Gree: Escaping mobile's middle-class

Andrew Sheppard on the growing dominance of mobile's richest publishers, and Gree International's $35 million bid to close the gap

Just over a year ago, I talked to Gree International's Andrew Sheppard about one possible future for the mobile games market. Digital distribution, he said, has "tipping effects towards winner-take-all," allowing companies with the most financial resources to "crowd out the competition" by spending big, gaining ever greater leverage over the market, applying ever greater pressure to the margins of their competitors.

"Honestly, it's not a good long-term thing," he warned. "If that margin pressure comes too fast it's not going to allow the industry to settle into a state that has more than just a few products."

"It's not just a matter of jumping to the new platform any more... We're back in the 90s, building console games, and that's all there is"

Since then, Gree International has been busy in a number of ways; promoting Sheppard to CEO following a long period of carefully managed transition, and laying off an unspecified number of staff in its San Francisco office earlier this month, indicating that the transition is still not quite over. In terms of product launches, though, Gree International has been relatively quiet, the tangible results of that transformation still mysterious.

At Casual Connect Europe I hoped to learn more about the kind of game Gree regards as the best response to those tough market conditions. In his keynote address, Sheppard made one thing clear from the outset: those market conditions have not changed.

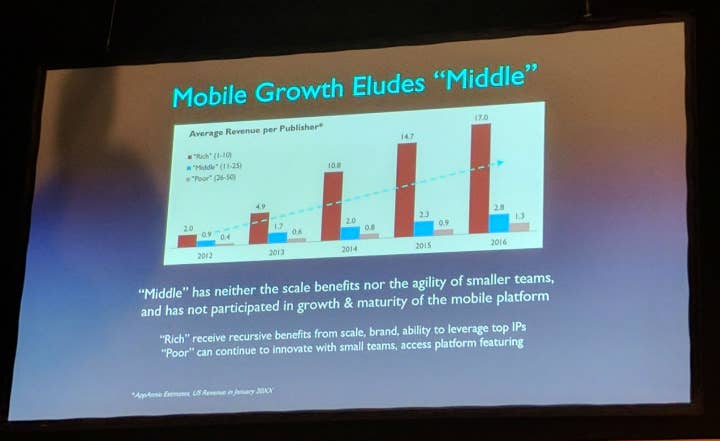

He presented data showing the monthly average US revenue of the top 50 publishers on iOS and Android over a five year period. Those 50 publishers were broken into three groups: the "rich" (1 to 10), the "middle" (11 to 25), and the "poor" (26 to 50). "Poor," he told the crowd, was a relative term, and a little clumsy in this context, but the trend was abundantly clear.

"What we see here is a surprising trend, and we can feel it as developers when we look at the leaderboards," he said. "In a market that's growing so quickly, we see that a lot of the spoils of that growth have accrued to a very small number of people." In a digital marketplace, Sheppard continued, "rich" publishers enjoy "recursive benefits" that yield greater returns with each passing year, while the rest of the top 50 lags further and further behind - and the "middle-class" most of all. The point of Sheppard's talk was not to chide the top ten for their success, but to offer constructive methods for those outside to make their futures more financially stable and secure. Nevertheless, that message was presented in the context of a market where upward mobility is steadily disappearing.

When I meet Sheppard a few hours later, the conversation quickly turns to Pokemon Go; unquestionably the most significant mobile launch since we last met, and one that was received by some as evidence that the top ten remains a possible dream. Sheppard doesn't see it that way. If anything, he says, the success of Pokemon Go is an example of recursive advantages at play.

"You have such a clear dichotomy between [Niantic's] original IP title, Ingress, which was cutting-edge, ahead of its time, incredibly niche. And then you have a simpler, let's say less feature-rich version of that same game paired with the perfect IP, for the first time on mobile in a meaningful way. There's no way that gameplay experience would have fit any other IP better, and I also think there's no way any individual developer could have built a pocket-monster battle game and reached that scale, that quickly."

"We're building one title. It's been two years, it's a $35 million investment. It's a huge investment"

Niantic's success is impressive, of course, but its ties to The Pokemon Company, to Nintendo, and the Pokemon IP itself were decisive. Sheppard offers the mobile version of Lineage 2: Revolution as another example, a game that earned $180 million in a single month when it launched last year. That return required "zero marketing spend" on the part of NCsoft, Sheppard says, the Lineage brand's reputation allowing it to vastly reduce a cost that weighs so heavily on most mobile games.

"And then you look at the broader ecosystem and you have these middle-class developers who are fighting, marginally profitable, just getting the next game out," he adds. "The deck seems really stacked against that."

Gree's rapid ascent was an early indicator of just how lucrative the free-to-play mobile games could be, but the Japanese firm's hold on the market has slipped in the years since. In June 2012, when Gree recorded a $1 billion operating profit after 12 months, Candy Crush Saga was fresh on the market, Clash of Clans was building towards a full launch, and Tencent was just starting to get a feel for the games business. Today, Gree and its International subsidiary are no longer in that top bracket, and while some of the financial resources built up during the boom years remain, the "rich" publishers reinforce and protect their dominance through more than just money.

"We don't have Mario, we don't have Pokemon, we don't have the IP," Sheppard adds, and the persistent emergence of new, mass market platforms over the last decade has ground to a halt. "With no new platform evident, with mobile maturing, with PC, console and web maturing, it's not just a matter of jumping to the new platform any more.

"We're back in the 90s, building console games, and that's all there is, right? In terms of choice of what you can do, it's more limited."

Gree International's sparse release schedule is largely due to the process of defining what, exactly, it can do in the mobile market as it currently stands. Sheppard believes that happiness and success is possible for developers of every size and type, but it's now necessary to be absolutely clear about "what 'good' looks like - not relative to Clash Royale, but relative to what you and your team want to accomplish. You just have to organise accordingly. Trying to be an indie developer in San Francisco just makes no sense. It's insane."

Indeed, San Francisco's reputation as the assumed centre of mobile game development was a key part of Sheppard's talk. It isn't just indie developers who should question the value of maintaining a presence in San Francisco; the city is now so expensive that even a company the size of Gree has to consider the strain it puts on both its resources and its employees. "More expensive than New York, more expensive than London as a place for people to live," Sheppard says. "It puts enormous pressure on the dev teams that we manage in San Francisco, and that goes beyond Gree."

That high cost of living has a negative impact on production, leading to rapid staff turnover as employees struggle to find a satisfying work-life balance. Sheppard knows San Francisco companies with a 50% staff turnover on a single project across a two-year development cycle; making a competitive product is already hard enough, with dealing with that perpetual upheaval. "It's a competitive disadvantage in many ways," he says.

"That was a core part of the restructuring we did in San Francisco. The cost structure didn't make sense. The team wasn't market competitive, although they were all individually amazing people and many of them have gone on to be very successful. Cost of living does eat into our happiness as professionals. It means that your team runs leaner, it means you oftentimes work longer hours, you have to cut corners to get more done in less time. All of those are symptoms of a high cost of living."

"For people who've only worked in mobile or only worked in web, now is the time to go back. Talk to your forebears in console and PC, and learn"

Gree International still has staff in San Francisco, but its total workforce is now distributed across several locations, each with a particular focus. The 40-strong development team is based in Melbourne, Australia, while a Berlin office handles localisation and live operations. The San Francisco team is now purely focused on marketing and product management, because Sheppard believes that America's most expensive city is still the best place in the world to find talent in those disciplines.

That distributed model was inspired by the reaction of console companies to their own maturing market, and Ubisoft in particular. As production costs spiralled, the French publisher was able to hold its own next to larger organisations like Activision and EA by creating AAA games across multiple studios around the world. "Just look at the credits and you'll see ten different locations for that one title," Sheppard said in his talk. "Each of those locations often has a unique area of expertise or specialty, but all work against a cogent vision."

The Ubisoft comparison is certainly apt, because Gree International seems to harbour a similar ambition. Sheppard pointedly refers to his Melbourne development team as "AAA," and it's clear that, even if Gree is part of mobile gaming's "middle-class" right now, it doesn't intend to stay there. Implementing a better cost structure will make the company happier and more secure, but it will also allow more value to be drawn from every dollar invested in its next project - and the next project is a big one.

"We're building one title," he says. "It's been two years, it's a $35 million investment. It's a huge investment, and you need all of your best people on it to even have a shot."

Another company touting single-project investments on that scale was Kabam. Prior to selling the company's Vancouver studio to Netmarble, CEO Kevin Chou told GamesIndustry.biz that it had seven upcoming projects with an average budget (including production and marketing) of almost $25 million each. Chou explained that remaining competitive with the industry's biggest publishers now required investment on that scale. For Sheppard, it's also about seizing the opportunity to join the top-tier of publishers before the gap is too wide to cross. "I do think the window is closing," he says. "I think it's closing hard."

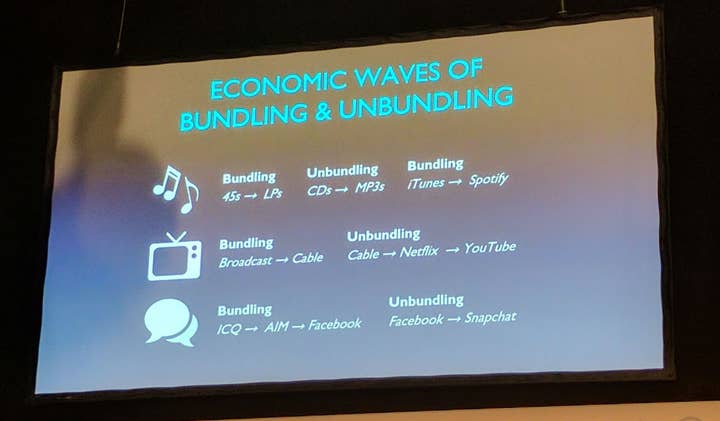

Sheppard is not ready to discuss the fine details of the new game, but he's confident that it will push at the limits of the market for midcore games - in terms of form, and not just investment. To give an idea of the direction Gree was heading, an entire section of his talk was devoted to the Bundling and Unbundling of goods and services as a way of invigorating stagnant marketplaces.

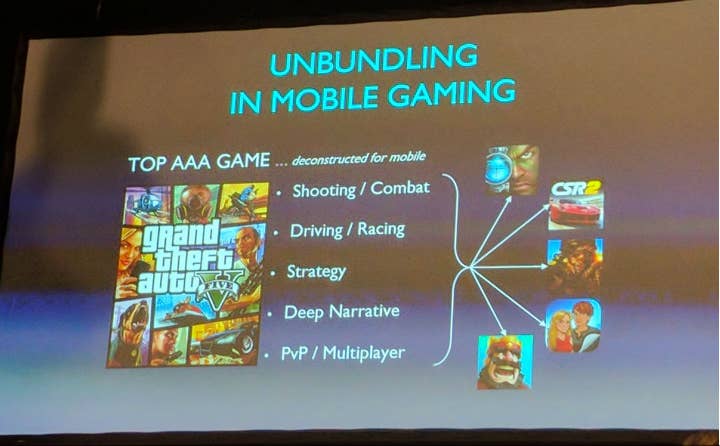

Here, again, console companies pointed a way forward. The same Bundling/Unbundling process was also evident in a landmark game like Grand Theft Auto 3, he said, which gathered gameplay loops that had previously formed the basis of entire franchises into a single, cohesive experience - "like five games in one," Sheppard said. The rise of mobile games following the launch of the iPhone had the opposite effect, resulting in complete products based on solitary gameplay loops.

This is the big opportunity in mobile games now, Sheppard says, and it's what Gree International is aiming for with its new game; not making GTA for smartphones, exactly, but a product that bottles lightning in a similar way to Rockstar all those years ago. "It's super painful, because the fidelity of each loop is so different," Sheppard said in his talk. "At one level it's isometric and at another level it's first-person. We're relying heavily on storytelling to project quality on that universe and make people want to spend time there."

An example of the same idea already exists in the casual market, Sheppard says, in the form of Playrix' Gardenscapes, which combined match-3, simulation and storytelling mechanics to become the breakout original IP in mobile last year. According to data presented by Sheppard, Gardenscapes grew from $30 million and 20 million installs in 2015, to $180 million and 100 million installs last year. The console and PC markets followed the same path, Sheppard said, and it's what the mobile market now demands - "it's a logical response to having 300 apps on your phone."

"I think we're maybe a year ahead of a lot of people in non-casual games," he says. "Playrix is ahead [overall], though, and with the fidelity being lower they can get to market faster. Nobody else is doing this, and they're doing it so well... That's what we aim to do with midcore.

"The market is mature, and the definition of innovation changes with maturity. It's more about synthesis and fidelity. I think that, for people who've only worked in mobile or only worked in web, now is the time to go back. Talk to your forebears in console and PC, and learn."