"No matter how awesome Star Wars is, we don't need another one"

Ubisoft Montreal's Alex Hutchinson on how diversity in its many forms can lead to better games

Ubisoft Montreal's Alex Hutchinson laid out the myriad ways that diversity can lead to better games in his talk at Quo Vadis this week, from personal interests to the people you hire.

Hutchinson, who was creative director on both Assassin's Creed 3 and Far Cry 4, listed eight principles for effectively managing a creative team, three of which focused on keeping an open mind and embracing distinct viewpoints and personalities. The first principle was established when Hutchinson left his native Australia in 2003 for a job in the US, working for one of the industry's most brilliant minds.

"The first one I learned - and this was a big one at Maxis - was to be inspired by the world outside of games," he said. "This is less and less true [now], but if you imagine a basic inspiration back-drop of any game designer, you'll realise that we all watch the same TV shows, we're all dressed basically the same, we all play the same sort of games. And that was okay for several years, because in the old days the video game landscape looked basically like this."

"We were a very small industry, making games essentially for ourselves."

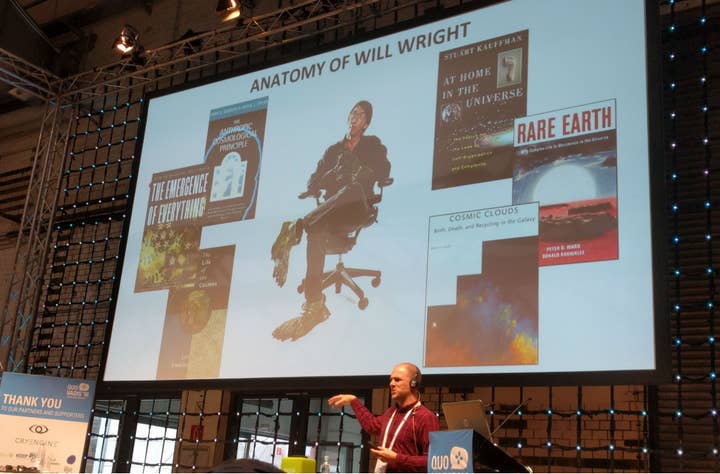

To a great extent, the creative barriers that arose from that situation were exposed to Hutchinson by Maxis' founder, Will Wright, whose interests stretched far beyond the medium to which he had contributed so much. In fact, Hutchinson said, "he really didn't play a lot of games, and historically you might say that would be a problem. For me, that was the key to his success.

"He would have his desk stacked high with science textbooks. He was a collector of Soviet-era space equipment, so our office had things like seats from the MIR station and strange rocket parts from some warehouse out in the middle of Russia. This meant that the kind of games we made were radically different."

An example of this was The Sims, which Maxis had released a few years before Hutchinson was offered a job, and was principally inspired not by an existing game, but by a psychological theory: Maslow's Heirarchy of Needs, which valued and ranked human motivation in a pyramid structure. This esoteric idea was used as a template for one of the most original - and broadly successful - games of its time

"Be fresh," Hutchinson said. "Make sure that your starting point, the first idea you have, isn't how much you love Star Wars. No matter how awesome Star Wars is, we don't need another one. And we certainly don't need any of us to make a second tier replica of it."

As Hutchinson acknowledged, this limited pool of inspiration has started to deepen, but he still lamented that so many of the developers he hires - "lots of game designers, especially" - don't even read a newspaper on a regular basis. Too often, the cultural foundations for the industry's creative ideas remains a familiar crop of films, TV programmes and other games. "You should be [reading newspapers]," Hutchinson said. "You should be going on as many vacations as you can, you should be reading books. Try to bring your inspiration from that."

And that process can be reinforced by another, described in the second of Hutchinson's eight principles: "Casting is the biggest thing you'll ever do." In hiring the right people, he said, the creative process becomes exponentially easier, with "talent" and "attitude" cited as particularly valuable qualities when Hutchinson makes hiring decisions. Just as important, though, is diversity, which Hutchinson said he was "excited to see" becoming more and more important in the industry's approach to recruitment.

"You want as many different voices as you can possibly muster," he said. "You want male and female voices, you want different socio-economic brackets, cultures, countries. The broader the group of smart, talented people who have the right attitude, the more likely your project is to be a success."

"You want as many different voices as you can muster. You want male and female voices, you want different socio-economic brackets, cultures, countries"

But it isn't enough to simply gather this broad pool of voices and inspirations; an effective leader will find ways to let that show through in the final product. Hutchinson addressed a common perception that, when working at the scale of a Far Cry or an Assassin's Creed, team members are effectively factory workers on a line, machining parts for assembly. "In my experience, at least, this is completely untrue," he said. "Obviously, there are certain elements you need to include... But every game I've worked on I've been able to put in elements just to make myself laugh."

Hutchinson used an example from his own career, following his experiences as creative director on Army of Two: The 40th Day, a linear "gameplay, cut-scene" shooter that couldn't have been further from the free-form structure of the games he worked on at Maxis. "I realised I just didn't believe in [that structure] any more, as a vision for the future of games," he said. "So when I was working on Far Cry 4, the only way I could do it was make every cut-scene a joke about how this was pointless."

Rather than push that nagging feeling down, follow the template and machine the parts, Hutchinson embraced his disillusionment and made a bold and memorable choice. When the player's character is captured at the start of the game, the apparent villain of the piece, Pagan Min, leaves the room with the assurance that he will return shortly to help scatter the ashes of the player character's mother. At this point, the player is prompted to escape, and start a 50-hour orgy of wanton destruction. However, if the player waits, Pagan Min will indeed return, the ashes will be scattered, and the credits will roll without a single shot fired.

"For me, I know I'm selling you a game with guns on the back," Hutchinson explained. "There's almost nobody who buys that game who isn't secretly thinking, 'Fuck my mother's ashes, I'm going to shoot some shit'... It's there for people to get a laugh, for purely personal reasons.

"Bu you can extrapolate that throughout almost the entirety of your game. Whatever features you're including, someone needs to care about it."

And the more diversity you have within a team - of background, of experience, and of influence - the more interesting those outcomes will be.

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner for the Quo Vadis conference. Our travel and accommodation costs were provided by the organiser.