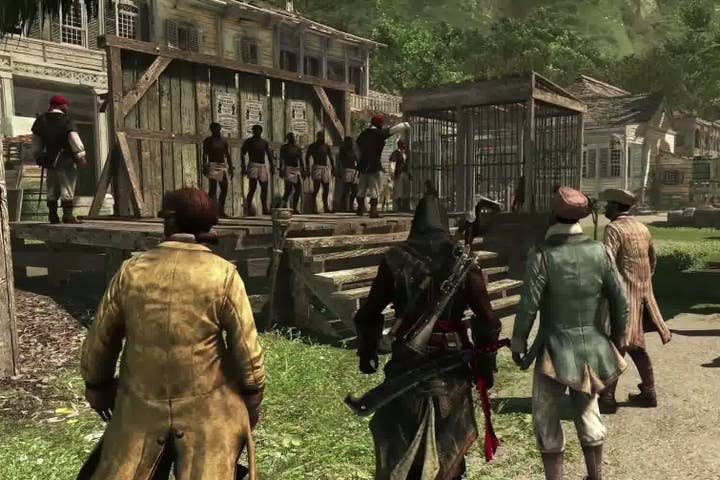

How to make a game about slavery

Assassin's Creed: Freedom Cry devs explain why strong player reactions can be better than positive ones

The original Assassin's Creed set players lose in the middle of a holy war between Christians and Muslims. The latest entry in the series, Assassin's Creed IV: Freedom Cry, grapples more directly with the slavery only briefly referenced in Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag. In between, the franchise has notably used historical treatment of Native Americans and women as backdrops for what is ostensibly intended to be an entertaining and fun AAA thrill ride for players.

Ubisoft Quebec director of narrative design Jill Murray and director of level design Hugo Giard kicked off the Game Narrative Summit at the Game Developers Conference today with a talk on how such sobering subject matter can be put to use in the service of story and design.

Murray started by recapping the story of Freedom Cry, in which the black quartermaster of Black Flag, Adewale, takes on slavers in what would become Haiti. Where Black Flag was a game about indulging in the fun of piracy, Murray said Freedom Cry relies less on fun and more on the idea that players will play for empathy, or a sense of justice. Strong emotions can be an even bigger reason to play than positive emotions, she said.

Murray said dealing with an important theme like slavery made it easier for the entire team to focus on a common goal. While it might be difficult to start development with such a difficult topic, in the long run it could help motivate the team to make a good game, Murray said.

While Freedom Cry used many of the same mechanics of Black Flag, Giard said putting them against the backdrop of slavery adds new context to them. In Black Flag, the player raided plantations for supplies, whereas in Freedom Cry they did it to free slaves. In the former case, when players were spotted, extra guards would come and attack them. In the latter, the guards would split their attention between attacking the player and slaughtering the slaves to try and put down what they saw as a revolt. Murray said it changed player behavior, causing them to embrace a stealthy approach more and dividing their attention between saving their own skin and saving the slaves from execution.

Giard and Murray emphasized that it's OK for developers to make games about other people, even when the topics are sensitive. The key, Giard said, is not to judge or appropriate. Murray said to avoid that becoming a problem, it's important to have all team members do research on the subject.

Researching 18th century slavery in the Caribbean was difficult on a few levels, Murray said. It's difficult to find first-hand accounts of slaves from the period, but they started with the Code Noir, the legal document regulating slavery in the time, codifying everything down to the punishment for a first escape attempt (losing an ear). The developers also found classified ads for runaway slaves, which provided names, tasks, and some other horrifying details (such as a slave who had been branded on each breast with the name of her owner).

On top of fact gathering, Giard said it was important to know how people felt about the subject they were dealing with. Assassin's Creed's own fanbase helped with that, while bits of pop culture like Django Unchained reviews and criticism educated the developers on some of the issues and concerns people have with entertainment that deals with slavery.

Discomfort is a strong emotion, Giard said, and it's one the developers embraced intentionally. In Freedom Cry, some of the overseers who monitored the slaves were themselves black, something playtesters said they had great concerns about. Despite that, Murray it was important to keep that element, not just to avoid whitewashing an uncomfortable historical truth, but to evoke a stronger reaction from players.

"Using strong emotions rather than positive ones gives us a tool to work against player expectations," Giard said. "It allows us to surprise them."

Ultimately, Murray said using a difficult topic can be a way of asking players to deal with a different kind of challenge, an opportunity to provide players with new experiences. And what she took from Freedom Cry is that ultimately, the soul of the game is in "the hard stuff," the things outside of the developers' comfort zone. Games are up to dealing with anything, Murray said, and it's just a matter of keeping the team focused on delivering one coherent vision.