Livingstone Hopes: Why Eidos' President is opening a school

"We need to train kids today for jobs that don't yet exist"

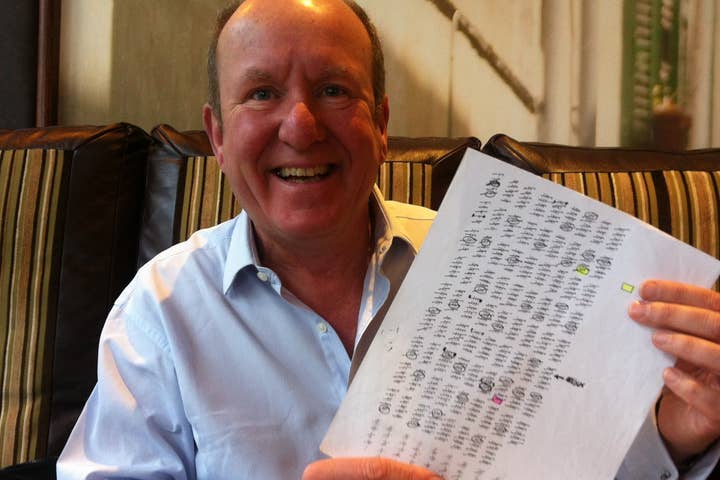

Ian Livingstone is the perennial evergreen of the UK games scene. From co-founding Games Workshop in 1975, Ian moved on to co-writing the Fighting Fantasy gamebook series with long-time friend and collaborator Steve Jackson, earning a permanent place in the hearts, and on the bookshelves of a generation of young adventurers eager to immerse themselves in worlds of incredible fantasy and imagination.

That world creation, the process of interactivity which was so important to that series' success, lead him naturally into the world of games, creating Eureka for Domark in 1984 before joining the publisher in 1992, later overseeing the merger which would see it become Eidos - home of internationally renowned IP like Tomb Raider.

Whilst his role at the company has become less involved since Eidos' acquisition by Square-Enix, Livingstone has been anything but complacent. Turning to the role of industry elder statesman, Livingstone has played a major part in the reformation of the UK's IT curriculum, advising the government on the best way to properly implement training and education in order to raise new generations of creative, technologically literate Britons to take over the mantle of established creators like himself.

In addition to that, he sits on the boards of six major UK bodies which shape industry and government policy, still managing to find time to mentor independent developers on the pitfalls of the modern industry. Oh, and he's managed to pick up an OBE and a CBE along the way. Not too shabby.

In short, he'd be forgiven for taking a well-earned rest, but instead he's taking on an entirely new endeavour: looking to found a free-school in London's Hammersmith borough, which hopes to embrace new methods of teaching to engage children with the core skills of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics) that form the core of the needs of the modern workplace.

The Livingstone School makes its application to government today, with the hope being that a success will mean launching for the first year of pupils in September of 2015. We caught up with the tireless veteran for an insight into his motivations for entering education at the coal face, and why he thinks that things need to change.

"The school curriculum for ICT had been letting us down as an industry and as a nation - teaching kids how to consume technology but giving them no insight into how to use it creatively"

Well, for the games industry in particular you need an environment where the costs are low and the skills are high. I think for too long that's not been the case - for many years there's been almost the opposite case in the UK - cost has been high and skills low. Not low in terms of people being useless, just not living up to our heritage, having got off to such a flying start with gaming in the '80s. It plays to the strengths of the British psyche - high-flying creativity combined with a great knowledge and skills. The school curriculum for ICT had been letting us down as an industry and as a nation - teaching kids how to consume technology but giving them no insight into how to use it creatively - or to create their own technology.

The UK has done brilliantly in terms of creating some blockbuster titles that have done amazingly well around the world, but it could have been so much more. Rather than slipping from third to sixth in the world league table for development we could have been number one, because arguably we're the most creative nation in the world given our brilliance in film, fashion, music, TV, advertising and of course games. I just got annoyed that we didn't have a production tax credit - hence the high cost - and we didn't have a curriculum which was fit for purpose for our particular industry.

I think you're right - I think we often have limited ambition as a nation, we're willing to sell out early doors. Americans, in particular, prefer to scale things to the Nth degree to become global powerhouses in whatever they do. What we do is charming in a way, but it is quite limiting to the economy!

Yes - it seems that people are forced to do all of their fun learning outside of school. My simple common-sense proposition is that we should encourage the fun learning within school instead. I think fun and enjoyment are often seen as past-times rather than learning experiences, which means that they become trivialised in people's eyes as not having any real value. There's a lot of academic snobbery, particularly in this country, that means you're expected to have this 'rigour' in your learning, which translates to misery!

People are forced to learn a multitude of facts, which are largely irrelevant, in order to pass these random memory tests, exams which are basically a lottery - far more to do with league tables than actual learning. That was fine in the Victoria era, when the talk and chalk was designed to fulfil the needs of an industrial society in which children were processed, sent to work in factories where they all needed to know the same skills.

"People are forced to learn a multitude of facts, which are largely irrelevant, in order to pass these random memory tests, exams which are basically a lottery"

That world has totally changed now. We've got high speed broadband, we work in connected environments. The ways in which kids work in particular - they're part of totally connected worlds. You can see by the way they share everything by their smartphones, their activities, knowledge and private details, yet we still ask them to sit quietly in isolation whilst someone at the front talks at them - asking them to note down things which they can always Google at any time! I think you should take facts as a given - you don't need to cram your own hard drive, your brain, with all this data that you could just access at a click of the mouse. It's how you process that information.

For me, real learning can only take place if kids learn meta-skills of problem solving and communication which you can apply to all subjects and promote creativity and collaboration in that process. Why can't teachers accept that they could be equally useful as facilitators? Peer-to-peer learning, from the research that I've read, has a 30 per cent increase in actual learning because kids talking together, solving problems together and learning on their terms, in their language - is far more meaningful than someone talking at them, asking them to memorise facts. So the way we test children is archaic and really needs to evolve. We need to train kids today for jobs that don't yet exist.

So we've got to encourage creativity, innovation and enterprise if we do want to get that mentality.

Well we'll still be offering a broad range of education; this is not just going to be computer science and nothing else, of course. But rather than requiring all kids to do the same 11 GCSEs, and getting A*s in each of them, we'll require them to do a minimum of eight but it's the way… the exams themselves aren't going to be the be all and end all. We're still going to get great exam results but our pedagogy of delivering that is going to be totally different. And so whilst they're doing their As there'll still be time for them to build up a portfolio of projects demonstrating creativity and… a portfolio of work which they can actually use in their interview process or to go on to do further education. So it gives them practical life skills that make them more likely to become problem solvers, risk takers and motivated. It's about the pedagogy and within that computer science is going to sit well because it underpins this world in which kids find themselves.

And it's not just about computer science - don't get me wrong about that [laughs] - it's going to be STEAM subjects, with art, and a choice of the subjects but not requiring everyone to do the same thing. Because so often teachers say 'you're crap at that' and I want teachers to say 'well you're actually very good at that and you don't actually need to do this bit,' - do something that is broader, problem solving and communication skills you can apply to all subjects to have a much richer learning experience.

"You're required to learn quadratic equations - when was the last time you did one of those?"

Well I think primary school is far more relevant than secondary school. We learn through play, it's a pleasurable experience, we learn trial and error through making mistakes, we fall over lots before we learn how to stand up. And we do collaborate, we are playful with our siblings and in primary school that kind of emulates the natural learning.

It's when we get into secondary where it all changes. You're all required to sit still, working as individuals, no team work, no collaboration, no projects that can be assessed as a group - all doing the same thing, it all becomes… that's when the industrial process starts with our children. I think that's so out of touch with where kids are today and we've got to have learning on their terms which is relevant and contextual to their lives. So mathematics for example, it's totally academic at the moment. You're required to learn quadratic equations - when was the last time you did one of those? Because you're given a problem and think 'how am I going to address this problem? Here's the computational bit I have to do and it has an output that is relevant to other problems.' It's OK for the 5 per cent of academics, but for the rest of us maths becomes the most fearsome subject on earth and it doesn't have to be.

Well we're certainly going to bring the educational environment closer to the workplace to give kids life skills, because those with A*s currently aren't necessarily the best students, they just happen to know how to pass exams. The disaffected kids with the Cs and Ds, they might be better employees.

So we've got to make sure that people understand their own value to start off, but to your point we have got a principal designate who is working in a school, is a trained teacher, is assistant head at the moment and will become our head should we get approved. So clearly we're going to have, in our ambition to have, established, trained teachers and staff, at the time we're going to have strong links with industry to make the learning relevant and applicable to life.

"So we've got to make sure that people understand their own value"

Just for our first one, because we hope that this is going to be the first of many! It's because we had such an incredible response to the ethos and the vision and people encouraging us to extend it, as long as we've got the sufficient capacity to do so.

But to your question why, a) we were told by New Schools Network, which is an organisation that helps free school applicants through the process, gave us Hammersmith as a target area of need which has capacity, along with five other London boroughs. And from a personal point of view, Dalling Road, Hammersmith was where I opened my first Games Workshop retail store way back in 1978. So even though it's now a Bosnian-Herzegovinian community advice centre, there's a strong link from a personal point of view. And I don't live far away so there's a definite need there and it happens to fit very nicely with my own history.

It's open to all. There are no barriers to entry.

Well what happens with free schools is that you start off with your first cohorts and then you build year on year. So we're probably going to start with 120, I would hope.

"the hard skills that the industry required - coding, art and animation - were simply not a part of the course"

Absolutely. For seven years I've been chair of Skillset Computer Games Skills Forum, and we mapped out all the university courses that had games in their title - there were 144, I think. We'd only accredited ten after five years, there's more now accredited. But a lot of them were not fit for purpose. They were offering soft skills like the social relevance of games and some basic design stuff, but the hard skills that the industry required - coding, art and animation - were simply not a part of the course. They're doing these students a great disservice, saddling them with debt, thinking they're going to get a job when they weren't. Not particularly good for the industry because we weren't getting work ready students to apply for jobs. And not particularly good for the nation either, because it doesn't really help the economy.

Industry is really welcoming the free school proposal, but obviously it's going to take some years before they'll see the benefit of that. But you've got to start somewhere, like we did with Next Gen Review. We had to start somewhere and managed in the end to help convince Michael Gove to disapply the ICT curriculum and put into place the new computing curriculum, which comes into force in September this year. That could be transformational over time.