Tech Focus: Next-Gen Consoles vs. The Age of Austerity

Digital Foundry on how the console platform holders are factoring in the new economic era into their designs

As all eyes turn to the next generation in gaming hardware, expectations on the level of processing power we look forward to should perhaps be tempered. Call it austerity, call it simply living within your means, the fact is that it's not just governments and families that are counting the pennies - it's the console platform holders too.

In many ways, the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 are very much products of their era. Back in 2005 there was a sense of economic invincibility in the air - and this very much permeates the design of both the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3. Let's take a look at the Microsoft console to start with: originally specced with just 256MB of RAM, it took an impassioned plea from Epic Games to see the console's memory spec doubled to its current 512MB - a move that Mark Rein reckons cost Microsoft a "hefty ransom" Doctor Evil would be proud of: one billion dollars.

"Xbox 360 and PS3 were products of an era of economic invincibility - their next-gen replacements will be built very much with cost in mind"

"We really wanted a hard drive in every single machine; that was something we really wanted but we realised that the 512 megs of RAM was way more important," Rein said in a Major Nelson podcast. "Otherwise you couldn't do this level of graphics if you had to both write your program and do your graphics in 256 megs. Nothing would really look that HD."

The story continues with an exchange that, taken at face value, perhaps helped define the quality standards of the current console generation - while at the same time revealing how desperate Microsoft was to challenge Sony's supremacy in the marketplace.

"So we argued, and argued, and what Tim [Sweeney] did is... he actually sent a screenshot of what Gears of War would look like if we only had 256 megs of memory. So the day they made the decision, we were apparently the first developer they called... we were at Game Developers Conference, was it two years ago, and then I got a call from the chief financial officer of MGS and he said 'I just want you to know you cost me a billion dollars' and I said, 'we did a favour for a billion gamers'."

Leaving aside the woeful Red Ring of Death scenario (which cost MS another cool billion), the boat was undoubtedly pushed out in other elements of the design. Microsoft went to AMD for an advanced graphics core design that featured technology that hit the market before it was even incorporated into PC graphics architecture. Not only that, but both the CPU and GPU were fabricated at 90nm - a production process that was state-of-the-art at the time and nowhere near mature: costly and with low chip yields. Factor in a UK launch price point of just £209 for the base "Core" model and £280 for the hard drive equipped Premium version and the amount of money the platform holder must have been losing per unit was surely eye-watering in the extreme.

To put things into perspective, Sony - launching one year later - was still having problems with the 90nm production process. The Cell processor had to have one its SPUs disabled in order to produce enough viable chips, whereas the RSX graphics core - a late addition to the PS3 spec when it became clear that a second Cell couldn't handle the job - featured a number of cut-backs designed to increase chip yields: the RSX design features 28 ALU (arithmetic logic unit) pipelines, but four are inactive in the final chip. Half of the 16 ROPs (render output units) present in the silicon are disabled. What issues Microsoft had with 90nm remain unknown but there were no known cutbacks in the actual designs. Crucially though, chip yield percentages for the launch period were never revealed - the company may simply have taken the hit, knowing that efficiencies would improve.

"It was a technological arms race gone mad, the irony being that Nintendo's low-tech Wii came along at a substantially lower price-point and in terms of hardware sales at least, blew both of them away"

Sony splashed the cash in other ways of course. Its Blu-ray drive - apparently the cause of its year-long delay - was extremely expensive at the time, but a key component in the company's attempt to dominate the HD movie market. Construction and finish of the launch PS3 unit was clearly a step above the Xbox 360: the additional complexity in the design was self-evident and the cooling system was clearly light years beyond the Microsoft box. Plus of course, every PlayStation 3 came with a hard drive as standard, and the vast majority of them featured WiFi too. Even with a launch price of £425 in the UK, Sony was still losing money hand over fist.

It was a technological arms race gone mad, the irony being that Nintendo's low-tech Wii came along at a substantially lower price-point and in terms of hardware sales at least, blew both of them away. It's widely believed that Nintendo was in profit on each unit from day one since the internals of the Wii are much the same as the Gamecube's, with a boost to clock speed.

Fast forward to today's era of economic conservatism and it's extremely difficult to imagine that we will see anything like this level of brilliant, breathtaking insanity again. Sony and Microsoft's console businesses are actually profitable now: it's hard to believe that either of them will ever recover the untold billions lost at the beginning of the current gen era and both companies will like the feeling of being solvent again. While we can still expect next-gen consoles to be sold at a loss at launch, it's very unlikely that the designs will be as advanced as they were back in the day and the projected return to profit will happen sooner rather than later.

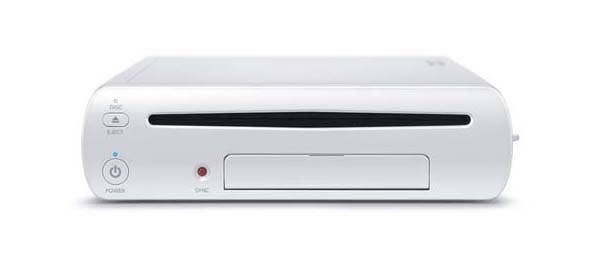

With the new Wii U, we already have some measure of what Nintendo's plans are. This is a unit that attempts to refresh a current gen HD console design with a revised, more efficient tri-core IBM CPU and an AMD Radeon off-shoot that should be relatively cheap to produce. Mature, established production processes are used to maximise chip yields, while components that have collapsed in price over the years will almost certain offer Nintendo most of its competitive advantages - we should expect to see 1GB or 1.5GB of RAM in there, and a decent amount of flash storage to accommodate its ambitious digital download strategy.

Short of a massive last-minute spec boost, it seems clear that Nintendo is building this machine to a price - and hopefully that will be passed onto the consumer. Even the show-stopping tablet controller is based on cost-efficient parts: its screen is larger than PlayStation Vita's, but runs with a significantly lower resolution. The capacitive multi-touch screen we even see on sub-£100 Android tablets isn't present - instead, a less responsive single-touch resistive display is utilised, hence the inclusion of a DS-esque stylus.

"The exotic hardware designs championed by Ken Kutaragi have given way to the concept of cramming as much PC power as possible into a console-shaped box - at a price that's right."

As for the next-gen plans of Microsoft and Sony, just the timing of their new launches suggests some caution and an eye towards economy. The Q4 2013 release window being mooted for Durango and Orbis doesn't just give PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 another year to generate decent profits, it also allows for more ambitious designs to be produced more cheaply. The 28nm fabrication process we can expect to see utilised in both consoles is just moving into mainstream production now with the current-gen Radeon and GeForce graphics cards, but the technology is still expensive and chip yields uncertain. By the time we move into 2013 - where both Microsoft and Sony will need to commit to multi-million production runs - the amount of usable chips will be higher, and the costs to produce them lower.

Elsewhere within the designs we should expect to see other mature technologies deployed. Both Durango and Orbis will feature Blu-ray disc drives; they are no longer the exotic technology they were back in 2006 but mass-produced commodities. Memory has also collapsed in price, though whether 512MB GDDR5 RAM modules will be in mass production at a viable price-point in time for a next-gen console launch remains to be seen. In an ideal world, Sony and Microsoft would be looking at eight chips per motherboard for a 4GB capacity, but current volume GDDR5 production remains at 256MB per chip: this may be the area where the platform holders will need to take a hit initially.

Rumours from a number of sources also suggest that economies are also being made elsewhere. Increasingly stronger and more plausible sources are suggesting that Orbis is based on existing PC parts from AMD repurposed into console form. With PlayStation Vita, the post-Kutaragi era Sony went for off-the-shelf parts that offered the most power and performance for the best price-point. Licensing technology isn't cheap, but it's significantly less expensive than creating a brand new processing architecture from scratch - as Sony did with Cell. Other benefits include the ability to tap into AMD's proven expertise in combining CPU and GPU into a single chip (very useful for later console revisions) plus the fact that developers are simply more comfortable with more traditional processor designs.

And what of Durango? By far the most interesting and plausible report on this comes from VG247, and it suggests a fascinating design choice: that the next Microsoft console will actually contain two graphics cores. This may sound like a somewhat exotic, expensive choice but it could make a whole lot of sense. Two slower, narrower chips should be easier to make than one larger one, and in theory it would be significantly cheaper to incorporate two 128-bit memory buses as opposed to one 256-bit interface. Cooling - a key failure in the original Xbox 360 - should also cheaper and easier to handle as heat would be more evenly distributed across the motherboard.

There would be advantages for developers too, as one source told me:

"In the worst case, you could tile, sending half the scene to one GPU and half the scene to the other, losing some efficiency on border-overlapping geometry; a deferred renderer would lose nothing in efficiency in all the lighting and shading passes," we were told.

"In some ways the lack of exotic hardware is a little disappointing. The grand visions we saw in years gone by have been replaced by a combination of pragmatic realism and economic necessity"

"In the best case, you can parallelise independent operations - for example, rendering the main scene with rendering the shadow map, rendering the different cascades of the increasingly popular cascaded shadow maps, rendering light buffers, rendering different portions of a complex post-processing chain (but post-processing is a good candidate for simple tiling too)."

Way back in 2005, the world was a different place. Sony wanted to re-define computing, replace DVD with Blu-ray HD movies and produce a state-of-the-art games machine. Microsoft wanted a high-end PC in a box, without involving Intel or NVIDIA after unsuccessful collaborations on the original Xbox. To achieve their goals, unimaginable amounts of money were thrown at the problem.

In Microsoft's case it spent a fortune to achieve a year's headstart over Sony - but arguably the effort was worth it. It has achieved wonders in breaking Sony's complete domination of the console marketplace, but stumbled in terms of reliability and build quality. For its part, Sony has seen off HD-DVD (though perhaps did not foresee the prominence of streaming movie services) and produced the most technologically advanced games of the era - but the full extent of Ken Kutaragi's vision for the Cell processor never came to be, and the PS3 with all its triumphs and shortfalls proved to the last console produced under his stewardship.

In some ways the lack of exotic hardware being mooted for the next-gen consoles is a little disappointing. The grand visions we saw - particularly from Sony - have been replaced by a combination of pragmatic realism and economic necessity: both of these machines will almost certainly be PC tech repurposed into games consoles. The challenge for Microsoft and Sony will be to produce a generational leap that matters to a mainstream audience at a price that works: £299, anyone?