential of games as an antidote for "fake news, bias and extremism"

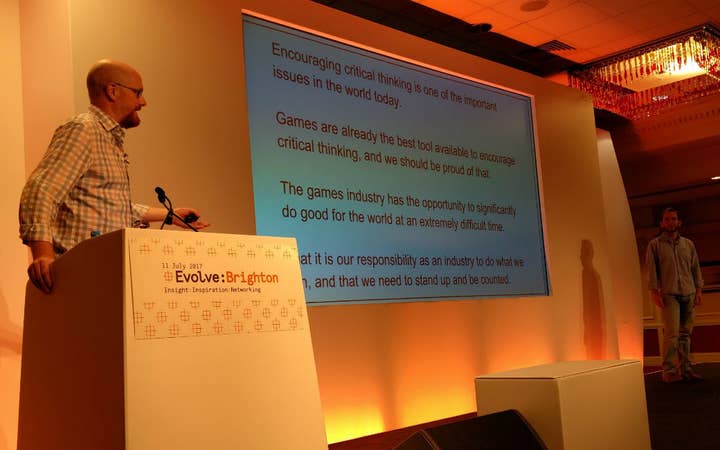

At the Develop conference in Brighton this week, the team behind a new charitable foundation called The Near Future Society asked developers to embrace games as a tool for critical thinking; an antidote to a cultural landscape in which "fake news, bias and extremism" are increasingly powerful forces.

The Near Future Society was initially conceived by Oliver Lewis, a former diplomat and the current VP of corporate development at Improbable. Lewis was joined onstage by Nick Button-Brown, the COO of Sensible Object and one of Improbable's advisors, who became intrigued by The Near Future Society's belief in the positive influence games could have on society.

"We wondered whether games can develop critical thinking, and help us understand how to think about moral reasoning," Lewis said. "We started having this conversation, and we decided that it's much more complicated than 'can they?', and that perhaps they already do."

"People are becoming more extreme. The centre ground is disappearing. It has now become okay to ignore opposing viewpoints, it has now become okay to shout them down"

The Near Future Society's first meeting took place before GDC this year, on the Warner Bros. lot in Los Angeles. "The idea was to get together government, technology, education and entertainment people to talk about how to address the problems of the world," Button-Brown said. "When we met the government people, the thing they were most worried about was fake news, and the impact fake news has on people's opinions.

"People are not questioning. We see it, and we see it in our own lives as well. People are becoming more extreme. The centre ground is disappearing. It has now become okay to ignore opposing viewpoints, it has now become okay to shout them down."

One of the distinctive qualities of games as a medium is the ability to empower players to make choices, and to show the consequences of those choices. Lewis and Button-Brown cited some well known examples of this technique: the admittedly "simplistic" moral split in a game like Knights of the Old Republic, the "Would you kindly?" reveal in Bioshock, and the creeping realisation of The Brotherhood of Steel's true nature in Fallout 4.

"Having spent a lot of time with the UK and the US military, I have an affinity for this group," Lewis said, referring to his experiences embedded with the military in Afghanistan. "[The Brotherhood of Steel] have some really cool kit. But the more you interact with this group it starts to get a little uneasy, then you start to realise that they're a little bit fascist."

Games afford players the freedom to arrive at such realisations, encouraging a degree of critical thinking absent in linear media. This power, Lewis argued, gives developers a responsibility to carefully consider how they present difficult subject matter to the world. Call of Duty, for example, depicts "a type of warfare that's unrecognisable to the modern Western soldier," one where the Geneva Convention and "the reality of the law of armed conflict" are not strictly observed.

"If you go into a mission and your objective is to kill the enemy, you are murdering wounded and potentially surrendering soldiers. That is illegal," he said. "You are potentially using a flamethrower as a weapon. That is illegal. You are told to destroy civilian property and religious buildings. That is illegal. To some extent you're also committing war crimes.

"A lot of game depictions of war are not accurate emotionally, are not accurate operationally, even if they're accurate visually. And as we get towards ever more immersive experiences we have a responsibility to represent that moral reasoning."

"A lot of game depictions of war are not accurate emotionally, are not accurate operationally, even if they're accurate visually"

However, while there are examples of games that don't take that responsibility seriously, The Near Future Society was mainly inspired by the games that already do.

"There are just so many games where, fundamentally, we teach players to think analytically," Button-Brown said. "We teach them to question their environment, and to expect that the people that are talking to them are not necessarily telling the truth all the time. That's what we do in our stories. We're already doing it, and we're actually quite good at it."

"In the earlier part [of the talk], we deliberately held up some of the areas where we could do better," Lewis added. "But only as foreground to say that the games industry writ large is already doing so much good in terms of encouraging critical thinking, and encouraging moral reasoning."

Button-Brown discussed State of Decay and EVE Online as examples of games that use persistence to encourage players to think about the consequences of their decisions. In the case of the former, when one of your companions dies there is no option to restart or bring them back. "I then had to start making decisions about which of my companions I could sacrifice," he said. "That's uncomfortable, even in a virtual world."

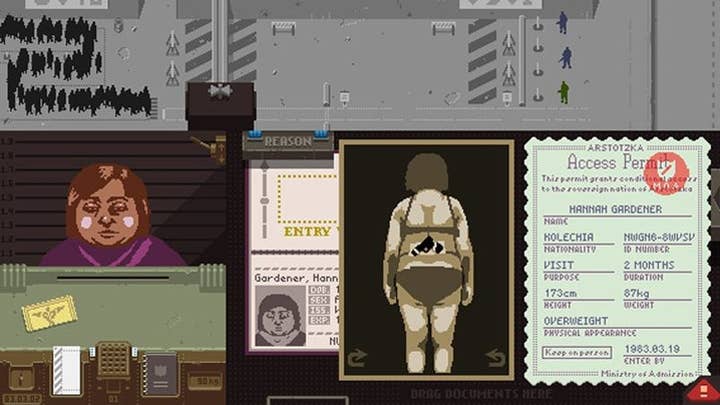

Lucas Pope's Papers Please, which puts the player in the role of a border guard in a fictional country, was also singled out for praise. "It teaches people that there's a grey area," Button-Brown said. "Good decisions in Papers Please can end up with bad outcomes. You're teaching moral action, and also connecting that to the consequences."

Lewis discussed 11 bit Studios' This War of Mine as a kind of counterpoint to games like Call of Duty, in the way that it depicts the experience of the people who suffer the most as a result of conflict. "It induces empathy with the displaced person, the people left behind after war," he said. "Ordinary, normal people who have to try and eke out an existence; to survive and protect the people that we fought for."

"There's a decent chance we're going to have much more influence as an industry over people's morals"

Lewis and Button-Brown aren't the only people to have noticed the potential for games to explore difficult subject matter. Last year, 11 bit Studios launched a publishing division with a stated aim of drawing attention to "meaningful games" like This War of Mine and Papers Please. "There are a lot of players who want those experiences," publishing director Pawel Feldman told GamesIndustry.biz. "We know how to talk about these games. All we need are talented developers."

The Near Future Society has a similar goal, albeit as a charitable organisation rather than a commercial one. Lewis expressed his belief that "social and political taboos" are ideally suited to games as a medium because, through play, "people are much more likely to engage with them." An open brainstorming session at the end of the talk proved that developers are eager to explore this new territory; the Near Future Society will attempt to serve as a conduit between interested studios and bodies that might fund and support their work.

"One of the partners that we're going for is the Roddenberry Foundation," Lewis said, referring to the organisation established by the son of Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek. "We want many of the early projects that we do support to be deliberately utopian. If you want a living wage and [universal basic income], then let's use popular culture to explore that, rather than just having a declaration from Mark Zuckerberg."

Both Lewis and Button-Brown acknowledged that the games industry has a "left-wing bias", and they were very clear that the goal of the Near Future Society is not to tell people how to think. "In the forum in Los Angeles, one of the greatest concerns of the US and UK government that came along...was that this would be propaganda," Lewis said. "What we had to make very clear is that any projects that we do, we'll be very open on who the collaborators are, and indeed what any overt political message is going to be.

"You could say that, within this broad idea of making games more political, you have to state what the politics are rather than hide it with subterfuge."

Button-Brown added that simply reflecting the bias of any given side of an issue would could be "dangerous", and it would also ignore the unique strength that games have to allow the player to explore ideas from multiple angles, and make their own choices. "That's why we ended up at teaching critical thinking," he said, "rather than 'Get Trump out'."

"Games are already the most accessible, arguably the most effective, and the largest provider of moral reasoning and critical thinking education in the world," Lewis said. "Almost without realising it, that's one of the things that you're providing to the global community."

Understanding and embracing that idea will only become more important over time, Button-Brown said. "There's a decent chance we're going to have much more influence as an industry over people's morals. We're going to have much more influence over the way that they think. As people become more immersed in these worlds, it's going to matter more."